Abnormal trilobites from the Silurian and Devonian of Europe

RUSSELL D.C. BICKNELL, PATRICK M. SMITH, LISA AMATI, and MELANIE J. HOPKINS

Bicknell, R.D.C., Smith, P.M., Amati, L., and Hopkins, M.J. 2025. Abnormal trilobites from the Silurian and Devonian of Europe. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 70 (2): 205–212.

Malformed trilobites have been documented in deposits ranging from the Cambrian to the Permian. Continued examination of novel malformed specimens provides insight into how trilobites recovered from injuries, experienced genetic abnormalities, and adapted to pathological conditions. This study focuses on trilobites from the Silurian and Devonian of Europe, presenting new records of: (i) a moulting-related injury in Lioharpes venulosus; (ii) genetic malformations in Calymene blumenbachii and Treveropyge sp.; and (iii) a moulting injury or genetic anomaly in Scutellum (Scutellum) pardalios. Additionally, we record evidence of bryozoan growth on a C. blumenbachii specimen. Our findings provide important data for contextualizing the paleobiology of early and middle Paleozoic trilobites, especially related to responses to ecological pressures.

Key words: Trilobita, Calymene, Treveropyge, Lioharpes, Scutellum, evolution, injuries, malformations, teratologies.

Russell D.C. Bicknell [rdcbicknell@gmail.com, rbicknell@amnh.org; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8541-9035 ], Division of Paleontology (Invertebrates), American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, 10024, USA and Palaeoscience Research Centre, School of Environmental & Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia.

Patrick M. Smith [patrick.smith@australian.museum; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4359-8001 ], Palaeontology Department, Australian Museum Research Institute, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia and Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Lisa Amati [lisa.amati@nysed.gov; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9766-7036], Paleontology, New York State Museum, 222 Madison Avenue, Albany, NY 12230, USA.

Melanie J. Hopkins [mhopkins@amnh.org; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3580-2172 ], Division of Paleontology (Invertebrates), American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, 10024, USA.

Received 5 December 2024, accepted 16 February 2025, published online 22 April 2025.

Copyright © 2025 R.D.C. Bicknell et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Trilobites are a morphologically disparate group of marine Paleozoic arthropods that spanned the Cambrian to the end-Permian extinction (Fortey and Owens 1999; Webster 2007; Hughes 2007; Bault et al. 2022). The biomineralised dorsal exoskeleton trilobites exhibited resulted in an exceptional taxonomic record (Lee et al. 2012; Pérez-Huerta et al. 2018; Murdock 2020). These exoskeletons also preserve malformations, providing insight into ecological interactions, developmental anomalies, and evolutionary pressures experienced by the group (Owen 1985; Babcock 1993, 2003, 2007; Pates et al. 2017; De Baets et al. 2022; Bicknell and Kimmig 2023), illustrating how trilobites recovered from injuries, molting issues, genetic malfunctions, or parasites (Šnajdr 1979, 1981; Babcock 1993; Pates et al. 2017; Pates and Bicknell 2019; Bicknell and Smith 2021; Bicknell et al. 2022b; De Baets et al. 2022). Documentation of malformed trilobites therefore enhances our understanding of trilobite paleobiology. To expand the record of malformed specimens and build on synthetic works (see Owen 1985; Babcock 1993, 2003; Bicknell and Smith 2022; Zong et al. 2023), we examined five abnormal trilobites from the Silurian and Devonian of Europe. In doing so, we illustrate evidence for injuries, developmental malformations, and interactions with bryozoans.

Institutional abbreviations.—NHMUK PI, Natural History Museum, Invertebrate Palaeontology Collection, London, UK; NYSM, New York State Museum, Albany, USA.

Material and methods

Trilobite specimens from the NHMUK PI and NYSM were examined for potential malformations.

Photographs of the malformed specimens were taken under LED lighting using an Olympus E-M1 Mark III (NYSM) and a Canon EOS 600D DSLR camera (NHMUK PI). Specimens from the NHMUK PI were photographed without any coating, while NYSM specimens were treated with ammonium chloride to improve the image contrast. Measurements of the specimens were obtained from the photographs using ImageJ software (Schneider et al. 2012).

Terminology.—Malformation: Examples of injuries, pathologies, or teratologies observed in trilobite exoskeletons.

Injury: Exoskeletal breakages that occurred while the organism was alive. Injuries can indicate failed predation attempts, interactions with environmental hazards, or complications during molting (Rudkin 1985; Owen 1985; Babcock 1993; Fatka et al. 2015; Bicknell et al. 2018; Bicknell and Pates 2020). Notably, injuries are usually localized, while extensive breakages typically reflect post-mortem compaction processes (Leighton 2011). Larger injuries have L-, U-, V-, or W-shapes (Babcock 1993; Bicknell et al. 2022a, 2023b), whereas smaller indentations are typically single spine injuries (SSI) (Pates and Bicknell 2019; Bicknell and Pates 2020). Additionally, evidence of cicatrization and repair is frequently present, although this varies based on the extent of exoskeletal recovery (Rudkin 1979; Owen 1985; Babcock 2007; Bicknell and Paterson 2018).

Teratology: Observable external manifestations of developmental, embryological, or genetic disturbances in the exoskeleton (Šnajdr 1981; Owen 1985). Although rare, teratological features may coincide with injuries (Owen 1985; Bicknell et al. 2024a, b). These malformations can include the addition or loss of nodes, segments, or spines, as well as irregular rib and furrow shapes (Owen 1985; Bicknell and Smith 2021, 2022).

Pathology: Malformed exoskeletal regions that reflect parasitic activity or infections. Such structures typically present as circular or oval swellings (Šnajdr 1978; Owen 1985; De Baets et al. 2022).

Results

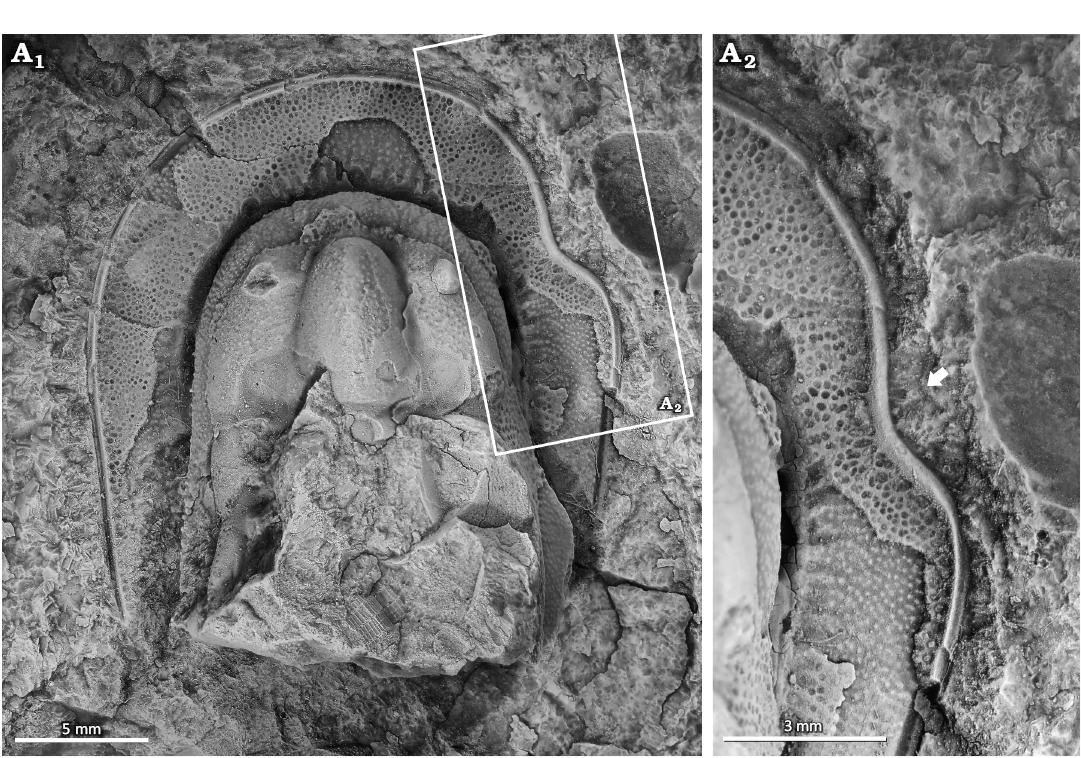

Lioharpes venulosus (Hawle & Corda, 1847); NYSM 19739. Koněprusy Limestone, Pragian, Lower Devonian, Koněprusy, Czech Republic (Fig. 1).

NYSM 19739 is an isolated cephalon that is 26.2 mm long and 22.3 mm wide with a malformation consisting of disrupted and irregular pygidial ribs on the right side (Fig. 1A2). The malformation is a U-shaped indentation in the marginal rim. The indentation is 5.6 mm long and extends 1.9 mm towards the midline. Fringe pits proximal to indentation are irregular, ovate, and occasionally fused into larger pits.

Fig. 1. Malformed harpetid trilobite Lioharpes venulosus (Hawle & Corda, 1847), NYSM 19739 from the Koněprusy Limestone, Pragian, Lower Devonian, Koněprusy, Czech Republic. A1, complete cephalon; A2, close up showing U-shaped indentation (arrow). Specimen coated in ammonium chloride sublimate.

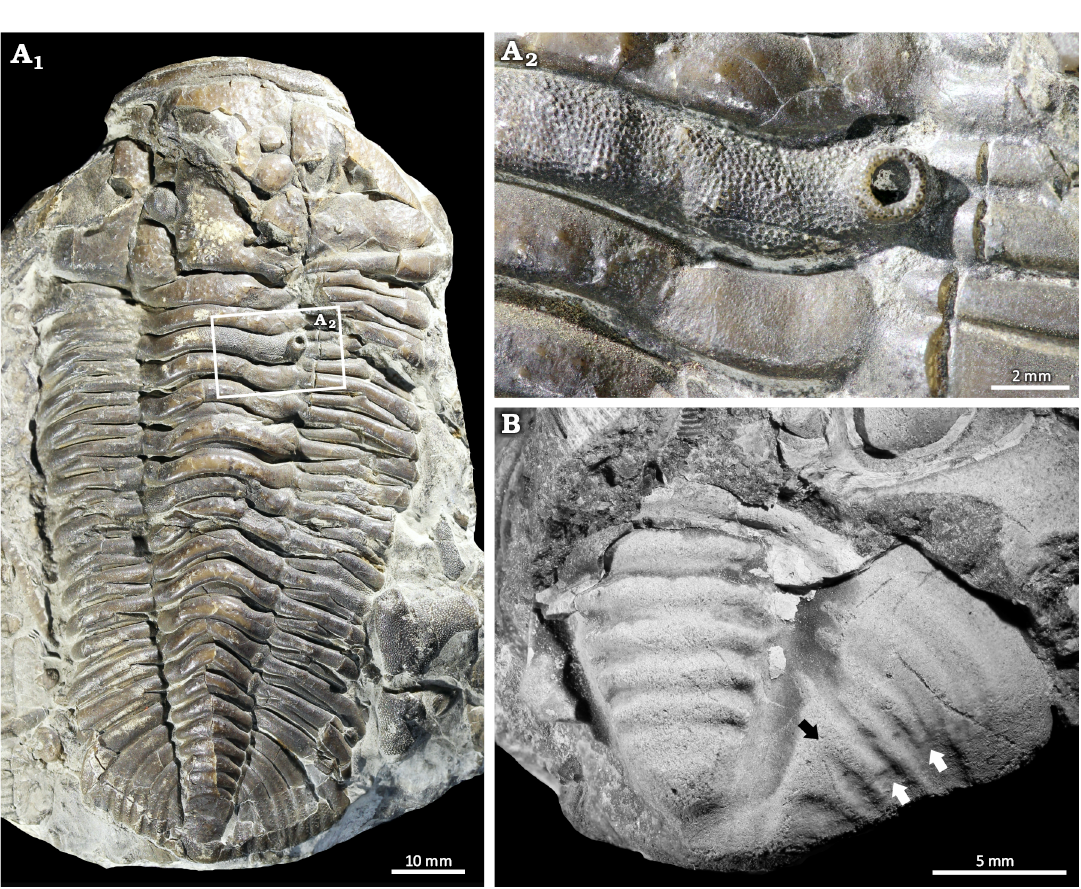

Calymene blumenbachii Brongniart in Desmarest, 1817; NHMUK PI In 19857; NHMUK PI In 65061. Much Wenlock Limestone Formation, Wenlock, Homerian Silurian, England, UK (Fig. 2).

NHMUK PI In 65061 is an articulated Calymene blumenbachii specimen showing a partial cephalon, thorax, and pygidium. The specimen is 92.9 mm long and 48.6 mm wide across the cephalon (Fig. 2A1). The specimen has a structure on the second thoracic axial ring that is an elevated, hollow, rounded crater, 1.7 mm in diameter and is covered with closely spaced pits or openings (Fig. 2A2). The exoskeleton around the crater is not deformed and the pattern of closely-spaced openings continues across the axial ring.

NHMUK PI In 19857 is an isolated, partial pygidium that is 13.2 mm long and 18.2 mm wide with a malformation on the right side (Fig. 2B). Disrupted and irregular pygidial ribs are observed in this area. Two ribs terminate 1.6 mm from the pygidial margin (Fig. 2B) and two other ribs are fused 1.2 mm from the pygidial axis (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Abnormal calymenid trilobites Calymene blumenbachii Brongniart in Desmarest, 1817 from the Much Wenlock Limestone Formation, Homerian, Wenlock, Silurian, England, UK. A. NHMUK PI In 65061. A1, complete specimen; A2, close up showing the large bryozoan growth. B. NHMUK PI In 19857 showing pygidial ribs that terminate early (white arrows) and are fused proximal to the medial lobe (black arrow).

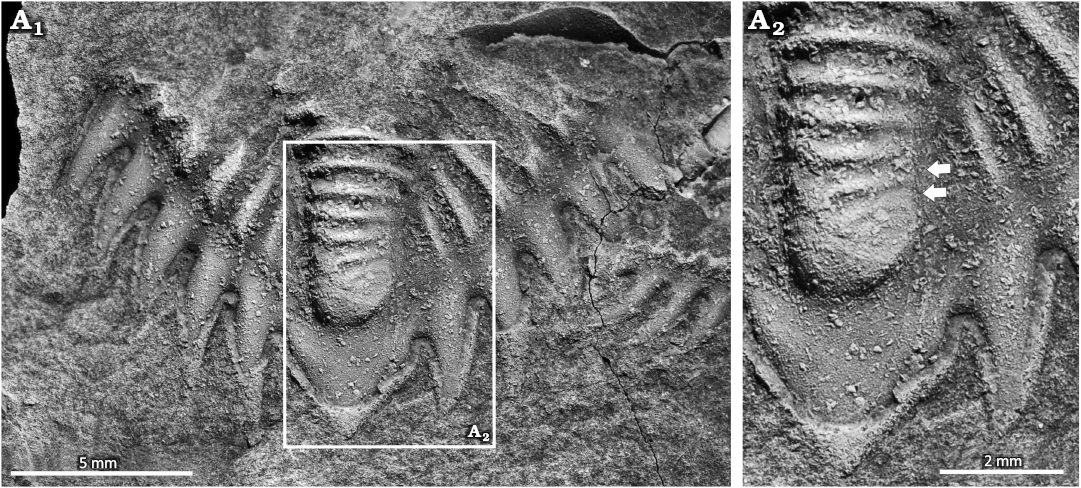

Treveropyge sp., NYSM 19740. Saint Céneré Formation, Lochkovian, Lower Devonian, Mayenne, France (Fig. 3).

NYSM 19740 is an isolated pygidium that is 11.6 mm long and 17.9 mm wide (Fig. 3A1). The specimen has an asymmetrical axial lobe (Fig. 3A2). Two axial rings are malformed, slightly curved to the right and extend across ~60% the axial lobe.

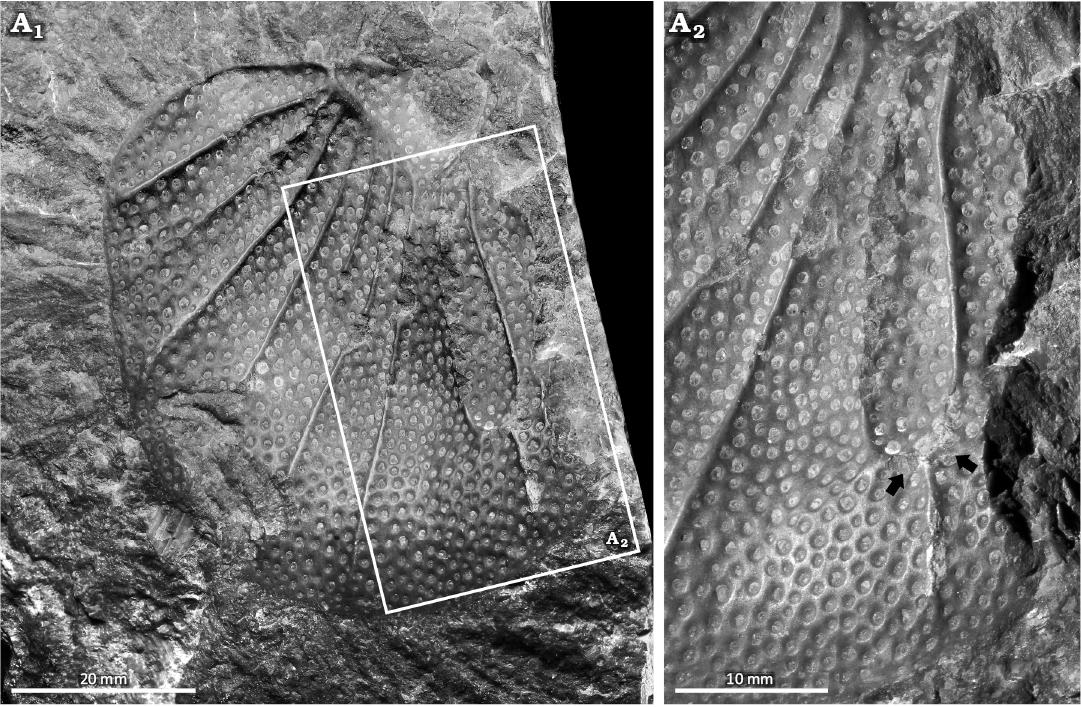

Scutellum (Scutellum) pardalios (Whidborne, 1889), NHMUK PI I 1108. Barton Limestone Member, Torquay Limestone Formation, Givetian, Middle Devonian, England, UK (Fig. 4).

NHMUK PI I 1108 is an isolated, partial pygidium preserved as an external impression that is 59.5 mm long and 44.0 mm wide (Fig. 4). The specimen has a malformation on the right side (left side in life) (Fig. 4A2). The specimen shows fusion of two pygidial ribs into a singular rib. Fusion occurs 29.1 mm from the pygidial axis (Fig. 4A2). The fused rib terminates 4.8 mm from the pygidial margin.

Fig. 3. Malformed acastid trilobite Treveropyge sp., NYSM 19740 from the Saint Céneré Formation, Lockkovian, Lower Devonian, Mayenne, France. A1, complete pygidium; A2, close up showing asymmetrical axial lobe and incomplete axial ring (arrows). Specimen coated in ammonium chloride sublimate.

Fig. 4. Malformed styginid trilobite Scutellum (Scutellum) pardalios (Whidborne, 1889), NHMUK PI I 1108 from the Barton Limestone Member, Torquay Limestone Formation, Givetian, Middle Devonian, England, UK. A1, pygidium preserved as external impression; A2, close up showing fused pygidial pleurae (arrows).

Discussion

Examining the specimens presented herein revealed evidence of exoskeletal injuries and morphologies indicative of genetic anomalies. Furthermore, one specimen shows signs of epibiont interactions. We explore each group of abnormalities separately and propose possible explanations for the observed morphologies.

Injuries.—The examined Lioharpes venulosus has a U-shaped indentation along the cephalic fringe. This morphology is comparable to malformations in other harpetid trilobites assigned to injuries (see Warburg 1925; Sinclair 1947; Prantl and Přibyl 1954; Šnajdr 1979; Owen 1983, 1985; Přibyl and Vaněk 1986). We, therefore, propose that this malformation is an injury, expanding the record of injured L. venulosus (Prantl and Přibyl 1954; Přibyl and Vaněk 1986). Determining the injury origin is complicated as injured harpetid cephala have been attributed to moulting complications (Owen 1983), failed predation (Šnajdr 1979; Owen 1983), and unknown origins (Fatka et al. 2022). The large cephalic region is commonly considered to have been damaged during moulting, as the soft-shelled exoskeleton was prone to tearing (Owen 1983, 1985). We align with this proposal, suggesting that the injury records a complicated moulting event.

The fringe pits along the injury margin are deformed and show possible fusion. This recovery system broadly reflects the pattern proposed for trinucleid trilobites (Šnajdr 1979; Owen 1985), indicating similar exoskeletal growth pathways. However, the Owen (1985) trinucleid model did not illustrate larger pits or pit fusion, highlighting subtle differences between trinucleid and harpetid recovery, despite their parallel evolutionary adaptations (Beech et al. 2024).

Injuries that remove sections of the cephalic fringe could significantly affect the functionality of the individual (Owen 1985; Babcock 1993; Bicknell et al. 2018). Harpetid fringes likely served multiple functions (Pates and Drage 2024; Beech et al. 2024) including filtering for food (Fortey and Owens 1999), sensory roles (Schoenemann 2021), sediment ploughing (Staff and Reek 1911; Ebach and McNamara 2002), hydrostatic support (Richter 1920), cephalic reinforcement (Miller 1972; Ebach and McNamara 2002), burrowing (Pates and Drage 2024), and enhancing hydrodynamic efficiency (Pates and Drage 2024). Regardless of the primary function, a cephalic injury would have been detrimental. We, therefore, propose that the cephalon would recover relatively quickly over subsequent moulting events (Owen 1985), as more critical exoskeletal regions receive priority in regeneration (Zong and Bicknell 2022; Bicknell and Cuomo 2024).

Teratologies.—Teratological malformations in trilobites often reflect the addition, reduction, or deformation of spines, furrows, ribs, tergites, and nodes (Owen 1985; Babcock 1993, 2007; Bicknell et al. 2023a). In the examined specimens, teratologies in Calymene blumenbachii, Scutellum (Scutellum) pardalios, and Treveropyge sp. pygidia were documented. These reflect asymmetry, abnormal axial rings, and fusion of pygidial ribs, common examples of teratologies in the trilobite fossil record (see Šnajdr 1958, 1981; Přibyl and Vaněk 1973; Strusz 1980; Owen 1985; Budil et al. 2010; Nielsen and Nielsen 2017; Zong 2021).

The isolated Calymene blumenbachii pygidium shows irregular and fused ribs. This is comparable to malformed specimens of Dalmanities pleuroptyx (Green, 1832) (Bicknell et al. 2024a: fig. 12), Dechenella macrocephalus (Hall, 1859) (Rudkin 1985: fig. 2), Niobina sp. (Tjernvik 1956: pl. 5: 17), and Prionopeltis archiaci (Barrande, 1846) (Šnajdr 1981: pl. 5: 4), all of which exhibit significant rib disruption. Larger teratologies with comparable morphologies are attributed to major developmental malfunctions (Rudkin 1985). As the teratology is limited to the pleural region, this was likely a genetic or developmental issue that was not detrimental to the individual (Owen 1985).

The Treveropyge sp. pygidium has an asymmetrical axial lobe with two malformed axial rings. These morphologies are similar to malformed Calliops marginatus Tripp, 1962 (Tripp 1962: pl. 28: 16), Dolicholeptus licticallis Öpik, 1982 (Bicknell et al. 2023b: fig. 2E), and Sceptaspis lincolnensis (Branson, 1909) (Rudkin 1985: fig. 1E–G). These minor malformations have been attributed to genetic malfunctions (Owen 1985; Bicknell et al. 2024a), particularly incomplete development (Rudkin 1985), or non-functional somites (Nielsen and Nielsen 2017). We propose that a genetic malfunction occurred for NYSM 19740. As the malformed region is not proximal to vital organs, this teratology would not have impacted the individual (Nielsen and Nielsen 2017).

Scutellum (Scutellum) pardalios (Fig. 4) shows evidence of two pygidial ribs fusing into one rib distally. As there are no exoskeletal regions devoid of ornamentation, a condition expected of failed predation in styginids (Šnajdr 1990a, b; Holloway 1996), we exclude this option here. Most other malformed styginids reflect molting complications resulting in abnormal recovery (Šnajdr 1960, 1990b; Erben 1967), genetic malfunctions (Holloway 1996), or parasitic infestation during earlier developmental stages (Šnajdr 1990a, b). A review of the literature highlighted only one other malformed styginid with distal fusion of two ribs, Bojoscutellum obsoletum (Šnajdr, 1960) (Šnajdr 1990b: fig. 2), and this is attributed to parasitism (Šnajdr 1990b). As there is no evidence for parasitism, we propose that NHMUK PI I 1108 may have experienced a complicated moult due to its macropygous pygidium (see Šnajdr 1960, 1990b; Erben 1967), or had a genetic malfunction during early development, either of which may have resulted in fused ribs. Determining the impact of the malformation on the individual is complex. However, as the disruption is minor, it likely would not have led to significant functional impairment of the pygidial region.

Epibionts.—Trilobite exoskeletons with encrusting animals are important examples of organismal interactions (see Prokop 1965; Morris and Rollins 1971; Sprinkle 1973; Kesling and Chilman 1975; Brandt 1996; Taylor and Brett 1996; Kacha and Šarič 2009; Key et al. 2010; Vinn et al. 2017). Within the trilobites examined here, we report one Calymene blumenbachii specimen (NHMUK PI In 65061, Fig. 2) with epibionts resembling those on Flexicalymene Shirley, 1936 (Brandt 1996: figs. 1.4, 1.6). This is an encrusting trepostome bryozoan forming a low mat with an ovate zoarium preserved on the 3rd thoracic tergite. The restricted encrustation region within the area bounded by articulating sclerite margins suggests that the encrustation occurred while the animal was alive (see Brandt 1996; Key et al. 2010).

Conclusions

Novel records of trilobite abnormalities are explored herein using Silurian and Devonian species. In doing so, we demonstrate additional examples of injuries, teratologies and possible bryozoan interactions. This presents further insight into trilobite paleoecology and sheds more light on how trilobites recovered from such conditions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Richard Howard (NHMUK PI) for help with collections. We thank also Oldřich Fatka (Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) and Olev Vinn (University of Tartu, Estonia) for constructive reviews of the manuscript. This research was funded by an Australian Research Council grant (FT120100770) a University of New England Postdoctoral Fellowship (to RDCB), and an MAT Program Postdoctoral Fellowship (to RDCB).

Editor: Krzysztof Hryniewicz.

References

Babcock, L.E. 1993. Trilobite malformations and the fossil record of behavioral asymmetry. Journal of Paleontology 67: 217–229. Crossref

Babcock, L.E. 2003. Trilobites in Paleozoic predator-prey systems, and their role in reorganization of early Paleozoic ecosystems. In: P. Kelley, M. Kowalewski, and T.A. Hansen (eds.), Predator-Prey interactions in the Fossil Record, 55–92. Springer, New York. Crossref

Babcock, L.E. 2007. Role of malformations in elucidating trilobite paleobiology: a historical synthesis. In: D.G. Mikulic, E. Landing, and J. Kluessendorf (eds.), Fabulous Fossils—300 Years of Worldwide Research on Trilobites, 3–19. University of the State of New York, State Education Dept., New York State Museum, New York.

Barrande, J. 1846. Notice Préliminaire sur le systême Silurien et les Trilobites de Bohême. 96 pp. Hirschfeld, Leipzig. Crossref

Bault, V., Balseiro, D., Monnet, C., and Crônier, C. 2022. Post-Ordovician trilobite diversity and evolutionary faunas. Earth-Science Reviews 230: 104035. Crossref

Beech, J.D., Bottjer, D.J., and Smith, N.D.2024. Parallel evolution of unusual ‘harpiform’ morphologies in distantly related trilobites. Journal of Paleontology 98: 732–743. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C. and Cuomo, C. 2024. On the recovery of malformed horseshoe crabs across multiple molting stages. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 65: 317–326. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C. and Kimmig, J. 2023. Clustered and injured Pseudogygites latimarginatus from the Late Ordovician Lindsay Formation, Canada. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 309: 199–208. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C. and Paterson, J.R. 2018. Reappraising the early evidence of durophagy and drilling predation in the fossil record: implications for escalation and the Cambrian Explosion. Biological Reviews 93: 754–784. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C. and Smith, P.M. 2021. Teratological trilobites from the Silurian (Wenlock and Ludlow) of Australia. The Science of Nature 108: 25. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C. and Smith, P.M. 2022. Examining abnormal Silurian trilobites from the Llandovery of Australia. PeerJ 10: e14308. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C. and Pates, S. 2020. Exploring abnormal Cambrian-aged trilobites in the Smithsonian collection. PeerJ 8: e8453. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Holmes, J.D., García-Bellido, D.C., and Paterson, J.R. 2023a. Malformed individuals of the trilobite Estaingia bilobata from the Cambrian Emu Bay Shale and their palaeobiological implications. Geological Magazine 160: 803–812. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Holmes, J.D., Pates, S., García-Bellido, D.C., and Paterson, J.R. 2022a. Cambrian carnage: Trilobite predator-prey interactions in the Emu Bay Shale of South Australia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 591: 110877. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Pates, S., and Botton, M.L. 2018. Abnormal xiphosurids, with possible application to Cambrian trilobites. Palaeontologia Electronica 21 (2): 1–17. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Smith, P.M., and Hopkins, M.J. 2024a. An atlas of malformed trilobites from North American repositories Part 2. The American Museum of Natural History. American Museum Novitates 2024 (4027): 1–36. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Smith, P.M., and Miller-Camp, J. 2024b. An atlas of malformed trilobites from North American repositories Part 1. The Indiana University Paleontological Collection. American Museum Novitates 2024 (4026): 1–16. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Smith, P.M., and Paterson, J.R. 2023b. Malformed trilobites from the Cambrian, Ordovician, and Silurian of Australia. PeerJ 11: e16634. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Smith, P.M., Bruthansová, J., and Holland, B. 2022b. Malformed trilobites from the Ordovician and Devonian. PalZ 96: 1–10. Crossref

Brandt, D.S. 1996. Epizoans on Flexicalymene (Trilobita) and implications for trilobite paleoecology. Journal of Paleontology 70: 442–449. Crossref

Branson, E.B. 1909. The fauna of the Residuary Auburn Chert of Lincoln County, Missouri. Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis 18: 39–52.

Budil, P., Fatka, O., Zwanzig, M., and Rak, Š. 2010. Two unique Middle Ordovician trilobites from the Prague Basin, Czech Republic. Journal of the National Museum (Prague), Natural History Series 179: 95–104.

De Baets, K., Budil, P., Fatka, O., and Geyer, G. 2022. Trilobites as hosts for parasites: From paleopathologies to etiologies. In: K. De Baets and J.W. Huntley (eds.), The Evolution and Fossil Record of Parasitism: Coevolution and Paleoparasitological Techniques, 173–201. Springer International Publishing, Cham. Crossref

Desmarest, A.-G. 1817. Crustacés fossiles, in Société de Naturalistes et d’Agriculteurs, Nouveau Dictionnaire d’Histoire naturelle, appliquée aux Arts, à l’Agriculture, à l’Économie rurale et domestique, à la Médecine, etc. 17 pp. Deterville, Paris.

Ebach, M.C. and McNamara, K.J. 2002. A systematic revision of the family Harpetidae (Trilobita). Records of the Western Australian Museum 21: 235–268. Crossref

Erben, H.K. 1967. Bau der Segmente und der Randbestachelung im Pygidium der Scutelluidae, Tril. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 129: 1–64.

Fatka, O., Budil, P., and Grigar, L. 2015. A unique case of healed injury in a Cambrian trilobite. Annales de Paléontologie 101: 295–299. Crossref

Fatka, O., Budil, P., and Mikuláš, R. 2022. Healed injury in a nektobenthic trilobite: “Octopus-like” predatory style in Middle Ordovician? Geologia Croatica 75: 189–198. Crossref

Fortey, R.A. and Owens, R.M. 1999. Feeding habits in trilobites. Palaeontology 42: 429–465. Crossref

Green, J. 1832. A Monograph of the Trilobites of North America: With Coloured Models of the Species. 87 pp. J. Brano, Philadelphia. Crossref

Hall, J. 1859. Natural History of New York, Paleontology III. 532 pp. New York State Museum, New York.

Hawle, I. and Corda, A.J. 1847. Prodrom einer monographie der böhmischen Trilobiten. Abhandlungen Koeniglichen Boehmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften. 200 pp. J.G. Clave, Prague.

Holloway, D.J. 1996. New Early Devonian styginid trilobites from Victoria, Australia, with revision of some spinose styginids. Journal of Paleontology 70: 428–438. Crossref

Hughes, N.C. 2007. The evolution of trilobite body patterning. Annual Reviews in Earth and Planetary Sciences 35: 401–434. Crossref

Kacha, P. and Šarič, R. 2009. Host preferences in Late Ordovician (Sandbian) epibenthic bryozoans: example from the Zahořany Formation of Prague Basin. Bulletin of Geosciences 84: 169–178. Crossref

Kesling, R.V. and Chilman, R.B. 1975. Strata and megafossils of the Middle Devonian Silica Formation. University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology 8: 1–408.

Key, M.M., Schumacher, G.A., Babcock, L.E., Frey, R.C., Heimbrock, W.P., Felton, S.H., Cooper, D.L., Gibson, W.B., Scheid, D.G., and Schumacher, S.A. 2010. Paleoecology of commensal epizoans fouling Flexicalymene (Trilobita) from the Upper Ordovician, Cincinnati Arch region, USA. Journal of Paleontology 84: 1121–1134. Crossref

Lee, M.R., Torney, C., and Owen, A.W. 2012. Biomineralisation in the Palaeozoic oceans: evidence for simultaneous crystallisation of high and low magnesium calcite by phacopine trilobites. Chemical Geology 314: 33–44. Crossref

Leighton, L.R. 2011. Analyzing predation from the dawn of the Phanerozoic. In: M. Laflamme, J.D. Schiffbauer, and S.Q. Dornbos (eds.), Quantifying the Evolution of Early Life, 73–109. Springer, Dordrecht. Crossref

Miller, J. 1972. Aspects of the Biology and Palaeoecology of Trilobites. 201 pp. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester.

Morris, R.W. and Rollins, H.B. 1971. The distribution and paleoecological interpretation of Cornulites in the Waynesville Formation (Upper Ordovician) of southwestern Ohio. The Ohio Journal of Science 71: 159–170.

Murdock, D.J.E. 2020. The ‘biomineralization toolkit’ and the origin of animal skeletons. Biological Reviews 95: 1372–1392. Crossref

Nielsen, M.L. and Nielsen, A.T. 2017. Two abnormal pygidia of the trilobite Toxochasmops from the Upper Ordovician of the Oslo Region, Norway. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 65: 171–175. Crossref

Öpik, A.A. 1982. Dolichometopid trilobites of Queensland, Northern Territory, and New South Wales. Bulletin of the Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology & Geophysics 175: 1–85.

Owen, A.W. 1983. Abnormal cephalic fringes in the Trinucleidae and Harpetidae (Trilobita). Special Papers in Paleontology 30: 241–247.

Owen, A.W. 1985. Trilobite abnormalities. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences 76: 255–272. Crossref

Pates, S. and Bicknell, R.D.C. 2019. Elongated thoracic spines as potential predatory deterrents in olenelline trilobites from the lower Cambrian of Nevada. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 516: 295–306. Crossref

Pates, S. and Drage, H.B. 2024. Hydrodynamic function of genal prolongations in trinucleimorph trilobites revealed by computational fluid dynamics. bioRxiv: 2024.01.26.577348. Crossref

Pates, S., Bicknell, R.D.C., Daley, A.C., and Zamora, S. 2017. Quantitative analysis of repaired and unrepaired damage to trilobites from the Cambrian (Stage 4, Drumian) Iberian Chains, NE Spain. Palaios 32: 750–761. Crossref

Pérez-Huerta, A., Coronado, I., and Hegna, T.A. 2018. Understanding biomineralization in the fossil record. Earth-Science Reviews 179: 95–122. Crossref

Prantl, F. and Přibyl, A. 1954. O českých zástupcích čeledi Harpedidae (Hawle et Corda). Rozpravy Státního Geologického ústavu Československé Republiky 18: 1–170.

Přibyl, A. and Vaněk, J. 1973. Zur Taxonomie und Biostratigraphie der crotalocephaliden Trilobiten aus dem böhmischen Silur und Devon. Sbornik Narodniho muzea v Praze. Rada C, Literarni historie 28: 37–92.

Přibyl, A. and Vaněk, J. 1986. A study of morphology and phylogeny of the family Harpetidae Hawle and Corda, 1847 (Trilobita). Sborník Národního Muzea v Praze, řada B 42: 1–72.

Prokop, R. 1965. Argodiscus hornyi gen. n. et sp. n. (Edrioasteroidea) from the Middle Ordovician of Bohemia and a contribution to the ecology of the edrioasteroids. Časopis Národního muzea 134: 30–32.

Richter, R. 1920. Beiträge zur Kenntnis devonischer Trilobiten: 3. Über die Organisation von Harpes, einen Sonderfall unter Crustaceen. Sonderabdruck aus dem Abhandlungen der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 31: 1–218.

Rudkin, D.M. 1979. Healed injuries in Ogygopsis klotzi (Trilobita) from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia. Royal Ontario Museum, Life Sciences Occasional Paper 32: 1–8.

Rudkin, D.M. 1985. Exoskeletal abnormalities in four trilobites. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 22: 479–483. Crossref

Schneider, C.A., Rasband, W.S., and Eliceiri, K.W. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9: 671–675. Crossref

Schoenemann, B. 2021. An overview on trilobite eyes and their functioning. Arthropod Structure & Development 61: 101032. Crossref

Shirley, J. 1936. Some British trilobites of the family Calymenidae. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 92: 384–422. Crossref

Sinclair, G.W. 1947. Two examples of injury in Ordovician trilobites. American Journal of Science 245: 250–257. Crossref

Šnajdr, M. 1958. Trilobiti českého středního kambria. Rozpravy Ustrĕdního ústavu geologického 24: 1–280.

Šnajdr, M. 1960. Studie o Celedi Scutelluidae (Trilobitae). Rozpravy Ustrĕdního ústavu geologického 26: 11–221.

Šnajdr, M. 1978. Pathological neoplasms in the fringe of Bohemoharpes (Trilobita). Věstník Ústředního ústavu geologického 53: 49–50.

Šnajdr, M. 1979. Two trinucleid trilobites with repair of traumatic injury. Věstník Ústředního ústavu geologického 54: 49–50.

Šnajdr, M. 1981. Bohemian Proetidae with malformed exoskeletons (Trilobita). Sborník geologických věd, Paleontologie 24: 37–61.

Šnajdr, M. 1990a. Bohemian Trilobites. 265 pp. Geological Survey, Prague.

Šnajdr, M. 1990b. Five extremely malformed scutelluid pygidia (Styginidae, Trilobita). Věstník Ústředního ústavu geologického 65: 115–118.

Sprinkle, J. 1973. Morphology and Evolution of Blastozoan Echinoderms. 284 pp. Museum of Compariaitve Zoology, Harvard University, Boston. Crossref

Staff, H. and Reek, H. 1911. Über die Lebensweise der Trilobiten. Eine entwicklung mechanische Studie. Sitzungsberichte die Gesellschaft naturforschender Fruende zu Berlin 2: 130–146.

Strusz, D.L. 1980. The Encrinuridae and related trilobite families, with a description of Silurian species from southeastern Australia. Palaeontographica Abteilung A 168: 1–68.

Taylor, W.L. and Brett, C.E. 1996. Taphonomy and paleoecology of echinoderm Lagerstätten from the Silurian (Wenlockian) Rochester Shale. Palaios 11: 118–140. Crossref

Tjernvik, T.E. 1956. On the early Ordovician of Sweden: stratigraphy and fauna. Bulletin of the Geological Institution of the University of Uppsala 36: 107–284.

Tripp, R.P. 1962. Trilobites from the confinis Flags (Ordovician) of the Girvan District, Ayrshire. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 65 (1): 1–40. Crossref

Vinn, O., Toom, U., and Isakar, M. 2017. The earliest cornulitid on the internal surface of the illaenid pygidium from the Middle Ordovician of Estonia. Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences 66: 193–197. Crossref

Warburg, E. 1925. The Trilobites of the Leptaena Limestone in Dalarne: With a Discussion of the Zoological Position and the Classification of the Trilobita. 446 pp. Almqvist & Wiksells boktryckeri-a.-b., Uppsala.

Webster, M. 2007. A Cambrian peak in morphological variation within trilobite species. Science 317: 499–502. Crossref

Zong, R.-W. 2021. Abnormalities in early Paleozoic trilobites from central and eastern China. Palaeoworld 30: 430–439. Crossref

Zong, R.-W. and Bicknell, R.D.C. 2022. A new bilaterally injured trilobite presents insight into attack patterns of Cambrian predators. PeerJ 10: e14185. Crossref

Zong, R.-W., Fan, R., and Gong, Y. 2023. Predation bias of Ordovician predators on trilobites. Journal of the Geological Society 180: jgs2023–019. Crossref

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (2): 205–212, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01229.2024