A diminutive pterosaur from the uppermost Maastrichtian chalk of Denmark

JESPER MILÀN, STEN LENNART JAKOBSEN, and BENT ERIK KRAMER LINDOW

Milàn, J., Jakobsen, S.L., and Lindow, B.E.K. 2025. A diminutive pterosaur from the uppermost Maastrictian chalk of Denmark. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 70 (4): 723–730.

A fragment of pterosaur finger bone was found in the chalk in the uppermost Maastrichtian, Højerup Member of the Møns Klint Formation strata of Holtug quarry at the UNESCO World Heritage site Stevns Klint. This represents the first record of this group from the chalk of Denmark. The specimen is identified a fragment of a left proximal phalanx 1 of digit IV by comparison with similar elements showing the overall three-pronged expression of the posterior, ventral and olecranon processes. The dimensions of the specimen shows that small-bodied pterosaurs with a wingspan of less than 50 cm persisted through to the last 50 000–60 000 years of the Cretaceous. It overlaps in size with contemporaneous birds, rejecting previous hypotheses that Late Cretaceous pterosaurs and birds avoided competition through size-based niche partitioning.

Key words: Pterosauria, Denmark, Maastrichtian, Cretaceous, Stevns Klint.

Jesper Milàn [jesperm@oesm.dk; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9556-3177 ], Sten Lennart Jakobsen [stenlennart@yahoo.dk; ORCID: https//orcid.org/0009-0004-3040-7810 ], and Bent Erik Kramer Lindow [cetotherium@hotmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1864-4221 ], KALK/Museums of East Zealand, Rådhusvej 2, 4640 Faxe, Denmark.

Received 3 March 2025, accepted 5 November 2025, published online 10 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 J. Milàn et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Pterosaurs were flying vertebrates which originated in the Triassic, diversified considerably in size and shape throughout the Mesozoic, and achieved a global distribution. They went extinct at the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) boundary. By the Maastrichtian, fossils so far indicate that pterosaur diversity consisted exclusively of large- to extremely large-bodied taxa with wingspans above 2 m and up to 11 m (Martill and Smith 2024), although remains of taxa with estimated wingspans slightly below 2 m are rare, but not absent from the Late Cretaceous record (Martin-Silverstone et al. 2016; Longrich et al. 2018). Earlier hypotheses suggesting decreases in pterosaur diversity or even extinction during the Cretaceous through ecological competition with birds are now considered invalid (McGowan and Dyke 2007; Dyke et al. 2009; Martill and Smith 2024). However, the absence of fossil remains of pterosaurs with wingspans below 2 m, as well as birds above this size, during the Late Cretaceous, is still hypothesized to be the result of size-based niche partitioning between the two groups to avoid direct ecological competition (Longrich et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2023), although this is likely the result of general preservational bias against any small pterosaurs during the epoch (Martin-Silverstone et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2022).

This paper describes a new pterosaur specimen from the uppermost Maastrichtian of Denmark. It represents one of the smallest Maastrichtian pterosaurs worldwide, and may provide insights into niche partitioning with end-Cretaceous birds.

Institutional abbreviations.—FSAC-OB, Faculté des Sciences Aïn Chock, Casablanca, Morocco; OESM, KALK/Museums of East Zealand, Denmark.

Material and methods

The present study concerns three small bone fragment recovered by one of the authors (SLJ), while sampling micro ammonite aptychi. The fragment was found in a 5 kg sample of topmost Maastrichtian chalk from the Højerup Member at Holtug Quarry, Stevns Klint (Fig. 1). The sample was treated using the traditional Glauber’s Salt method for breaking up weakly cemented sediment samples such as white chalk (Surlyk 1972; Gravesen and Jakobsen 2013). Initially, the chalk was completely dried out in an oven at a temperature of 150°C for a couple of hours, subsequently followed by boiling in a supersaturated Glauber’s Salt solution (Na2SO4·10H2O, hydrated sodium sulphate). After the sediment had disintegrated and washed, the residue was sieved into fractions of 2 and 1 mm, and fossils were picked from the fractions under binocular microscope. During this process the first bone fragment was recovered together with 28 additional smaller, indeterminate bone fragments. The fragments were subject to ultrasonic cleaning to remove adherent chalk obscuring as details of the surface. Photographs were made with a Microeye Discovery digital microscope. The specimens are stored in the collection of Geomuseum Faxe/Østsjællands Museum, collection no. OESM 13096, 13323, and 13324. Six of the smaller pieces are numbered OESM 13320–13322, OESM 13325–13327.

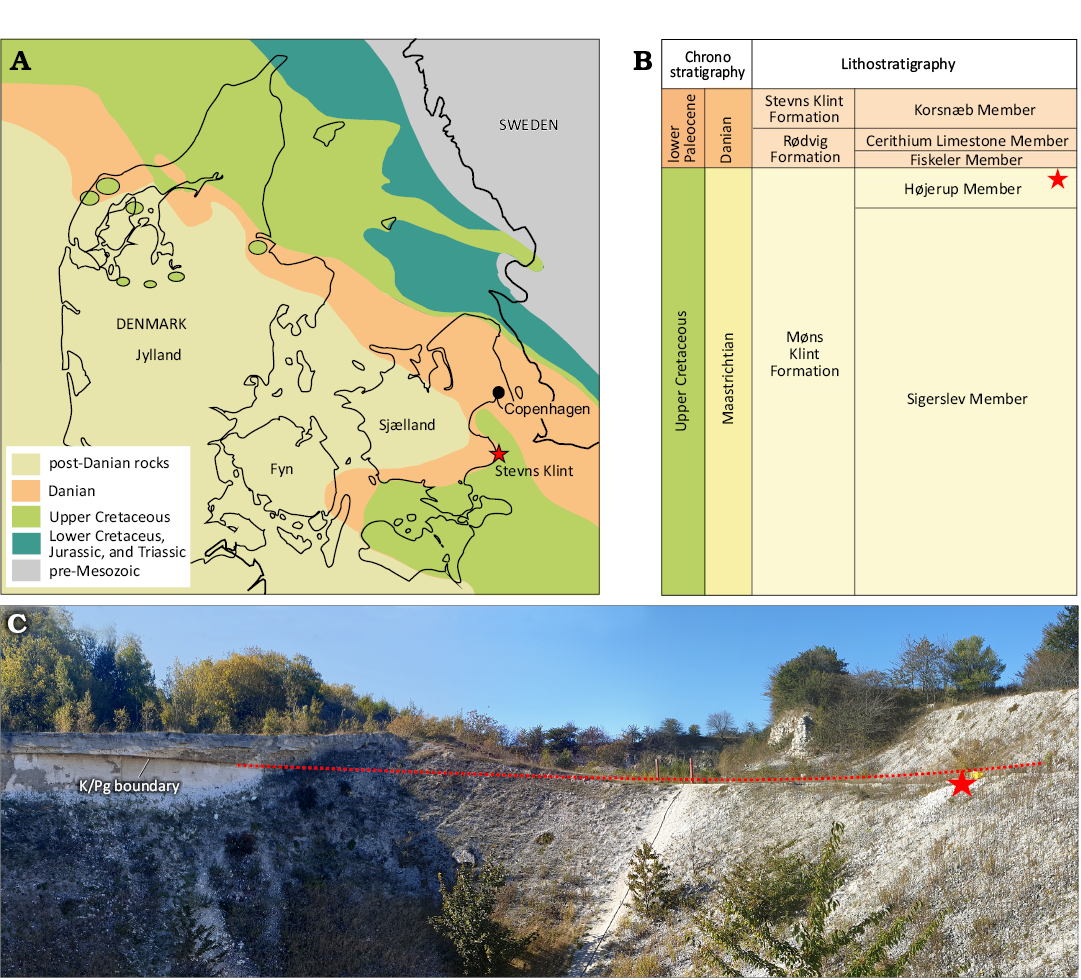

Fig. 1. Study area. A. Pre-Quaternary map of Denmark, modified from Thomsen (1995). The pterosaur bone fragments OESM 13096, 13323 and 13324, were found in the now abandoned Holtug limestone quarry at Stevns Klint, Denmark (55.341957N, 12.446692E). B. Schematic representation of the Maastrichtian–lower Danian stratigraphy of Denmark, modified from Lauridsen et al. (2012) and Surlyk et al. (2013). The pterosaur bone fragments OESM 13096, 13323 and 13324, were found in the top of the Højerup Member of the Møns Klint Formation. C. Photograph of the locality, showing the sampling spot and its location relative to the K/Pg boundary layer, indicated by asterisk. Red dotted line indicates the placement of the K/Pg boundary layer where it is overgrown in the quarry. The two red poles in the middle are 1 meter high. Photograph: Sten Lennart Jakobsen.

Geological setting

The Maastrichtian chalk (Upper Cretaceous) in Denmark is prominently exposed in the coastal cliffs at Stevns and Møn and in inland quarries in northern Jylland (Fig. 1). At Stevns Klint, the K/Pg boundary succession is exposed at outcrops and quarries along the cliff side, and the uppermost Maastrichtian is represented by the Sigerslev and Højerup members of the Møns Klint Formation (Surlyk et al. 2013). The lowermost layers exposed at Stevns comprise the Sigerslev Member, which is prominently exposed along most of the cliff section. The top of the Sigerslev Member is characterised by a thick, nodular flint band and two incipient hardgrounds, which mark the transition to the bryozoan-rich, low-relief mounded chalk of the Højerup Member. These bryozoan mounds were part of the NW European epeiric “chalk sea”, and formed far from the nearest Fenno-Scandian landmass in relatively deep water below the photic zone and mostly below storm wave base (Surlyk 1997). The exact age of the Højerup Member is difficult to determine, as its basal level predates the terminal cooling event at ~200 kyr prior to the Cretaceous/Paleogene boundary. The incipient hardground at the base of the member, reflects a hiatus of unknown duration. Based on the calculated, average Late Maastrichtian sedimentation rate, the Højerup Member must represent a time span of about 50 000–60 000 years, within the last 200 000 years of the Cretaceous (Thibault et al. 2016; Thibault and Husson 2016). The stratigraphy of the K/Pg boundary layer is complex, resulting in the top of the Højerup Member being either an erosive surface and hardground, or it is overlain by the Fiskeler Member of the lower Danian Rødvig Formation (Surlyk et al. 2006). The Fiskeler Member is overlain by the Cerithium Limestone Member which is topped by an erosional hardground which is overlain by the lower Danian Stevns Klint Formation, with its prominent bryozoan mounds (Surlyk et al. 2006, 2013). The thickness of the Højerup Member varies along the cliff side, and at the Holtug quarry, the Højerup Member is approximately 1.5 metres thick (Surlyk et al. 2006).

Systematic palaeontology

Pterosauria Kaup, 1834

Pterosauria indet.

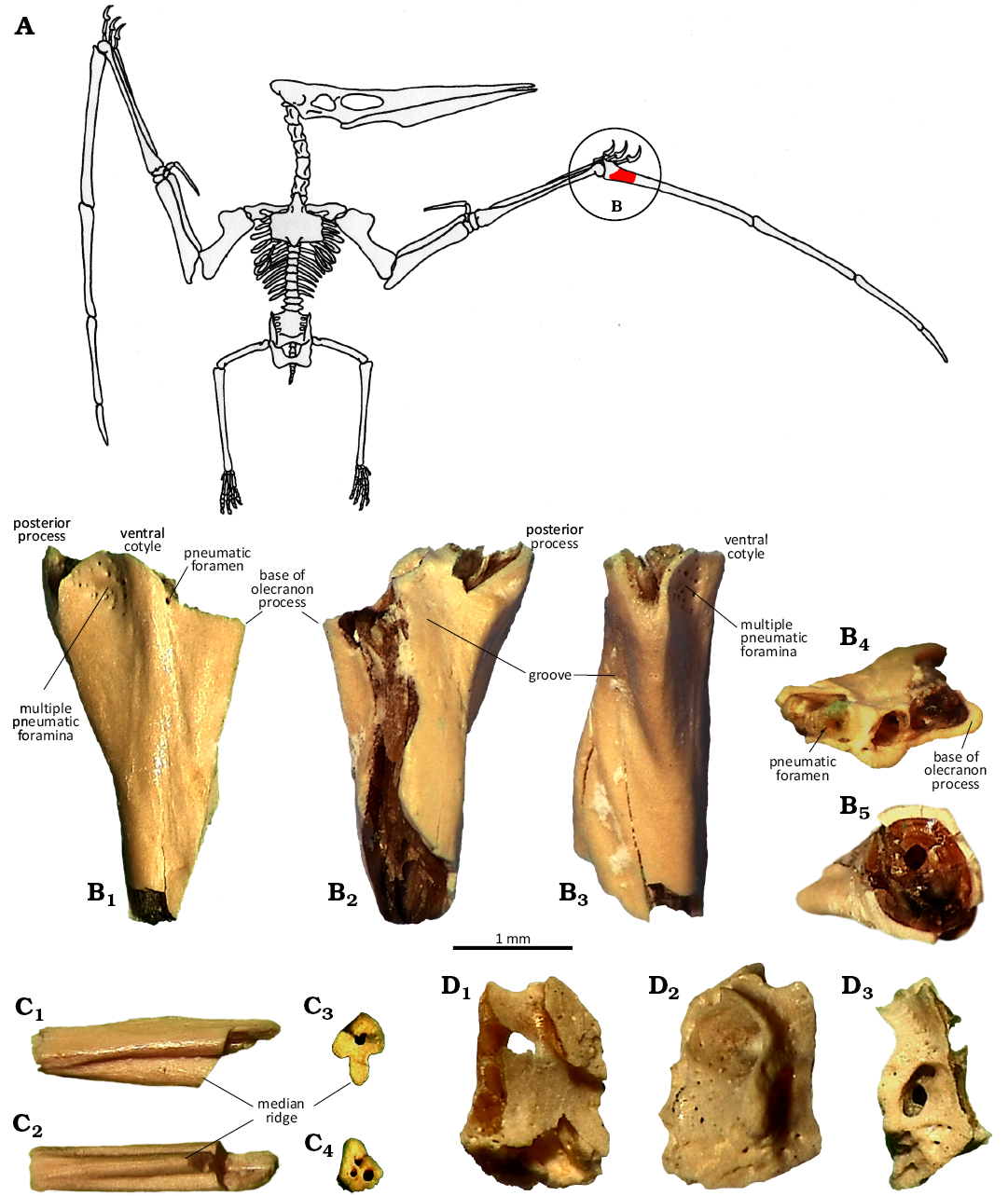

Fig. 2.

Material.—OESM 13096, 13323, and 13324, respectively a proximal fragment of a phalanx, a distal phalanx fragment and a unidentified pneumatized bone fragment from Holtug Quarry (55.341957N, 12.446692E), Stevns Klint, Denmark. Sampled level of chalk in the Højerup Member of the Møns Klint Formation immediately below the K/Pg boundary layer; uppermost Maastrichtian (Surlyk et al. 2006) six additional numbered specimens, OESM 13320–13322, 13325 –13327 remains unidentified.

Description.—OESM 13096 (Fig. 2B) is an incomplete proximal fragment of the left phalanx 1 of digit IV lacking the proximal articular surfaces and shaft. As preserved, the fragment measures 4.5 mm in length and 2.5 mm in max width. The interior cavities of the bone fragment are infilled with flint. OESM 13323 (Fig. 2C) is identified as a distal fragment of phalanx 2 or a proximal fragment of phalanx 3 of digit IV, which measures 2.5 mm in length as preserved. A total of 28 additional fossil bone fragments were subsequently recovered from the sample, after the initial discovery of OESM 13096. These display the same preservational appearances and characteristics as OESM 13096 (colour and flint-infilled cavities) and anatomical similarities such as numerous (pneumatic) foramina but are all smaller and as yet indeterminate (e.g., OESM 13324; Fig. 2D). While the fragments may represent multiple individuals or taxa, it is most likely they derive from a single individual specimen due to their common preservation and association within the same relatively small sample. In overall appearance, the proximal part of the phalanx 1 fragment is wide with a clear three-pronged expression and narrowing distally towards the ovoid cross-section of the shaft. More of the base of the posterior process has been preserved than the base of the olecranon process (Fig. 2B1, B2).

Fig. 2. Fragments of wing skeleton of Pterosauria indet. from the Maastrichtian–lower Danian, Højerup Member of the Møns Klint Formation, Holtug limestone quarry at Stevns Klint, Denmark. A. Drawing of idealized pterosaur skeleton showing location of fragment OESM 13096 in red (modified after Williston 1902). Not to scale. B. OESM 13096, left phalanx 1 of digit IV in ventral (B1), dorsal (B2), posterior (B3), proximal (B4), and distal (B5) views. C. OESM 13323, fragment of phalanx 2 or phalanx 3 of digit IV in lateral (C1) and ventral (C2) views, end cross-sections (C3, C4). D. OESM 13324, unidentifiable fragment displaying numerous (pneumatic) foramina, rotated around vertical axis in different views (D1, D2, D3).

The preserved part of the dorsal surface of phalanx 1 is dominated by a large fracture, but appears relatively flat with a shallow groove running posterodistally (Fig. 2B2). On the ventral surface, a cluster of 16 small pneumatic foramina, all piercing the bone wall, are situated on the lightly concave surface between the posterior process and the base of the ventral cotyle (Fig. 2B1). A singular, slightly larger pneumatic foramen is preserved on the opposite site of the ventral cotyle, immediately next to its base. In posterior aspect, a shallow groove is present. It is separated by two smaller interior ridges, which twist and extend slightly past the base of the posterior process (Fig. 2B3). In proximal aspect, the visible interior structure of the ventral cotyle and posterior process display small bone struts and thin interior trabeculae pierced by more pneumatic foramina (Fig. 2B4). The distal cross-section of the fragment is irregularly ovoid and displays thin (~0.15 mm) outer bone walls (Fig. 2B5). The phalanx 2 or 3 fragment is characterised by the presence of a broad, median ridge on the ventral surface (Fig. 2C1, C2). One outline of the cross-section of the medial end (Fig. 2C3) is shaped like an ace-of-spades, with an acute dorsal surface, rounded anterior and posterior edges, and a prominent ventrally oriented median ridge, as well as a single, medially situated opening. In contrast, the outline of the other end (Fig. 2C4) is irregularly triangular with blunt corners and three openings.

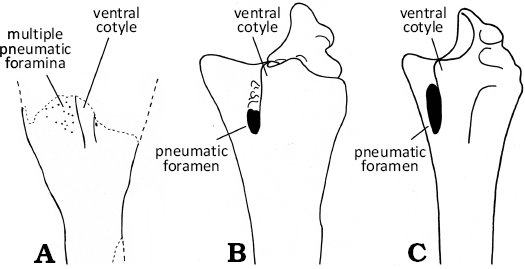

Remarks.—OESM 13096, 13323, 13324, and associated non-figured specimens OESM 13320–13322, 13325–13327 are referred to Pterosauria based on the extremely thin (~0.15 mm) outer bone walls (Fig. 2B5) and the presence of numerous pneumatic foramina piercing both the outer bone surface (Fig. 2B1) and the interior bone trabeculae (Fig. 2B4). Avian bones display similar anatomical features of pneumatic foramina and thin bone walls, but it was not possible to match the specific morphology of OESM 13096, 13323, and 13324 with the skeletons of any Cretaceous or Paleogene birds. Instead, as described below, their particular features can be identified in the digit IV wing finger skeleton of pterosaurs. In pterosaurs, the extremely hyperelongated digit IV supported the wing membrane and made up the leading edge of the outer wing. OESM 13096 is specifically identified as a fragment of a left proximal phalanx 1 of digit IV by comparison with similar elements showing the overall three-pronged expression of the posterior, ventral and olecranon processes (Fig. 3). As noted by Etienne et al. (2024), considerable morphological diversity exists in digit IVs phalanges among pterosaurs. The numerous smaller pneumatic foramina present on the ventral surface of the posterior process immediately next to the base of the ventral cotyle of OESM 13096 (Fig. 2B1) are considered homologous to singular pneumatic foramen present in the same location in several (Fig. 3), but not all pterosaurs; e.g., Santanadactylus pricei (Wellnhofer 1991: fig. 34); Anhanguera piscator (Kellner and Tomida 2000: fig. 43c, d); Alamodactylus byrdi (Andres and Myers 2013: fig. 4f); Caupedactylus ybaka (Kellner 2013: fig. 1). Where preserved in fossils of, or referred to, the Azdarchidae, a single pneumatic foramen is also present located in this position; cf. Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Frey and Martill 1996: figs. 5a–d, 6a); Azdarcho lancicollis (Averianov 2010: fig. 31d); Mistralazhdarcho maggii (Vullo et al. 2018: fig. 8a–d), distinguishing them from OESM 13096. OESM 13096 is similar in overall shape, yet distinguishable from the uncertain azhdarchid Navajodactylus boerie, which possess a single, small foramen situated on and next to the base of the ventral cotyle (Sullivan and Fowler 2011: figs. 3, 4). OESM 13323 (Fig. 2C1, C2) is interpreted as a distal shaft fragment of phalanx 2 or a proximal shaft fragment of phalanx 3, based on the broad, median ridge on the ventral surface, which is similar to and diagnostic of Azhdarchidae (Bennett 1994; Unwin and Lü 1997). Specifically, the shape and appearance of the ventral surface and area of origin of the median ridge of OESM 13323 (Fig. 2C1, C2) is similar to the distal shaft of phalanx 2 or proximal shaft of phalanx 3 of Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni (Andres and Langston 2021). However, unlike the T- or tau (τ)- shaped cross-section of azhdarchid wing phalanges 2 and 3 with flat (Bennett 1994; Unwin and Lü 1997; Andres and Langston 2021) or rounded dorsal surfaces (Azdarchidae indet. of Averianov 2007: pl. 8: 2), the cross-section in OESM 13323 is shaped like an ace-of-spades with an acute dorsal surface (Fig. 2C3). This also differs from the subtriangular or oval cross-section reported in the digit IV phalanges of Pteranodon (Bennett 2001).

Fig. 3. Comparative outlines of the proximal ends of phalanx 1 of digit IV redrawn to similar size from published figures as the left element in ventral aspect. A. Pterosauria indet. OESM 13096. B. Anhanguera piscator (Kellner & Tomida, 2000: fig. 43), NSM-PV 19892. C. Santanadactylus pricei (Wellnhofer, 1991: fig. 34), AMNH 22552. Not to scale.

Discussion

Due to the fragmentary nature of the specimens, it is not possible to make a more precise taxonomic referral of the specimen than Pterosauria, noting that there is also a large morphological diversity in the phalanges of digit IV (Etienne et al. 2024). The preserved fragments indicate the individual was perhaps 1/10 to 1/5 the size of the smallest of latest Maastrichtian pterosaurs from Morocco, Alcione elainus (visual comparison with FSAC-OB 4: referred right wing; Longrich et al. 2018: fig. 8) and loosely indicating that the animal had a wing span of perhaps just 20 to 50 cm in total. This is very significant, as it makes the new specimen the hitherto smallest known pterosaur from the Maastrichtian, indeed the Late Cretaceous.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine whether the new specimen is an adult or juvenile individual, as the specimen is broken below the epiphyseal area, where e.g. fusion with extensor tendon process could indicate ontogenetic age (Codorniú and Chiappe 2004). The very loose size estimate of a wingspan of 20 to 50 cm in total based on OESM 13096 corresponds both to the range recorded for hatchlings and young juveniles of taxa with adult wingspans of 1.9 m and above (Codorniú and Chiappe 2004; Unwin and Deeming 2019; Naish et al. 2021).

If the new pterosaur specimen derives from a near or fully grown adult individual, then it is evidence for the presence of at least one taxon of small-bodied pterosaurs persisting until the end of the Cretaceous. If it is instead a hatchling or juvenile of a large taxon, then another scenario presents itself. Hatchling pterosaurs were likely super-precocial and able to fly actively immediately after hatching, based on ossification patterns of flight apparatus in fossil embryos and modelling of flight capability and bone strength (Unwin and Deeming 2019; Naish et al. 2021; Smith et al. 2022). Modelling of flight capability also indicate that hatchling or juvenile pterosaurs were initially adapted to active sustained flight in restricted, vegetation-filled environments, growing into more efficient long-distance gliders necessarily utilizing more open environments, as their size increased. In turn, this supports niche partitioning in pterosaurs, where individuals at different ontogenetic stages occupied different ecological niches and environments (Naish et al. 2021; Smith et al. 2022). Niche partitioning has been advocated to explain the absence of fossils of hatchling or early juveniles of Pteranodon in the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway deposits of the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation, where the smallest known individual to date has an estimated wingspan of ~1.76 m (Bennett 2018). Against this stands the observation, that small-bodied juvenile pterosaurs appear to have been excluded from off-shore deposits (Smith et al. 2022), and the Højerup Member represents relatively deep water approximately 150 km off-shore (Surlyk 1997). Also, there is likely a general preservational bias against any remains of small pterosaurs during the Late Cretaceous, as even juvenile specimens of the recorded larger taxa are conspicuously absent (Martin-Silverstone et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2022). In this context, if the new specimen is a hatchling or juvenile, it does represent an anomaly, as it size-wise is much smaller than the smallest recorded Pteranodon, yet still deposited in relatively deep water far from the nearest landmass.

The specimen OESM 13096 is also well within the size range that of chronological and geographical contemporary latest Maastrichtian birds such as Asteriornis and Janavis from Belgium (Field et al. 2020, 2024; Benito et al. 2022), as well as the diverse avian assemblages of the roughly contemporaneous, but spatially more distant Hell Creek, Lance and Frenchman formations of North America (Longrich et al. 2011). Juveniles of large or giant pterosaur taxa took years to mature to full size (Bennett 2018). If they were also adapted to a niche of active sustained flight in restricted, vegetation-filled environments (Naish et al. 2021), they would have ecologically overlapped with contemporaneous birds. To our knowledge, this overlap has not been accounted for in hypotheses about competition with birds. In combination, this either calls for extreme caution about proposing, or invalidates hypotheses that latest Cretaceous pterosaurs and birds were involved in size-based niche partitioning to avoid ecological competition (Longrich et al. 2018, Yu et al. 2023).

Late Maastrichtian vertebrate fauna from Denmark.—The late Maastrichtian vertebrate fauna of the Danish chalk is diverse but very fragmentarily preserved. It comprises at least eight taxa of teleosteans, represented by skeletal remains and otoliths (Bonde et al. 2008; Bonde and Leal 2017; Schwarzhans and Milàn 2017). Chondrichthyans are represented by 31 species based on finds of isolated teeth (Adolfssen and Ward 2014) and coprolites (Milàn et al. 2015). Other vertebrates are present but are extremely rare. Four genera of mosasaurs are known, where Mosasaurus hoffmannii and Plioplatecarpus sp. are most abundant and known from both isolated teeth and extremely fragmentary skeletons (Lindgren and Jagt 2005). In addition to that, a single tooth from the durophagous mosasaur Carinodens minalmamar has been found (Milàn et al. 2018), and two teeth of Prognathodon (Giltaij et al. 2021), bringing the late Maastrichtian mosasaur diversity up to four genera. Crocodilians are represented by a few isolated tooth crowns from gavialoid crocodilians (Gravesen and Jakobsen 2012; Voiculescu-Holvad 2022), and turtles by a single carapace fragment of a chelonioid turtle (Karl and Lindow 2009).

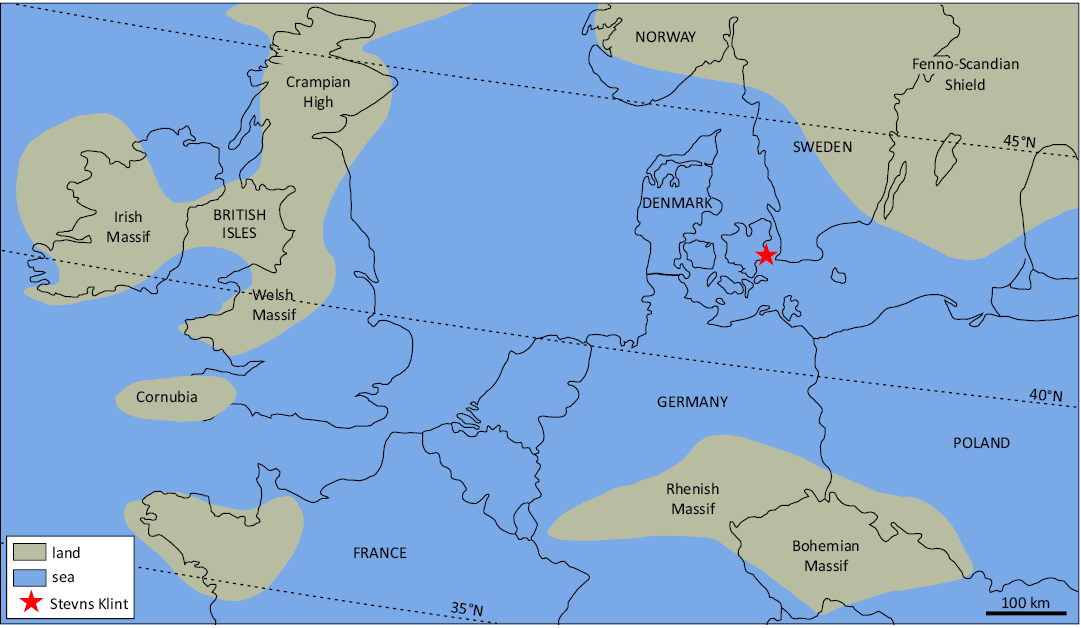

Up to now, no remains of bird or pterosaurs have been recorded. Small, so far undescribed presumed pterosaur bone fragments have been found in the upper Campanian and lower Maastrichtian deposits of southern Sweden (Einarsson 2018; Johan Lindgren, personal communication 2024), and birds are known from the Campanian deposits of Ivö Klack and Åsen, Southern Sweden (Sørensen et al. 2013), and the Maastrichtian type area in the Netherlands (Dyke et al. 2008). Furthermore, as the Højerup Member represents a relatively deep-water environment, far from the nearest landmass of Fenno-Scandia (Fig. 4), and below the photic zone and storm wave basis (Surlyk 1997), OESM 13096, 13323, and 13324 are also significant in documenting a rare small-bodied, flying vertebrate taxon preserved relatively far from the shoreline. This contrasts with the above-mentioned bird remains from the contemporaneous Maastricht Formation, which derive from a shallower, above storm-wave basis environment nearer to a terrestrial landmass (Kroth et al. 2024), that preserves absolutely more fragile vertebrate specimens.

The discovery of a pterosaur bone in the uppermost Maastrichtian chalk of Denmark, thus represents a new and important addition to the upper Maastrichtian vertebrate fauna of northern Europe. Specifically, the new specimen represents an important addition to the scarce record of end-Cretaceous diminutive pterosaurs as it is the geologically youngest and the first record from the Boreal Realm.

Fig. 4. Palaeogeographic map of northern Europe during the end Maastrichtian, showing the location of the present day Stevns Klint. The nearest coastline was at that time were located approximately 150 km northeast in the Fenno-Scandian landmass in what is today southern Sweden (modified from Ziegler 1990).

Conclusions

OESM 13096 and 13323 and associated remains OESM 13320–13322, 13324–13327 represent parts of phalanges 1 and 2 or 3 of digit IV of a pterosaur of possible Azhdarchid affinities. This is the first discovery of pterosaur material from the Maastrichtian chalk of Denmark. Stratigraphically, the pterosaur is among the youngest finds in the world, deriving from the last 50 000–60 000 years of the Cretaceous, and show that small-bodied pterosaurs with a wingspan below 50 cm persisted right up until the K/Pg boundary.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jingmai O’Connor (Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, USA) for valuable commentary on the taxonomic identification of the specimen. We are grateful to Mette Agersnap Grejsen Hofstedt (Hornslet, Denmark) for her diligent and thorough work in recovering additional bone fragments from the original sample, although they are as-yet anatomically indeterminate. We thank Roy Smith (University of Portsmouth, UK) and especially an anonymous reviewer as well as Acta Palaeontologica Polonica editor Daniel E. Barta (Oklahoma State University, Tahlequah, USA), for providing comments and suggestions, which substantially improved the manuscript.

Editor: Daniel E. Barta

References

Adolfssen, J.S. and Ward, D.J. 2014. Crossing the boundary: an elasmobranch fauna from Stevns Klint, Denmark. Palaeontology 57: 591–629. Crossref

Andres, B. and Langston Jr., W. 2021. Morphology and taxonomy of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41 (Supplement to 2): 46–202. Crossref

Andres, B. and Myers, T.S. 2013. Lone Star Pterosaurs. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 103: 383–398. Crossref

Averianov, A.O. 2007. New Records of Azhdarchids (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia. Paleontological Journal 41 (2): 189197 Crossref

Averianov, A.O. 2010. The osteology of Azhdarcho lancicollis Nessov, 1984 (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. Proceedings of the Zoological Institute Russian Academy of Sciences 314: 264–317. Crossref

Benito, J., Kuo, P.C., Widrig, K.E., Jagt, J.W.M., and Field, D.J. 2022. Cretaceous ornithurine supports a neognathous crown bird ancestor. Nature 612: 100–105. Crossref

Bennett, S.C. 1994. Taxonomy and systematics of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea). Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History University of Kansas 169: 1–70.

Bennett, S.C. 2001. The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon: Part I. General description of osteology. Palaeontographica A 260: 1–112. Crossref

Bennett, S.C. 2018. New smallest specimen of the pterosaur Pteranodon and ontogenetic niches in pterosaurs. Journal of Paleontology 92: 254–271. Crossref

Bonde, N. and Leal, M.E.C. 2017. Danian teleosteans of the North Atlantic region—compared with the Maastrichtian. Research & Knowledge 3: 50–54.

Bonde, N., Andersen, S., Hald, N., and Jakobsen, S.L. 2008. Danekræ – Danmarks bedste fossiler. 224 pp. Gyldendal, Copenhagen. Crossref

Codorniú, L. and Chiappe, L.M. 2004. Early juvenile pterosaurs (Pterodactyloidea: Pterodaustro guinazui) from the Lower Cretaceous of central Argentina. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 41: 9–18. Crossref

Dyke, G.J., McGowan, A.J., Nudds, R.L., and Smith, D. 2009. The shape of pterosaur evolution: evidence from the fossil record. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22: 890–898. Crossref

Dyke, G.J., Schulp, A.S., and Jagt, J.M.W. 2008. Bird remains from the Maastrichtian type area (Late Cretaceous). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 87: 353–358. Crossref

Einarsson, E. 2018. Palaeoenvironments, Palaeoecology and Palaeobiogeography of Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Faunas from the Kristianstad Basin, Southern Sweden, with Applications for Science Education. 171 pp. Doctoral Thesis, Lund University, Lund.

Etienne, J.L., Smith, R.E., Unwin, D.M., Smyth, R.S.H., and Martill, D.M. 2024. A ‘giant’ pterodactyloid pterosaur from the British Jurassic. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 135: 335–348. Crossref

Field, D.J., Benito, J., Chen, A., Jagt, J.W.M., and Ksepka, D.T. 2020. Late Cretaceous neornithine from Europe illuminates the origins of crown birds. Nature 579: 397–401. Crossref

Field, D.J., Benito, J., Werning, S., Chen, A., Kuo, P.-C., Crane, A., Widrig, K.E., Ksepka, D.T., and Jagt, J.W.M. 2024. Remarkable insights into modern bird origins from the Maastrichtian type area (north-east Belgium, south-east Netherlands). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 103: e15. Crossref

Frey, E. and Martill, D.M. 1996. A reappraisal of Arambourgiania (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea): One of the world’s largest flying animals. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen 199: 221–247. Crossref

Giltaij, T., Milàn, J., Jagt, J.W.M., and Schulp, A.S. 2021. Prognathodon (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Maastrichtian chalk of Denmark. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 69: 53–58. Crossref

Gravesen, P. and Jakobsen, S.L. 2012. Skrivekridtets fossiler. 153 pp. Gyldendal, Copenhagen.

Gravesen, P. and Jakobsen, S.L. 2013. Skrivekridtets fossiler. 168 pp. Gyldendal, Copenhagen.

Karl, H.-V. and Lindow, B.E.K. 2009. First evidence of a Late Cretaceous marine turtle (Testudines: Chelonioidea) from Denmark. Studia Geologica Salmanticensia 45: 175–180.

Kaup, J.J. 1834. Versuch einer Einteilung der Säugethiere in 6 Stämme und der Amphibien in 6 Ordnungen. Isis von Oken 3: 311–315.

Kellner, A.W.A. 2013. A new unusual tapejarid (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Early Cretaceous Romualdo Formation, Araripe Basin, Brazil. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 103: 409–421. Crossref

Kellner, A.W.A. and Tomida, Y. 2000. Description of a new species of Anhangueridae (Pterodactyloidea) with comments on the pterosaur fauna from the Santana Formation (Aptian–Albian), northeastern Brazil. National Science Museum Monographs 17: i–x + 1–135.

Kroth, M., Trabucho-Alexandre, J.P., Pimenta, M.P., Vis, G.-J., and De Boever, E. 2024. Facies characterisation and stratigraphy of the upper Maastrichtian to lower Danian Maastricht Formation, South Limburg, the Netherlands. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 103: e13. Crossref

Lauridsen, B.W., Bjerager, M., and Surlyk, F. 2012. The middle Danian Faxe Formation – new lithostratigraphic unit and a rare taphonomic window into the Danian of Denmark. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 60: 47–60. Crossref

Lindgren, J. and Jagt, J.W.M. 2005. Danish mosasaurs. In: A.S. Schulp and J.W.M. Jagt (eds.), Proceedings of the First Mosasaur Meeting. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences 84: 315–320. Crossref

Longrich, N.R., Martill, D.M., and Andres, B. 2018. Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. PLoS Biology 16 (3): e2001663. Crossref

Longrich, N.R., Tokaryk, T., and Field, D.J. 2011. Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108: 15253–15257. Crossref

Martill, D.M. and Smith, R.E. 2024. Cretaceous pterosaur history, diversity and extinction. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 544: 501–524. Crossref

Martin-Silverstone, E., Witton, M.P., Arbour, V.M., and Currie, P.J. 2016. A small azhdarchoid pterosaur from the latest Cretaceous, the age of flying giants. Royal Society open science 3: 160333. Crossref

McGowan, A.J. and Dyke, G.J. 2007. A morphospace-based test for competitive exclusion among flying vertebrates: did birds, bats and pterosaurs get in each other’s space? Journal of Evolutionary Biology 20: 1230–1236. Crossref

Milàn, J., Hunt, A.P., Adolfssen, J.S., Rasmussen, B.W., and Bjerager, M. 2015. First record of a vertebrate coprolite from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) chalk of Stevns Klint, Denmark. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 67: 227–229.

Milàn, J., Jagt, J.W.M., Lindgren, J., and Schulp, A.S. 2018. First record of Carinodens (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the uppermost Maastrichtian of Stevns Klint, Denmark. Alcheringa 42: 597–602. Crossref

Naish, D., Witton, M.P., and Martin-Silverstone, E. 2021. Powered flight in hatchling pterosaurs: evidence from wing form and bone strength. Scientific Reports 11: 13130. Crossref

Schwarzhans, W. and Milàn, J. 2017. After the disaster: bony fish remains (mostly otoliths) from the K/Pg boundary section at Stevns Klint, Denmark, reveal consistency with teleost faunas from later Danian and Selandian strata. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 65: 59–74. Crossref

Smith, R.E., Chinsamy, A., Unwin, D.M., Ibrahim, N., Zouhri, S., and Martill, D.M. 2022. Small, immature pterosaurs from the Cretaceous of Africa: implications for taphonomic bias and palaeocommunity structure in flying reptiles. Cretaceous Research 130: 105061. Crossref

Sørensen, A.M, Surlyk, F., and Lindgren, J. 2013. Food resources and habitat selection of a diverse vertebrate fauna from the upper lower Campanian of the Kristianstad Basin, southern Sweden. Cretaceous Research 42: 85–92. Crossref

Sullivan, R.M. and Fowler, D.W. 2011. Navajodactylus boerei, n. gen., n. sp., (Pterosauria, ?Azhdarchidae) from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation (upper Campanian) of New Mexico. Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 53: 393–404.

Surlyk, F. 1972. Morphological adaptations and population structures of the Danish chalk brachiopods (Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous). Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Biologiske Skrifter 19 (2): 1–57.

Surlyk, F. 1997. A cool-water carbonate ramp with bryozoan mounds: Late Cretaceous–Danian of the Danish basin. SEPM Special Publication 56: 293–307. Crossref

Surlyk, F., Damholt, T., and Bjerager, M. 2006. Stevns Klint, Denmark: uppermost Maastrichtian chalk, Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary, and lower Danian bryozoan mound complex. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 54: 1–48. Crossref

Surlyk, F., Rasmussen, S.L., Boussaha, M., Schiøler, P., Skovsbo, N.H., Sheldon, E., Stemmerik, L., and Thibault, N. 2013. Upper Campanian–Maastrichtian holostratigraphy of the eastern Danish Basin. Cretaceous Research 46: 232–256. Crossref

Thibault, N. and Husson, D. 2016. Climatic fluctuations and sea-surface water circulation patterns at the end of the Cretaceous era: calcareous nannofossil evidence. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 441: 152–164. Crossref

Thibault, N., Harlou, R., Schovsbo, N.H., Stemmerik, L., and Surlyk, F. 2016. Late Cretaceous (late Campanian–Maastrichtian) sea-surface temperature record of the Boreal Chalk Sea. Climate of the Past 12: 429–438. Crossref

Thomsen, E. 1995. Kalk og kridt i den danske undergrund. In: O.B. Nielsen (ed.), Danmarks geologi fra Kridt til i dag. Århus Geokompendier 1: 31–68.

Unwin, D.M. and Deeming, D.C. 2019. Prenatal development in pterosaurs and its implications for their postnatal locomotory ability. Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B 286: 20190409. Crossref

Unwin, D.M. and Lü, J. 1997. On Zhejiangopterus and the relationship of pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Historical Biology 12: 199–210. Crossref

Voiculescu-Holvad, C. 2022. Historical material of cf. Thoracosaurus from the Maastrichtian of Denmark provides new insight into the K/Pg distribution of Crocodylia. Cretaceous Research 139: 105309. Crossref

Vullo, R., Garcia, G., Godefroit, P., Cincotta, A., and Valentin, X. 2018. Mistralazhdarcho maggii, gen. et sp. nov., a new azhdarchid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of southeastern France. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 38 (4): 1–16. Crossref

Wellnhofer, P. 1991. Weitere Pterosaurierfunde aus der Santana-Formation (Apt) der Chapada do Araripe, Brasilien. Palaeontographica A 215: 43–101.

Williston, S.W. 1902. On the skeleton of Nyctodactylus, with restoration. American Journal of Anatomy 1: 297–305. Crossref

Yu, Y., Zhang, C., and Xing, X. 2023. Complex macroevolution of pterosaurs. Current Biology 33: 770–779. Crossref

Ziegler, P.A. 1990. Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe. 2nd Edition. 239 pp. Geological Society Publishing House, Bath.

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 723–730, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01252.2025