Rare, but not unique: a new specimen of the enigmatic gecko Rhodanogekko vireti from the lower Oligocene of southern Germany

ANDREA VILLA and MICHAEL RUMMEL

Rhodanogekko vireti is one of the least known extinct geckos. It was described based on an isolated frontal from the middle Eocene of France, which until now includes the only material assigned to this species. In this contribution, we report an additional isolated frontal, coming from the lower Oligocene of southern Germany, which can be attributed to R. vireti based on a strong middle constriction and a dorsal rugose sculpturing. The new fossil extends the stratigraphic record of the species by about 10 Myr, and it is the first evidence for its presence outside France. The phylogenetic position of Rhodanogekko is still uncertain, but affinities with Sphaerodactylidae were suggested previously. If this is correct, the new frontal from Germany would fit into a stratigraphic gap without recorded confident sphaerodactylids in Europe, spanning the entire Oligocene. However, Rhodanogekko lacks the posterodorsal depressions or grooves apomorphic for frontals of Euleptinae, the subfamily including all European sphaerodactylids, extant and extinct. Additional fossils are needed to understand the relationships between Rhodanogekko and other gekkotans, and we here highlight the potential borne by the late Paleogene fossil record from southern Germany for new discoveries of these reptiles.

Introduction

Geckos are rare findings in the fossil record (Estes 1983; Daza et al. 2014; Villa and Delfino 2019; Villa et al. 2022). Despite this, several extinct species are known, mostly from Europe and in most cases represented only by isolated and fragmentary bones (Hoffstetter 1946; Schleich 1987; Müller 2001; Augé 2003, 2005; Bolet et al. 2015; Čerňanský et al. 2018, 2022, 2023; Georgalis et al. 2021; Villa 2023; but see Bauer et al. 2005, and Villa et al. 2022, for two notable exceptions). Well preserved specimens are also available as inclusions in amber (Böhme 1984; Bauer et al. 2005; Arnold and Poinar 2008; Daza and Bauer 2012; Daza et al. 2014, 2016). Among the least known extinct geckos is Rhodanogekko vireti Hoffstetter, 1946, whose holotype and only known specimen is an isolated frontal from the middle Eocene of Lissieu, in France. We here report an additional frontal (NMA 2025-2/2197), which can be assigned to R. vireti due to morphological congruence with the holotype. The specimen comes from the locality Weißenburg 23 (Fig. 1B), which was located in the quarry of the company “Schotter-und Steinwerk Weißenburg” (Bavaria, district of Mittelfranken), and more precisely in the north-eastern former extraction area of the quarry. The locality was a karst fissure filling in the Jurassic limestone (Malm Delta), exposed in the years 2009 and 2010 over several meters directly below the ground surface to a depth of 3 m. The matrix of different coloured clays contained components such as iron ores, boulders from the White Jurassic limestones, and Cretaceous relics. The finds of isolated fossils yielded a small Oligocene (Rupelian, MP 21/22) fauna with Palaeotherium medium Cuvier, 1804, Diplobune bavarica Fraas, 1870, Pseudosciurus suevicus Hensel, 1856, and Suevosciurus ehingensis Dehm, 1937.

Institutional abbreviations.—NMA, Naturmuseum der Stadt Augsburg, Germany.

Material and methods

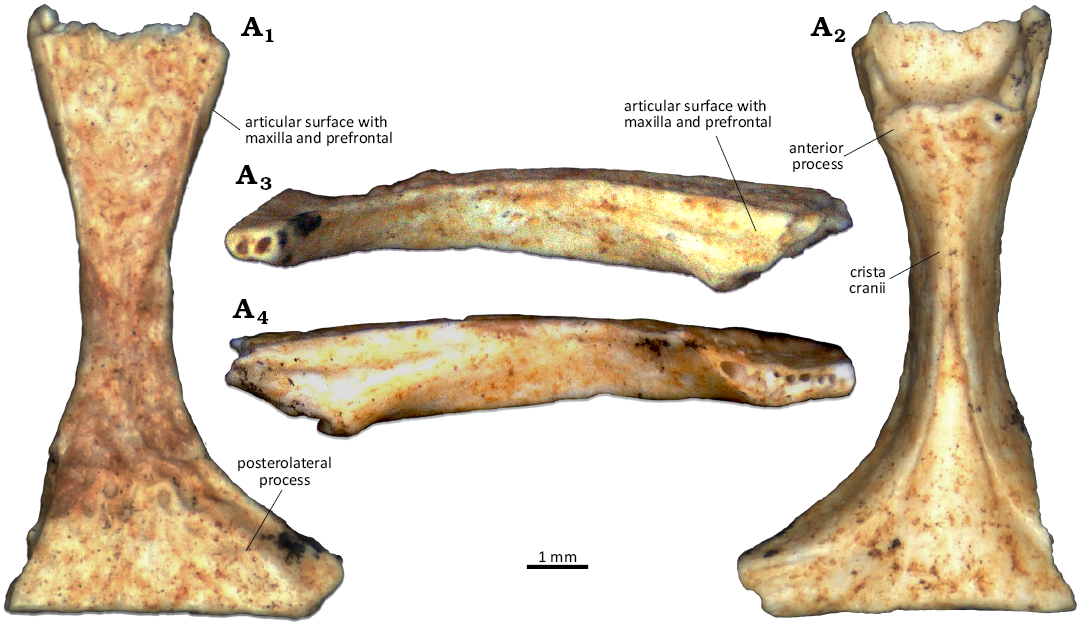

NMA 2025-2/2197 (Fig. 2) is housed in the Naturmuseum der Stadt Augsburg (NMA). Terminology used in the descriptions follows Villa et al. (2018). Measurements were taken with ImageJ v. 1.54 (Rasband 1997–2018).

Systematic palaeontology

Order Squamata Oppel, 1811

Infraorder Gekkota Camp, 1923

Genus Rhodanogekko Hoffstetter, 1946

Type species: Rhodanogekko vireti Hoffstetter, 1946 (Lissieu, France; middle Eocene).

Rhodanogekko vireti Hoffstetter, 1946

Fig. 2.

Material.—NMA 2025-2/2197, an isolated frontal; Weißenburg 23, Bavaria, Germany, early Oligocene.

Description.—NMA 2025-2/2197 is a fairly complete unpaired frontal, missing the entire left posterolateral process, as well as the tip of the right posterolateral process, and with a damaged anterior end. The preserved length (i.e., measured as the longitudinal line from the most anterior preserved portion, located at the left anterolateral corner, to the frontoparietal suture) of the frontal is 9.8 mm, but the broken anterior end could have made up for 0.5 or 1 mm more. The frontal is narrow, with a strongly constricted middle portion that expands slightly at the anterior end and to a higher extent at the posterior end. The width at the narrowest point, at about midlength, is about 1.5 mm. The dorsal surface is almost completely covered by a low dermal sculpturing made up of closely packed rugosities (more scattered in the posterior portion). The size of the rugosities varies, but they are moderately large when considered in proportion with the bone. Only the posterolateral processes are smooth. Posterior to the middle constriction, the dorsal surface is slightly concave, while it is flat in the rest of the bone. There are no depressions or grooves along the lateral margins of the frontal, which are slightly raised instead. Due to the breakage, the morphology of the anterior end of the frontal (i.e. mainly the area articulating with the nasals, which is completely missing) cannot be evaluated. The posterior end displays a straight posterior margin and well-developed and wide posterolateral processes. The preserved part of frontoparietal suture is 5.1 mm wide, but this is only a part of the original width due to the missing portion of the posterolateral processes. Ventrally, the cristae cranii are well developed and partially fuse at midline. This fusion is complete only in the anterior portion of the frontal, and the cristae clearly separate at midlength, leaving posteriorly a wide opening in ventral view. A closed suture line is also visible in the posterior half of the fused portion of the cristae, a potential evidence of immaturity. Anteriorly, the anterior processes of the cristae cranii are very short. The exposed ventral surface of the frontal is flat both anteriorly and posteriorly, with no ridge at midline. By the distal end of the preserved posterolateral process, a low ridge on the lateral margins marks a slender and triangular articulation surface developed along the margin on the ventral surface. On each lateral surface of the frontal, there is a very long and slender articulation surface for the maxilla and prefrontal, reaching about midlength of the bone. A clear articulation surface with the postorbitofrontal, on the other hand, is not visible.

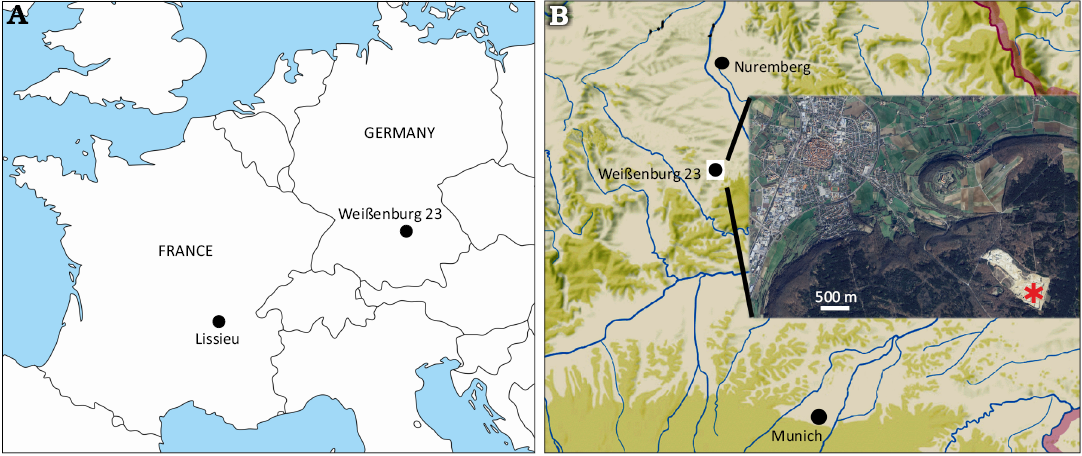

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Rhodanogekko vireti is only known from its type locality (Lissieu, middle Eocene of France) and the new occurrence reported herein from the lower Oligocene of Germany (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Locations of the two known occurrences of Rhodanogekko vireti Hoffstetter, 1946. A. Map of France and Germany with the localities of Lissieu (type locality of the species) and Weißenburg 23. B. Map with the location of the village of Weißenburg in Bavaria, Germany, and the location of Weißenburg 23 (asterisk) in the “Schotter-und-Steinwerk Weißenburg” quarry. Map in A based on an original from d-maps (https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=2232&lang=en).

Discussion

Among gekkotans, the combination of a strong frontal constriction and dorsal rugose sculpturing is unique to R. vireti, which was most likely a large gecko with large eyes (Daza et al. 2014). The constricted frontal, together with the fused cristae cranii, further implies a narrowed olfactory tract for this extinct gecko. The new fossil from Weißenburg 23 shares the above-mentioned frontal features with the holotype of the species, but it is much smaller (the holotype is more than 13 mm in anteroposterior length, based on the photos provided by Daza et al. 2014: fig. 4). This size difference might be accounted for by a potential younger ontogenetic stage of NMA 2025-2/2197, which can be inferred from the incomplete obliteration of the midline suture between the cristae cranii. Attribution of NMA 2025-2/2197 to R. vireti widely extends the stratigraphic record of this species, for about 10 Myr from the middle Eocene well into the Oligocene. It further highlights its presence in southern Germany, at least for its youngest occurrence. The precise phylogenetic relationships of Rhodanogekko are currently unknown: recent phylogenetic analyses including fossil gekkotans from Europe (Villa et al. 2022; Villa 2023) consistently recovered it nested within the Australian endemic Carphodactylidae Kluge, 1967, but this is likely due to convergence in frontal morphology and poor knowledge of Rhodanogekko. Rugose sculpturing in geckos evolved several times in pygopodoids, but at least once also in gekkonoids (Glynne et al. 2020: fig. 5). Daza et al. (2014) reported similarities between the frontals of Rhodanogekko and the sphaerodactylid Pristurus Rüppell, 1835, mainly based on the constriction. However, Rhodanogekko clearly differs from Pristurus, because in the latter the frontal is unsculpted (Daza et al. 2014: fig. 4C) and the cristae cranii are not fused ventrally (thus, lacking the tubular frontal of other gekkotans; Daza et al. 2014: fig. 4D). Affinity of Rhodanogekko with Sphaerodactylidae Underwood, 1954, would be much less problematic from a biogeographical point of view: as a matter of fact, sphaerodactylids are the dominant gekkotan family in Europe in the Paleogene and Neogene, based on our current knowledge of the fossil records of these squamates (Villa et al. 2022), and their remains were found both in Western and Central Europe. New fossils with Rhodanogekko-like frontals and additional bones associated are needed to solve this phylogenetic conundrum. Nevertheless, if Rhodanogekko is indeed a sphaerodactylid, the frontal from Weißenburg 23 would fit into the Oligocene gap spanning from the youngest Eocene species to the oldest Miocene ones, providing much needed information on the evolutionary history of this family just prior to the appearance in the Early Miocene of the first representatives of its only extant survivor in Europe (Euleptes Fitzinger, 1843, only living in western Mediterranean countries nowadays; Delaugerre et al. 2011). Additional occurrences of indeterminate gekkotan fossils with potential sphaerodactylid affinities reported by Čerňanský et al. (2016) from the upper Oligocene of Herrlingen 9 and 11, also in southern Germany, are further significant in this respect. On the other hand, Rhodanogekko clearly lacks dorsal depressions or grooves along the lateral margins in the posterior half of the frontal, the presence of which is the apomorphy of the subfamily encompassing all unambiguous sphaerodactylid genera from Europe, i.e., Euleptinae Villa et al., 2022. If part of the same family, Rhodanogekko might represent either a totally unrelated, non-euleptine taxon coexisting in Europe with the oldest known euleptines, a close relative who did not developed the apomorphic frontal feature yet, or even an euleptine who reversed to an undepressed/ungrooved frontal morphology.

Fig. 2. Frontal (NMA 2025-2/2197) of the gekkotan squamate Rhodanogekko vireti Hoffstetter, 1946 from the lower Oligocene of Weißenburg 23, Bavaria, Germany, in dorsal (A1), ventral (A2), right (A3), and left (A4) lateral views.

Conclusions

Based on the new isolated frontal, we were able to identify the second fossil known of one of the most enigmatic extinct gekkotan species, R. vireti. The strongly constricted frontal morphology and the dermal sculpturing on the dorsal surface of the bone confidently allows an attribution to this species. This new occurrence stands out as evidence that Rhodanogekko survived in Europe for a long time (at least from the middle Eocene to the early Oligocene) and that its past distribution was more widespread and not limited to France, where the type locality is situated. Despite its unique morphology, Rhodanogekko is a significant taxon to understand the evolution of the European gekkotans, given that it could be related to sphaerodactylids but clearly not part of Euleptinae, the subfamily to which most of the extinct geckos from Europe belong. Its morphological affinities with Pristurus could suggest the presence in the Paleogene of Europe of similar geckos, with large eyes, narrow frontals, and perhaps short snouts. Given that we only know Rhodanogekko based on two isolated frontals, new fossils are needed, including additional skeletal elements which could be associated with Rhodanogekko-like frontals. Southern Germany proves promising for new discoveries on these reptiles, and further explorations of the late Paleogene fossil record from the area, looking for remains of geckos, are highly anticipated.

Acknowledgments.—We are very grateful to the company Schotter- und Steinwerk Weißenburg GmbH for their permission to recover the material and their interest in the scientific work and documentation of the fossil finds. The editor, Daniel E. Barta (Oklahoma State University, Tahlequah, USA), and the two reviewers, Andrej Čerňanský (Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia and University of Warsaw, Poland) and Juan D. Daza (Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, USA), are kindly thanked; their comments and suggestions improved a previous version of this contribution. We also thank David P. Groenewald (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, Sabadell, Spain) for discussing with us some grammar doubts on the title. Project supported by: R+D+I project PID2020-117289GB-I00 (AEI/10.13039/501100011033), funded by the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación; Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca, Departament de Recerca i Universitats, Generalitat de Catalunya (Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral grant 2021 BP 00038); Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, Generalitat de Catalunya (2021 SGR 00620); and CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

Editor: Daniel E. Barta

References

Arnold, E.N. and Poinar, G. 2008. A 100 million year old gecko with sophisticated adhesive toe pads, preserved in amber from Myanmar. Zootaxa 1847: 62–68. Crossref

Augé, M. 2003. La faune de Lacertilia (Reptilia, Squamata) de l’Éocène inférieur de Prémontré (Bassin de Paris, France). Geodiversitas 25: 539–574.

Augé, M.L. 2005. Évolution des lézards du Paléogène en Europe. Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle 192: 1–369.

Bauer, A.M., Böhme, W., and Weitschat, W. 2005. An early Eocene gecko from Baltic amber and its implications for the evolution of gecko adhesion. Journal of Zoology 265: 327–332. Crossref

Böhme, W. 1984. Erstfund eines fossilien Kugelfingergeckos (Sauria: Gekkonidae: Sphaerodactylinae) aus Dominikanischem Bernstein (Oligozän von Hispaniola, Antillen). Salamandra 20: 212–220.

Bolet, A., Daza, J.D., Augé, M., and Bauer, A.M. 2015. New genus and species names for the Eocene lizard Cadurcogekko rugosus Augé, 2005. Zootaxa 3985: 265–274. Crossref

Camp, C.L. 1923. Classification of the lizards. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 48: 289–481.

Čerňanský, A., Daza, J.D., and Bauer, A.M. 2018. Geckos from the middle Miocene of Devínska Nová Ves (Slovakia): new material and a review of the previous record. Swiss Journal of Geosciences 111: 183–190. Crossref

Čerňanský, A., Daza, J.D., Smith, R., Bauer, A.M., Smith, T., and Folie, A. 2022. A new gecko from the earliest Eocene of Dormaal, Belgium: a thermophilic element of the ‘greenhouse world’. Royal Society Open Science 9: 220429. Crossref

Čerňanský, A., Daza, J.D., Tabuce, R., Saxton, E., and Vidalenc, D. 2023. An early Eocene pan-gekkotan from France could represent an extra squamate group that survived the K/Pg extinction. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 68: 695–708. Crossref

Čerňanský, A., Klembara, J., and Müller, J. 2016. The new rare record of the late Oligocene lizards and amphisbaenians from Germany and its impact on our knowledge of the European terminal Palaeogene. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 96: 559–587. Crossref

Cuvier, G. 1804. Sur les espèces d’animaux dont proviennent les os fossiles répandus dans la pierre à plâtre des environs de Paris. Annales du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris 3: 275–303.

Daza, J.D. and Bauer, A.M. 2012. A new amber-embedded sphaerodactyl gecko from Hispaniola, with comments on the morphological synapomorphies of the Sphaerodactylidae. Breviora 529: 1–28. Crossref

Daza, J.D., Bauer, A.M., and Snively, E.D. 2014. On the fossil record of the Gekkota. The Anatomical Record 97: 433–462. Crossref

Daza, J.D., Stanley, E.L., Wagner, P., Bauer, A.M., and Grimaldi, D.A. 2016. Mid-Cretaceous amber fossils illuminate the past diversity of tropical lizards. Science Advances 2: e1501080. Crossref

Dehm, R. 1937. Über die alttertiäre Nager Familie Pseudosciuridae und ihr Entwicklung. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, BeilBand B 77: 268–290.

Delaugerre, M., Ouni, R., and Nouira, S. 2011. Is the European Leaf-toed gecko Euleptes europaea also an African? Its occurrence on the Western Mediterranean landbrige islets and its extinction rate. Herpetology Notes 4: 127–137.

Estes, R. 1983. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie 10A. Sauria terrestria, Amphisbaenia. 249 pp. Friedrich Pfeil, Munich.

Fitzinger, L. 1843. Systema reptilium (Amblyglossae). 106 pp. Braumüller et Seidel, Vienna.

Fraas, O.F. 1870. Diplobune bavaricum. Palaeontographica 17: 177–184.

Georgalis, G.L., Čerňanský, A., and Klembara, J. 2021. Osteological atlas of new lizards from the Phosphorites du Quercy (France), based on historical, forgotten, fossil material. Geodiversitas 43: 219–293. Crossref

Glynne, E., Daza, J.D., and Bauer, A.M. 2020. Surface sculpturing in the skull of gecko lizards (Squamata: Gekkota). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 131: 801–813. Crossref

Hensel, R. 1856. Beiträge zur Kenntniss fossiler Säugethiere. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft 8: 660–704.

Hoffstetter, R. 1946. Sur les Gekkonidae fossiles. Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle 18 (2): 195–203.

Kluge, A.G. 1967. Systematics, phylogeny, and zoogeography of the lizard genus Diplodactylus Gray (Gekkonidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 15: 1007–1108. Crossref

Müller, J. 2001. A new fossil species of Euleptes from the early Miocene of Montaigu, France (Reptilia, Gekkonidae). Amphibia-Reptilia 22: 341–348. Crossref

Oppel, M. 1811. Die Ordnungen, Familien und Gattungen der Reptilien, als Prodrom einer Naturgeschichte derselben. 86 pp. Joseph Lindauer, Munich. Crossref

Rasband, W.S. 1997–2018. ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, https://imagej.net/ij/.

Rüppell, E. 1835. Neue Wirbelthiere zu der Fauna von Abyssinien gehörig, entdeckt und beschrieben. Amphibien. 18 pp. S. Schmerber, Frankfurt a. M. Crossref

Schleich, H.H. 1987. Neue reptilienfunde aus dem Tertiär Deutschlands. 7. Erstnachweis von Geckos aus dem Mittelmiozän Süddeutschlands: Palaeogekko risgoviensis nov. gen., nov. spec. (Reptilia, Sauria, Gekkonidae). Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Palaeontologie und Historische Geologie 27: 67–93.

Underwood, G. 1954. On the classification and evolution of geckos. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 124: 469–492. Crossref

Villa, A. 2023. A redescription of Palaeogekko risgoviensis (Squamata, Gekkota) from the Middle Miocene of Germany, with new data on its morphology. PeerJ 11: e14717. Crossref

Villa, A. and Delfino, M. 2019. Fossil lizards and worm lizards (Reptilia, Squamata) from the Neogene and Quaternary of Europe: an overview. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology 138: 177–211. Crossref

Villa, A., Daza, J.D., Bauer, A.M., and Delfino, M. 2018. Comparative cranial osteology of European gekkotans (Reptilia, Squamata). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 184: 857–895. Crossref

Villa, A., Wings, O., and Rabi, M. 2022. A new gecko (Squamata, Gekkota) from the Eocene of Geiseltal (Germany) implies long-term persistence of European Sphaerodactylidae. Papers in Palaeontology 8 (3): e1434. Crossref

Andrea Villa [andrea.villa@icp.cat; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6544-5201 ], Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP-CERCA), Edifici ICTA-ICP, c/ Columnes s/n, Campus de la UAB, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain.

Michael Rummel [michael.rummel@augsburg.de; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8761-166X ], Naturmuseum der Stadt Augsburg, Ludwigstraße 14, 86152, Augsburg, Germany.

Received 9 April 2025, accepted 4 August 2025, published online 1 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 A. Villa and M. Rummel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 699–703, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01257.2025