Review of the dental pattern in the squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans, and a description of two new Jurassic shark genera

ARNAUD BEGAT, EDUARDO VILLALOBOS-SEGURA, PATRICK L. JAMBURA, MANUEL A. STAGGL, STEFANIE KLUG, and JÜRGEN KRIWET

Begat, A., Villalobos-Segura, E., Jambura, P.L., Staggl, M.A., Klug, S., and Kriwet. J. 2025. Review of the dental pattern in the squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans, and a description of two new Jurassic shark genera. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 70 (4): 731–748.

The extinct elasmobranch Protospinax is an intriguing shark known mostly from isolated teeth and rare complete skeletons. Most previous studies focused on differences in isolated teeth for taxonomic assignments, with little to no considerations of dental variations. In this study we provide a detailed morphological evaluation of the dentition of the squalomorph shark, Protospinax based on three skeletal remains of Protospinax annectans from the famous Upper Jurassic lithographic limestone of the Solnhofen area (Bavaria, Germany) with partially preserved dentitions and isolated teeth from the Kimmeridgian of Mahlstetten (Baden-Württemberg, Germany). The aim of this study is to clarify ambiguities in dental morphologies and to establish heterodonty patterns, allowing to taxonomically reassess species previously assigned to Protospinax. Accordingly, we consider Protospinax annectans (Callovian–Aptian?), Protospinax carvalhoi (Bathonian), Protospinax lochensteinensis (Oxfordian), and Protospinax planus (Kimmeridgian) as valid species. The species of Protospinax bilobatus is considered a junior synonym of Protospinax magnus. Furthermore, our results show that the dental morphologies of P. magnus and Protospinax? muftius are very different from those of other Protospinax species and rather resemble those of orectolobiforms. Consequently, we introduce two new orectolobiform genera, Jurascyllium gen. nov. and Archaeoscyllium gen. nov., to accommodate these species. The review of the species confirms a stratigraphic range of Protospinax extending from the Toarcian (Lower Jurassic) to the Valanginian (Lower Cretaceous).

Key words: Elasmobranchii, Protospinaciformes, Orectolobiformes, Mesozoic.

Arnaud Begat [arnaud.begat@univie.ac.at; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0017-8346 ], Manuel A. Staggl [manuel.andreas.staggl@univie.ac.at; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3068-3098 ], and Jürgen Kriwet [juergen.kriwet@univie.ac.at; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6439-8455 ], University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Josef-Holaubek-Platz 2, 1090 Vienna, Austria; University of Vienna, Vienna Doctoral School of Ecology and Evolution (VDSEE), Djerassiplatz 1, 1030 Vienna, Austria.

Eduardo Villalobos-Segura [eduardo.villalobos.segura@univie.ac.at; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5475-6143 ] and Patrick L. Jambura [patrick.jambura@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4765-5042], University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Josef-Holaubek-Platz 2, 1090 Vienna , Austria.

Stefanie Klug [stefanie.klug@gauss.uni-goettingen.de; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9437-7236 ], Georg-August University School of Science (GAUSS), Georg-August Universität Göttingen, 37077 Göttingen, Germany.

Received 24 April 2025, accepted 11 September 2025, published online 10 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 A. Begat et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Protospinax Woodward, 1918, is an intriguing extinct elasmobranch taxon, characterised by a dorsoventrally flattened body and crushing dentition (Woodward 1918; Maisey 1976; Thies and Leidner 2011), indicative of a benthic lifestyle. Its known fossil record ranges from the Lower Jurassic to the Lower Cretaceous, with remains found in Europe and Russia (Woodward 1918; Delsate and Lepage 1990; Kriwet 2003; Delsate and Felten 2015; Guinot et al. 2014; Jambura et al. 2023). Currently, the genus comprises seven species: Protospinax bilobatus Underwood & Ward, 2004b (Bathonian), Protospinax carvalhoi Underwood & Ward, 2004b (Bathonian), Protospinax magnus Underwood & Ward, 2004b (Bathonian), Protospinax? muftius Thies, 1982 (Callovian), Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (Callovian–Tithonian), Protospinax lochensteinensis Thies, 1982 (Oxfordian), and Protospinax planus Underwood, 2002 (Kimmeridgian).

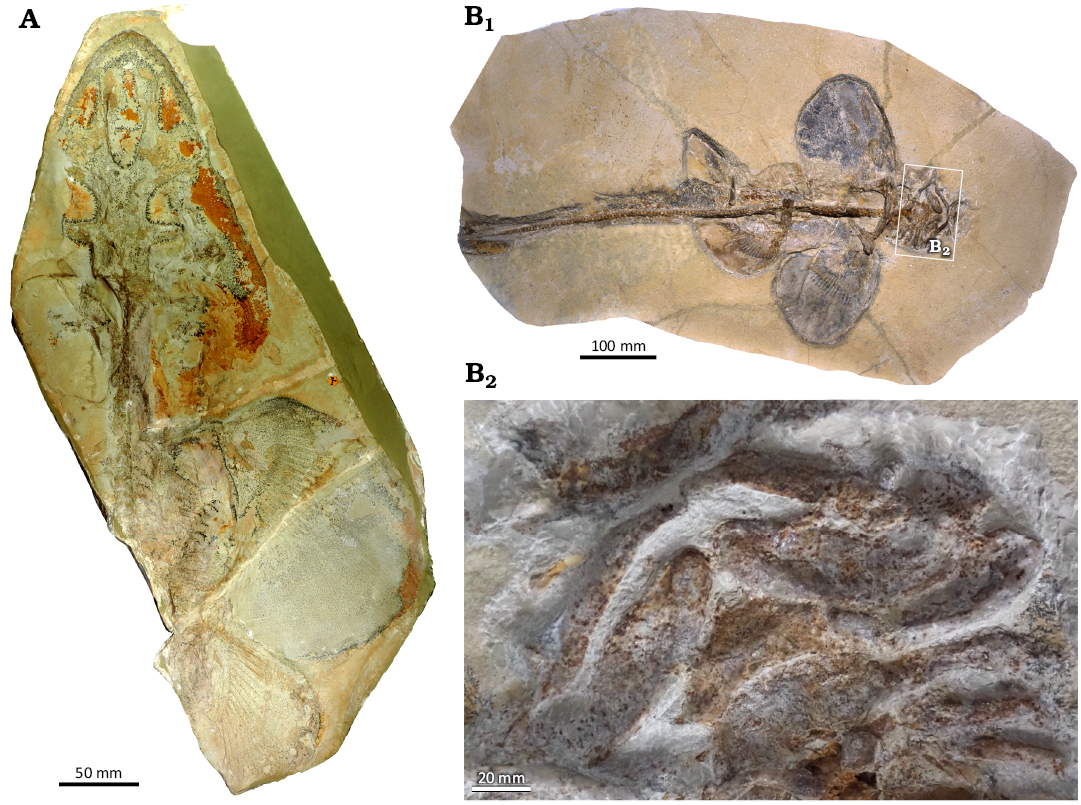

The systematic position of Protospinax has a long and confusing history (Kriwet and Klug 2004), dating back to its original description by Woodward (1918), who indicated that this shark might have closer relationships to either squalomorphs (= “Spinacidae”) or batoids, which resulted in attempts to synonymise the genus with contemporaneous batoids like Belemnobatis sismondae Thiollière, 1852 (e.g., Maisey 1976). Recently, Jambura et al. (2023) re-analysed the systematic position of this shark, placing it within the Squalomorphii and suggesting a possible close relationship with Squatiniformes and Pristiophoriformes. However, for the moment there is a general uncertainty regarding the phylogenetic relationships of Protospinax (Jambura et al., 2023). While most studies of Protospinax are based on morphological analyses of skeletal remains (e.g., Schaeffer 1967; Maisey 1976; Carvalho and Maisey 1996; Jambura et al. 2023), little attention has been given to its dentition. Furthermore, numerous specimens do not allow a clear analysis of the dental pattern of Protospinax because teeth are poorly exposed or absent (Fig. 1). In the counterpart of the holotype of Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (NHMUK PV P 8775), only a few teeth are visible and deeply embedded in the matrix, as only the dorsal side of the skeleton is exposed (Fig. 1A). Another very well and completely preserved specimen (SNSB-BSPG 1963 I 19) is ventrally exposed but no dentition or individual teeth are preserved, which does not allow any detailed morphological analyses (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Holomorphic specimens of squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918, from Solnhofen (Germany), Tithonian (Upper Jurassic). A. Holotype NHMUK PV P 8775c. B. SNSB–BSPG 1963 I 19, overview (B1), close-up view of the head region (B2).

Here, we focus on associated and articulated dentitions of Protospinax annectans, which is the only species of the genus known from skeletal material, to present a detailed account of dental patterns and, in particular, to establish variations in tooth morphology to identify possible heterodonties. Furthermore, this study provides diagnostic dental characters for species of the genus Protospinax enabling us to re-evaluate the taxonomic status of tooth-based species. The specific goals of this study thus are to (i) present the first detailed account of dental characters in the type species Protospinax annectans, focusing on potential heterodonty patterns and (ii) re-assess the taxonomic validity of species previously assigned to Protospinax based on isolated teeth.

Institutional abbreviations.—JME-SOS, Jura-Museum Eichstätt, Germany; NHMUK, The Natural History Museum, London, UK; SMF, Senckenberg Naturmuseum Frankfurt, Germany; SMNS, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Germany; SNSB-BSPG, Staatliche Naturwissenschaftliche Sammlungen Bayerns-Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Munich, Germany; UM, Collection de Paléontologie de l’Université de Montpellier 2, France; WYDICE, Wyoming Dinosaur Center, Thermopolis, Wyoming, USA.

Other abbreviations.— D, labiolingual depth; W, mesiodistal width.

Nomenclatural acts.—This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in Zoobank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5035F9DC-F71E-4760-BF75-062CC54FA5B2.

Material and methods

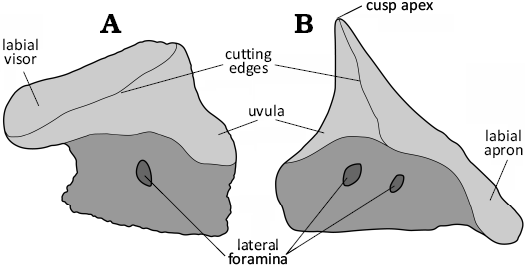

Terminology.—The description of elasmobranch teeth often involves the use of different descriptive terms for similar structures or characters, resulting in confusion about what these features represent. Many scholars use the terminology of Cappetta (1970, 2012) without a second thought. Here, however, we address specifically two terms for dental characters used in the scientific literature, i.e., the labial apron, and the labial visor. These terms have been used interchangeably or confusedly for referring to very different features (e.g., Cappetta 1987, 2012; Kriwet et al. 2009), or have been treated as synonyms (e.g., Cappetta 2012: 388; Villalobos-Segura et al. 2019: 5). However, in our opinion the labial apron and the labial visor can be adequately defined and distinguished from each other as two distinct dental features in elasmobranch teeth.

The labial visor is defined here as the labial part of the crown that extends labially (straight to slightly convex) over the labial root face without covering it (Fig. 2A). A labial visor is present, e.g., in the teeth of the sawshark Pristiophorus cirratus Latham, 1794 (e.g., Cappetta 2012: fig. 131K–O) or the extinct sclerorhynchoid sawfish Ptychotrygon ameghinorum Begat et al., 2023 (Begat et al. 2023: figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 2. Schematic illustration of the visor and the apron within elasmobranch teeth. A. Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (SMNS 89604/2); Mahlstetten (Germany), lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic). B. Nebrius obliquus Cappetta & Case, 2016 (UM-PAD 11); Andalusia (Alabama, USA), Lutetian (Eocene) (modified from Cappetta and Case 2016).

The labial apron, conversely, is defined here as the part of the crown that extends both labially and basally over the labial root face, is frequently convex in profile view, and coats at least a portion of the labial root face (Fig. 2B). A labial apron is present, e.g., in the tawny nurse shark Nebrius ferrugineus (Lesson, 1831) or the extinct rajiform Squatirhina cf. lonzeensis Casier, 1947 (see Herman et al. 1992: pl. 8).

An additional clarification needs to be presented, for the term labial protuberance, often used to describe an extension of the labial crown face protruding from the labial root face. This term has been used synonymously with both the labial visor and apron, respectively (e.g., Cappetta 2012; Cicimurri and Weems 2021; Dearden et al. 2025). However, as observed in Squatina squatina Linnaeus, 1758, and Cederstroemia triangulata Siverson, 1995, the term labial protuberance should be restricted to describing an extension of the labial crown face, that disrupts the outline of the labial crown edge only in a limited portion of the labial face, being. e.g., knob-like.

Another labial crown expansion referred to the labial peg is often used in lonchidiid sharks (e.g., Cappetta 2012; Manzanares et al. 2017). This character corresponds to a crown expansion of the labial face, which is mesiodistally narrow but well-expanded labially. Nonetheless, the structure is also referred to a labial protuberance (Rees and Underwood 2002) or a labial apron (Cappetta 2012). Regarding the similarity between the labial crown expansion of lonchiid and modern sharks (see above), we therefore support the use of labial protuberance for the labial crown extension that characterises lonchidiid shark teeth. The other global terminology used here follows that of Cappetta (2012).

The present study is primarily based on three partial skeletal remains, i.e., WYDICE-SOL-8007 (Fig. 3), JME-SOS 3386 (Fig. 4), NHMUK PV P 37014 (Fig. 5), which preserve portions of the dentition and allow for the reconstruction of the general dental pattern of Protospinax. These are complemented by information from newly discovered isolated teeth, SMNS 89604/1–9 and SMNS 89605/1–6 (Figs. 6, 7, 9). NHMUK P 37014 is the holotype of Squalogaleus woodwardi Maisey, 1976, which represents a junior synonym of Protospinax annectans (Carvalho and Maisey 1996).

While the three skeletal remains come from the Upper Jurassic Altmühltal Formation from Solnhofen (WYDICE-SOL-8007 and NHMUK 37014) and Eichstätt (JME-SOS 3386) quarries in Bavaria (SE Germany), the isolated teeth (SMNS 89604/1–9 and SMNS 89605/1) included here were recovered from marls exposed next to the street leading from Mahlstetten to Mühlheim South of Tübingen in Baden-Württemberg (SW Germany). These teeth are slightly older than those from Solnhofen as the marls are assigned to the Mutabilis Zone of the lower Kimmeridgian (Schweigert 2007; Klug 2009).

For documenting dental variations, specimen WYDICE-SOL-8007 was photographed using a Nikon D5300 DSLR camera with a mounted AF-S DX Micro NIKKOR 40 mm f/2.8G lens. Magnifications of teeth and scales of WYDICE-SOL-8007 were prepared with a Nikon D7500 DSLR camera with a mounted Laowa 25mm 2.8 2.5–5× Ultra-Macro lens or a mounted Plan 10 microscope lens. JME-SOS 3386 was photographed with a Panasonic Lumix DMC-G70 camera with a mounted Panasonic Lumix G Vario 12–32 mm f/3.5-G.6 ASPH lens. Close-ups of teeth of JME-SOS 3386 teeth were taken with a Sigma Olympus Macro 105 mm f/2.8G EX DG lens. Photos of the dentition of JME-SOS 3386 were stacked with the open-source software CombineZ, to extend the depth of field. NHMUK PV P 37014 was photographed using an Olympus OM-D E-M1 Mark II camera with a mounted M. Zuiko Digital ED 12–50 mm f/3.5-6.3G EZ lens. Close-ups of teeth of NHMUK PV P 37014 were prepared with a Laowa 25 mm 2.8 2.5–5× Ultra-Macro lens.

SMNS 89604/1–4 and 89605/1–4 from the lower Kimmeridgian of Mahlstetten representing isolated teeth were examined and photographed using a Scanning Electron Microscope (Cambridge Stereoscan 360 SEM) at the Museum of Natural History Berlin (Germany). The isolated teeth SMNS 89604/5–9, 89605/5 and 89605/6 were photographed with a 3D Keyence VHX-6000 microscope at the Department of Palaeontology (University of Vienna, Austria), using multi-lightning and stacking methods. All figures presented here were edited in Adobe Illustrator CC 2024.

Systematic palaeontology

Class Chondrichthyes Huxley, 1880

Subclass Elasmobranchii Bonaparte, 1838 sensu Maisey, 2012

Cohort Selachimorpha Nelson, 1984

Superorder Squalomorphii Compagno, 1973

Order Protospinaciformes Underwood, 2006

Family Protospinacidae Woodward, 1918

Genus Protospinax Woodward, 1918

Type species: Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918, Altmühltal Formation (lower Tithonian, Upper Jurassic), Solnhofen (Germany).

Species included: Protospinax carvalhoi Underwood & Ward, 2004b (Bathonian), Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (Callovian–Tithonian), Protospinax lochensteinensis Thies, 1982 (Oxfordian), and Protospinax planus Underwood, 2002 (Kimmeridgian).

Emended diagnosis.—Squalomorph sharks characterised by the following combination of dental features. Teeth small (up to 1 mm mesiodistal width) and bulbous, crown low with short to strongly reduced main cusp in adults, well-developed to reduced in juveniles, no lateral cusplets. Transversal crest dividing the crown into a broad, horizontal labial and a narrow, steep lingual crown faces, height of the visor reduced and protubes labially well above the root, labiobasal margin either rounded or slightly concave medially. Steep lingual crown face continued basally into a narrow, short uvula, two distinct margino-lingual root foramina present. Root lingually displaced with a flat basal face on which several small foramina open. Holaulacorhize root vascularization in juveniles, while hemiaulacorhize in anterior to antero-lateral teeth in adults. Teeth arranged in forming files in staggered rows, resulting in a crushing dentition. Dentition predominantly homodont, exhibiting a minor gradient monognathic heterodont pattern, in which tooth crowns remain low throughout the dentition, becoming more mesio-distally widened distally.

Remarks.—Based on the dental pattern displayed by holomorphic specimens and isolated teeth of Protospinax annectans, it is possible to re-assess the taxonomic validity of other species assigned to Protospinax. Accordingly, we identify three additional species that can be assigned to this genus in addition to P. annectans, based on the dental traits described above, i.e., Protospinax carvalhoi Underwood & Ward, 2004b, Protospinax lochensteinensis Thies, 1982, and Protospinax planus Underwood, 2002.

Teeth of Protospinax carvalhoi Underwood & Ward, 2004b, from the Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) of England differ from those of P. annectans in the presence of a (i) less mesio-distally widened tooth crown (W/D ratio of 0.82), (ii) strongly reduced to absent central cusp, (iii) the presence of a well-developed labial visor, and (iv) pentagonal- to hexagonal-like outline of the crown in occlusal view.

Teeth of P. lochensteinensis Thies, 1982, from the Oxfordian (Upper Jurassic) of Germany differ from those of P. annectans in the presence of a (i) sharp occlusal crest separating a flat and large labial and a shortened and steep lingual crown face, (ii) more pronounced tooth height and (iii) labiolingual extension, (iv) anterior teeth with a rounded appearance and (v) the presence of a short but pronounced vertical crest on the visor.

Teeth of P. planus Underwood, 2002, from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of England can be differentiated from P. annectans by (i) the poorly developed central cusp, (ii) its distinct transversal crest differentiating the lingual and the labial faces, and (iii) its rounded, massive root branches.

The three remaining species that were previously assigned to Protospinax, P. bilobatus Underwood & Ward, 2004b, P. magnus Underwood & Ward, 2004b, and P.? muftius Thies, 1982, all from the Middle Jurassic of England, do not display the characteristic dental features of Protospinax as outlined above, but rather those of Orectolobiformes and therefore are transferred to this order representing two new taxa based preliminarily on a well-developed, distinctive orectolobiform-like labial visor (see below).

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Toarcian (Lower Jurassic)–Valanginian (Lower Cretaceous); England, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Russia, and Spain.

Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918

Figs. 3–8.

1976 Belemnobatis annectans; Maisey 1976: 733, fig. 2.

1976 Squalogaleus woodwardi; Maisey 1976: 740, pl. 112: 8.

1982 Protospinax annectans; Thies 1982: 21–23, pl. 3.

1993 Protospinax annectans; Duffin 1993: 3, fig. 2.

2013 Protospinax sp.; Klug and Kriwet 2013: 246–247, fig. 4.

Emended diagnosis.—A species of Protospinax characterised by the following dental features (for skeletal characters see Jambura et al. 2023). Anterior teeth only slightly mesio-distally widened with a W/D ratio of ca. 1.5. Antero-lateral teeth relatively mesio-distally wider than anterior teeth with W/D ratio of 2.2–2.5. Latero-posterior and commissural teeth between anterior and antero-lateral teeth with a W/D ratio of ca. 2.0. Anterior to antero-lateral teeth with small, but well-developed central cusp. No lateral cusplets. Transversal crest weakly developed. Height of the visor of the labial face reduced and jutting out well above the root in anterior tooth files, on a short distance with distal tooth files. Anterobasal crown margin convex, can be medially concave. Tooth crown oval in occlusal view and devoid of any ornamentation. Root low with thin root branches with rounded extremities, hemiaulacorhize in anterior teeth, holaulacorhize in lateral positions.

Material.—Three holomorphic spécimens (WYDICE-SOL -8007, JME-SOS 3386, NHMUK PV P 37014 ) from the Tithonian (Upper Jurassic) of Solnhofen (Germany), nine figured teeth (SMNS 89604/1–9) and 341 unfigured teeth (SMNS 89604/10, lot number) from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of Mahlstetten (SW Germany).

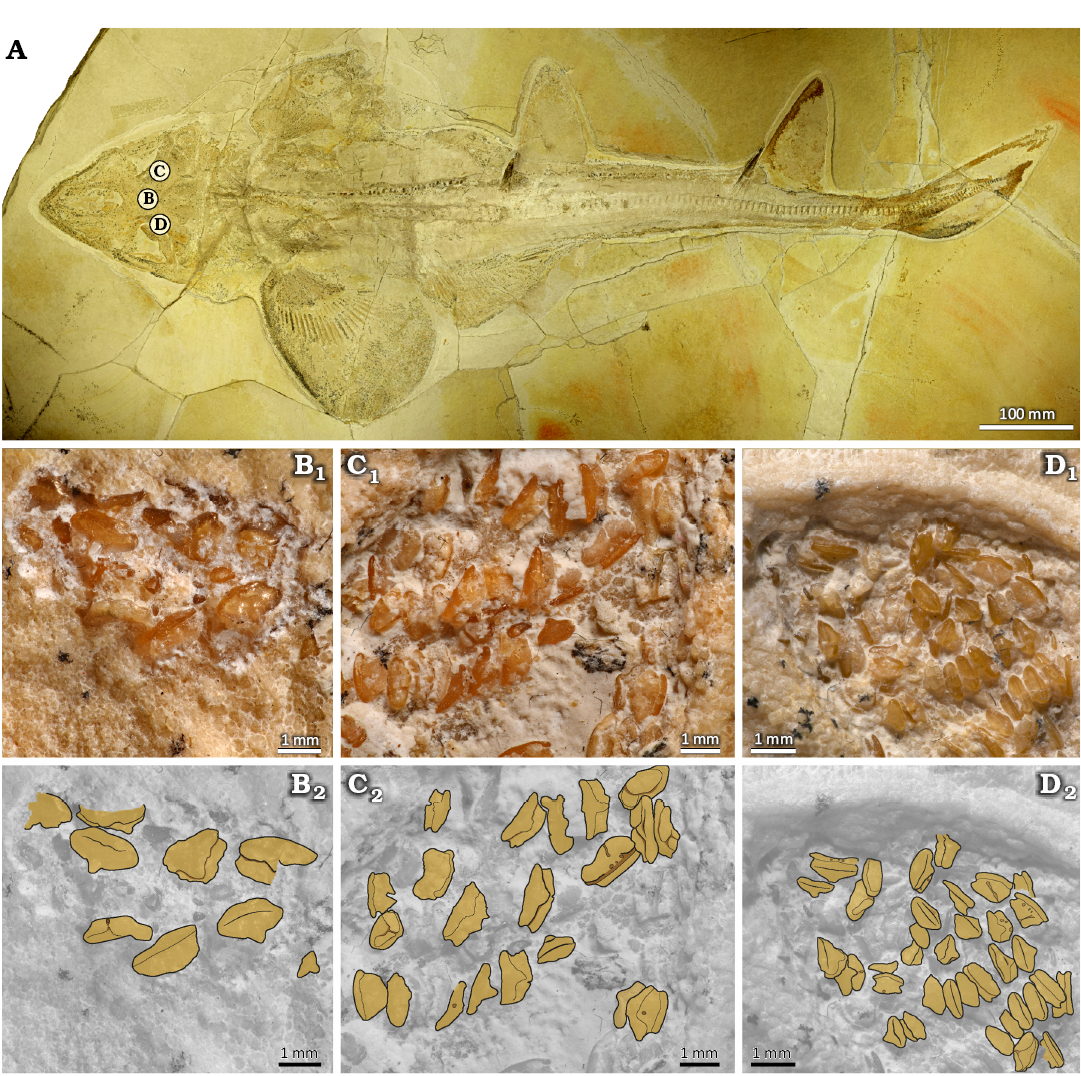

Description.—WYDICE-SOL-8007 (Fig. 3): This specimen represents an almost complete skeleton of an adult female, exposed in dorsal view (Fig. 3A). The dentition is partially preserved, with only the posterior teeth of the palatoquadrates being accessible (Fig. 3B–D), whereas only anterior to posterior teeth are preserved in their original position on the Meckel’s cartilage (Fig. 3B, C), with several lateral and posterior teeth exposing labiolingual fractures (Fig. 3D).

A significant portion of the anterior teeth unfortunately is still embedded in the matrix, preventing identification of all features (Fig. 3B). However, the few exposed anterior teeth nevertheless allow the assessment of their general morphology. They are mesio-distally widened with a reduced height of the visor (Fig. 3B). A weak transversal crest separates the narrow, steep lingual from the broader labial crown face, both of which lack any ornamentations. Centrally, the transversal crest rises to form a small and low, but acute central cusp (Fig. 3B1). Lingually, a narrow, basally pointed uvula is developed.

The vascularization of anterior tooth roots corresponds to the hemiaulacorhize type (sensu Cappetta 2012) with linguo-medially fused, but labiolingual diverging root branches forming a broad V-shaped labial depression. The extension of the labial foramen creates a depression in the lingual outline in basal view between the two root branches.

Lateral teeth are mesio-distally wider than anterior ones, with slightly more elevated transverse crests that form a distinct central cusp (Fig. 3C). No lateral cusplets are present. Lateral to latero-posterior teeth display a well-developed nutritive groove that separates mesiodistally wide root lobes. The development of this groove varies and is not completely open in all teeth. In some cases, it is closed labially, where several horizontally arranged foramina are visible on the upper labial root face below the crown (Fig. 3C).

Posterior teeth (Fig. 3D) display a similar morphology to lateral teeth but can be differentiated from the latter by a very reduced main cusp and a labiolingually narrower tooth crown.

Fig. 3. Holomorphic adult specimen of squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (WYDICE-SOL-8007) from Solnhofen (Germany), lower Tithonian (Upper Jurassic). A. Specimen overview. B. Anterior teeth in central position of the jaw. C. Anterior to lateral teeth of the right Meckel’s cartilage D. Lateral to commissural teeth of the left Meckel’s cartilage. B1–D1 photographs; B2–D2, drawings.

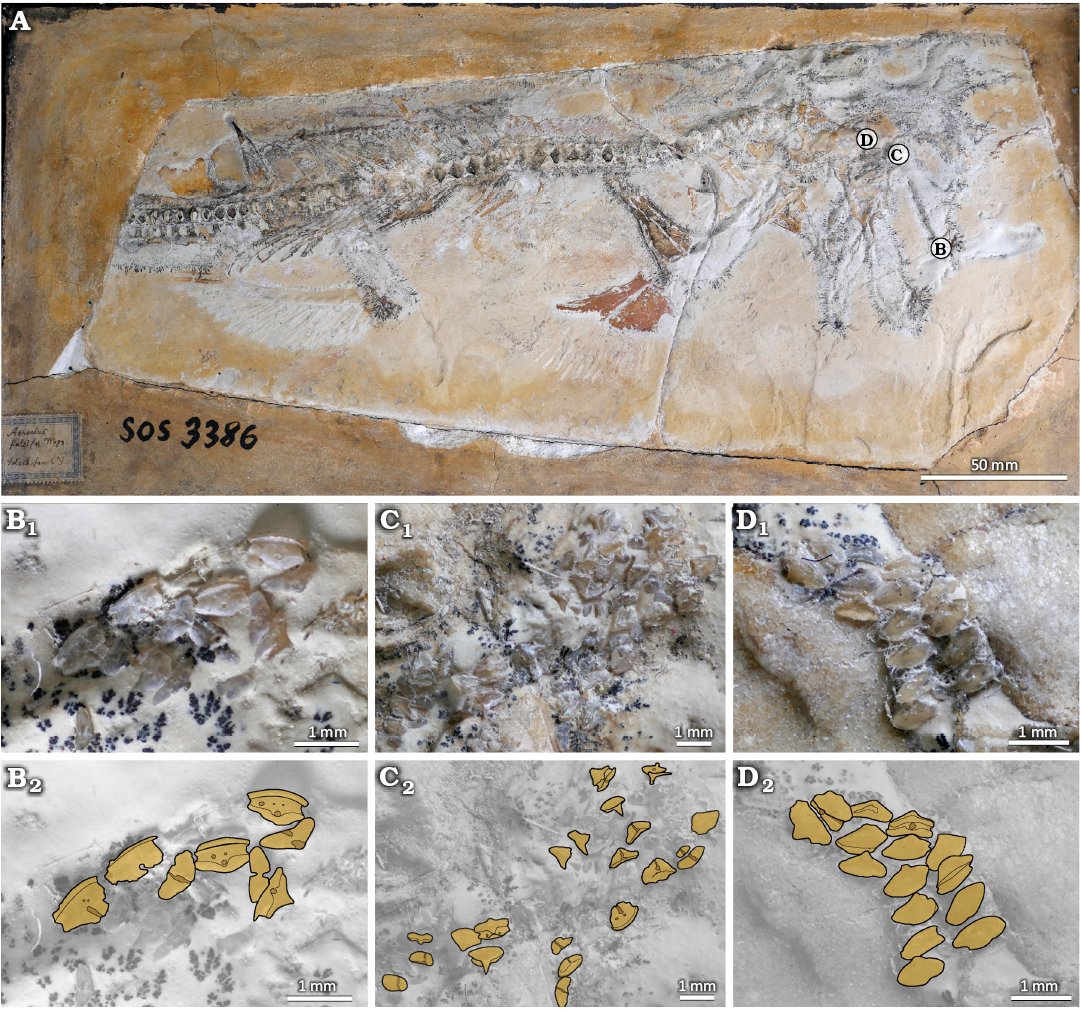

JME-SOS 3386 (Fig. 4): This specimen represents a small, incomplete skeleton of a supposedly juvenile female, ca. 30 cm in length, preserved in latero-dorsal view. Numerous teeth are preserved on the anterior portion of the palatoquadrate, which is detached from the remaining cranial elements due to taphonomic processes (Fig. 4A). Teeth of the Meckel’s cartilage either are not preserved or still completely covered by matrix.

Teeth of anterior files are mesio-distally widened with a rather short labial crown face in profile view. The lingual face is very reduced and short (Fig. 4B). A small central cusp seemingly is present, although it cannot be fully discerned due to the occlusal crown face still being covered partially with sediment.

The root is labiolingually compressed and slightly displaced lingually so that the crown juts out labially over the root, while the root is slightly visible lingually in occlusal view. The root is of the hemiaulacorhize vascularization type and arc-shaped in labial, but concave in basal views.

The labial face of the root displays a basally centrally positioned foramen, which is connected to the central labial root foramen. An additional row of foramina opens along the labial root face below the crown, and a pair of margino-lingual foramina is developed (Fig. 4B).

The antero-lateral teeth display a similar morphology with those of the anterior rows. However, the antero-lateral ones slightly differ in their root vascularization, which is of the holaulacorhize type (sensu Cappetta 2012). It is expressed here by a shallow nutritive groove, which separates the root in two triangular root lobes when observed basally, and a centrally positioned foramen (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, several teeth present a strongly developed, pointed cusp that marks an obtuse angle between the labial and lingual oral faces in profile view.

Although similar in morphology, the lateral and commissural teeth can be distinguished from anterior and antero-lateral teeth by their less-pronounced cusp that is displaced distally in some more posterior teeth (Fig. 4D). Two incipient pronounced cutting edges, each separated from the central cusp by a moderately expressed notch, may occur. A detailed observation of the root in commissural teeth, however, is not possible, because most are embedded in sediment, while others that expose the root are too poorly preserved.

Fig. 4. Holomorphic juvenile specimen of squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (JME-SOS 3386) from Solnhofen (Germany), lower Tithonian (Upper Jurassic). A. Specimen overview. B. Anterior teeth of the palatoquadrate. C. Anterior to lateral teeth of the palatoquadrate. D. Commissural teeth. B1–D1 photographs; B2–D2, drawings.

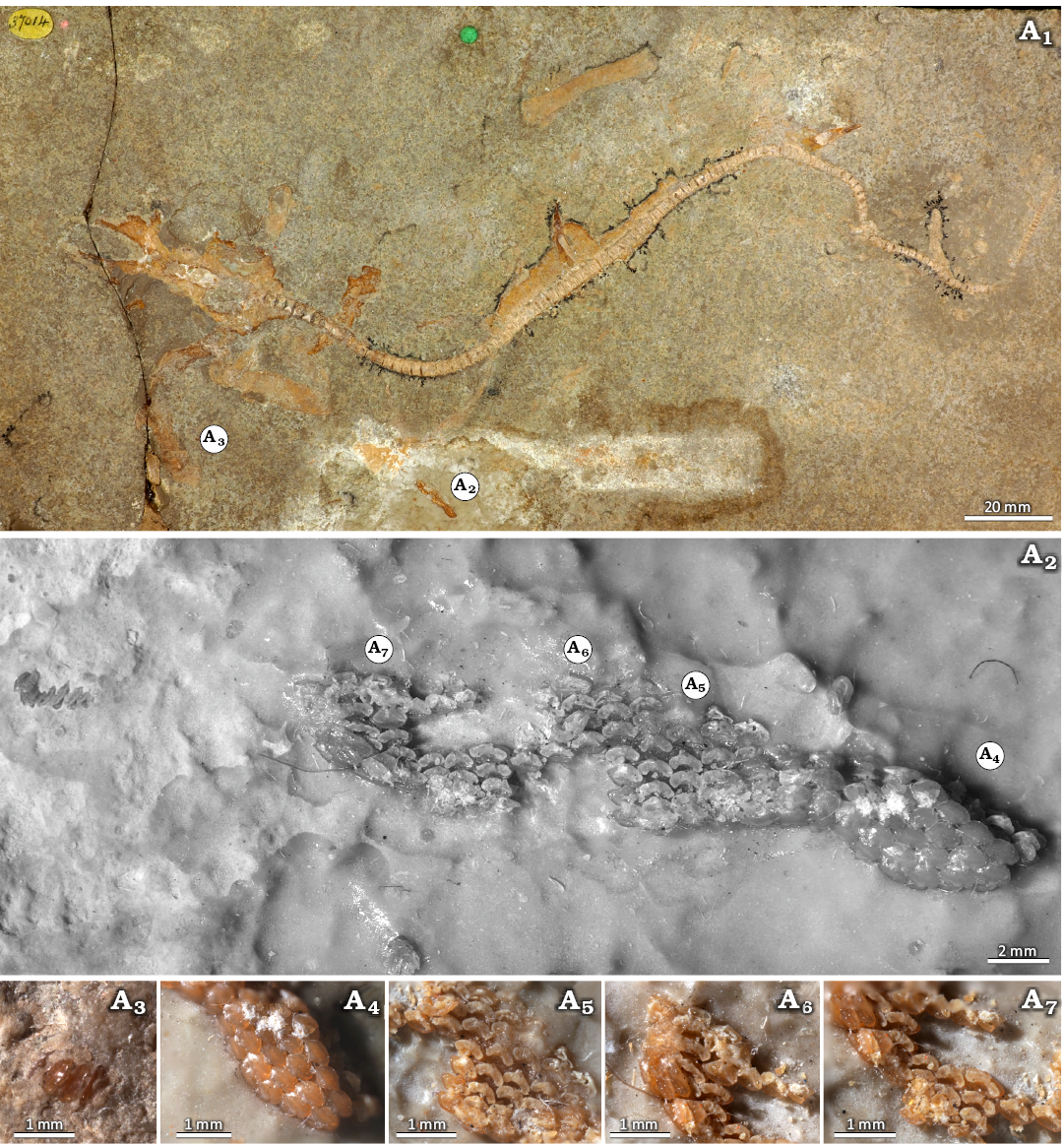

NHMUK P 37014 (Fig. 5): The specimen represents a small, incomplete skeleton of about 280 mm length and of an unidentified sex due to absence of a well-preserved pelvic region (Fig. 5A1). Similarly to JME-SOS 3386, an associated dental set is detached from the head region (Fig. 5A2). These teeth could represent part of the palatoquadrate dentition. The anteriormost teeth are preserved separately from the tooth cluster, well-embedded in the sediment matrix but slightly exposed in occlusal-lingual view (Fig. 5A3). The teeth are mesio-distally widened, the main cusp is short and rounded in cross-section and the lateral edges of the crown are weakly raised. The labial face is expanded and forms a convex visor.

The anterior files of the dentition are occlusally exposed and arranged in staggered rows (Fig. 5A4). The teeth are mesio-distally widened with a well-developed labial crown face, which displays a developed and rounded visor. The main cusp is low and rounded. The lingual crown face is narrow and steep, with slightly elevated lateral edges.

Next to the anterior teeth, the basal root face of the antero-lateral teeth is exposed, while one set of teeth had previously been extracted, resulting in a shallow pit; the whereabouts of these teeth is unknown (Fig. 5A2, A5). The antero-lateral teeth are mesio-distally expanded, and the exposed crown displays a reduced labial crown face in comparison with anterior teeth. The root is arc-shaped with root branches that are fused and are of the hemiaulacorhize vascularization type (Fig. 5A5). A shallow nutritive groove that separates the root branches begins to appear with the most distally positioned antero-lateral teeth, associated with an enlargement of the centro-lingual foramen of the root.

Lateral teeth present an additional artificial extraction scar in the lower centre of the tooth files (Fig. 5A6). Basally exposed, the teeth are notably mesio-distally expanded, the root branches are separated by a completely developed nutritive groove representing the holaulacorhize root vascularization type.

Despite mainly exposing the basal root face, some posterior teeth are visible in occlusal view (Fig. 5A7). They display generally a very similar morphology to lateral teeth, but the main cusp is very reduced.

Fig. 5. Holomorphic specimen of squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 (NHMUK PV P 37014) from Solnhofen (Germany), lower Tithonian (Upper Jurassic). Specimen overview (A1). Teeth detached from the jaws, overview (A2), close-up views of anterior files (A3, A4), antero-lateral (A5), lateral (A6), and commissural (A7) teeth.

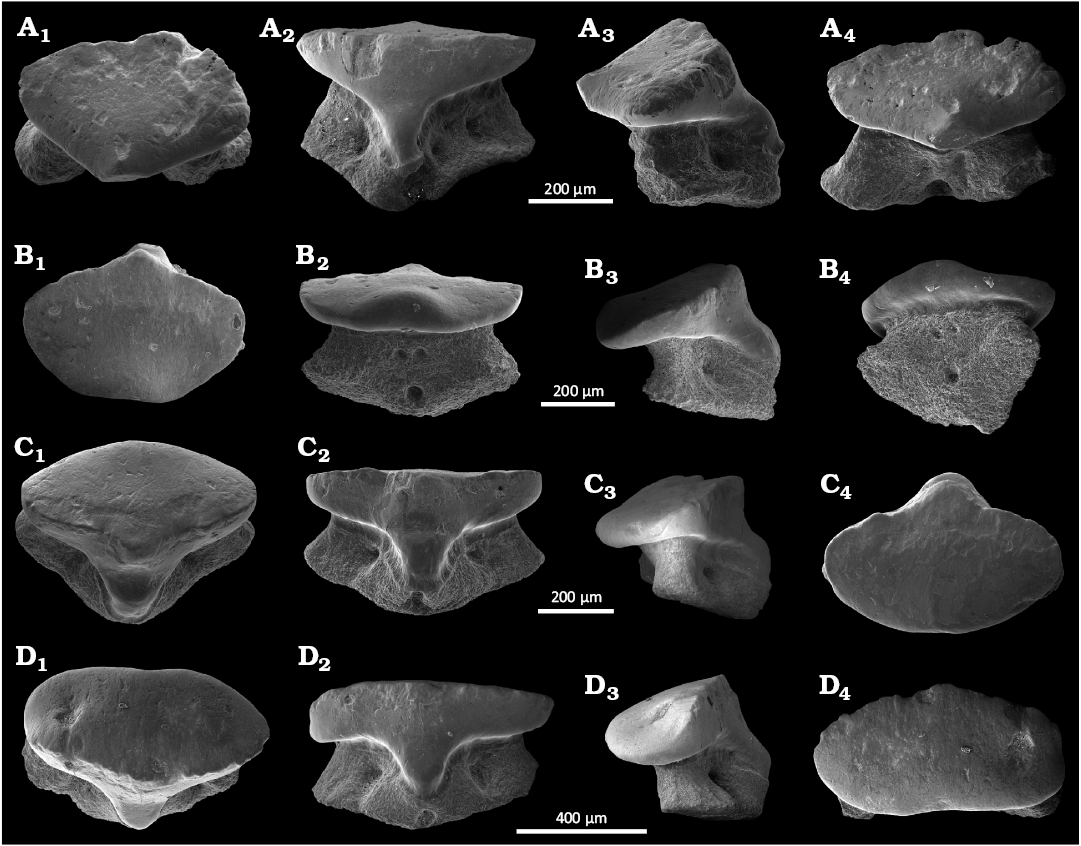

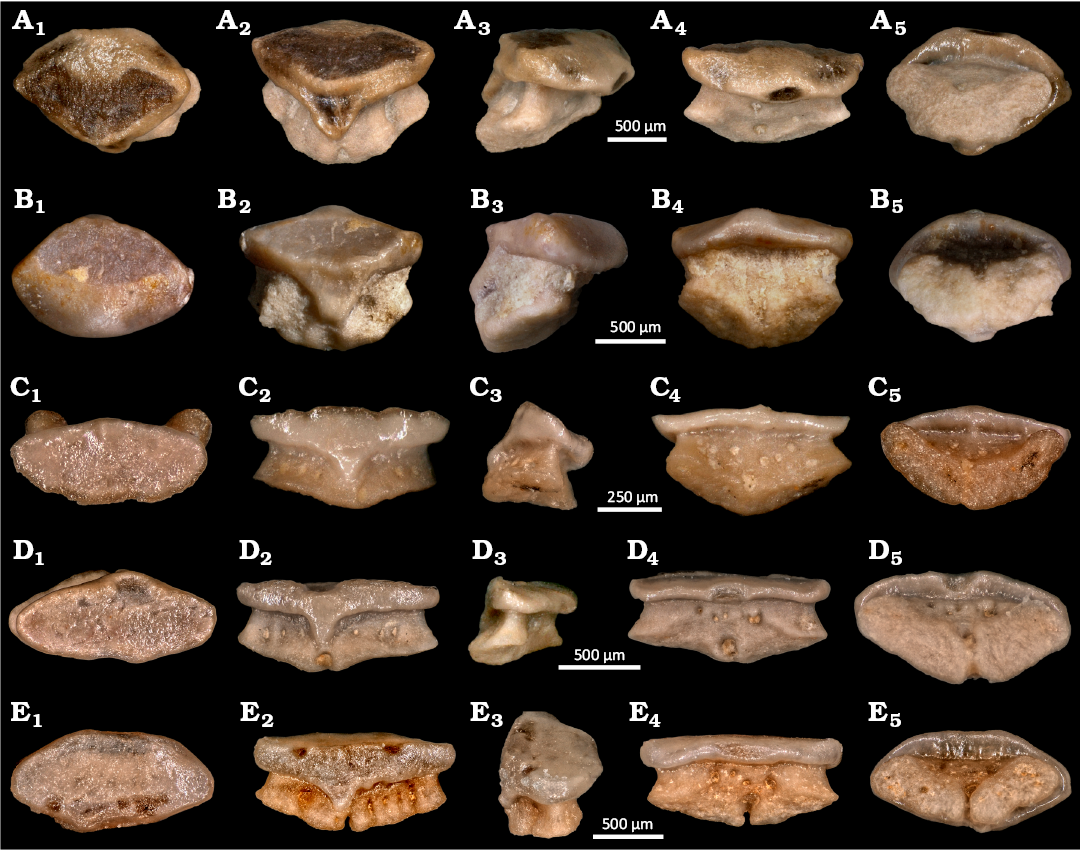

SMNS 89604/1–9 (Figs. 6, 7): 350 isolated teeth from the locality of Mahlstetten (lower Kimmeridgian) in Baden-Württemberg (SW Germany) can be unambiguously assigned to Protospinax annectans based on their characteristic morphologies. These teeth provide additional morphological details such as the root vascularization type (Figs. 6, 7), which is often covered by matrix in holomorphic specimens. The position of the isolated teeth within the jaws was determined through detailed comparisons with the dentitions of holomorphic specimens, using the ratio between tooth crown depth and tooth crown width in occlusal view (see Figs. 3–5).

The anterior teeth exhibit a W/D ratio of 1.5 (Figs. 6A, B, 7A, B) and have a low crown with a blunt transversal cutting edge that rises centrally into a very low, lingually inclined cusp. In occlusal view the crown has a rhomboidal outline, while in anterior view, it presents a short, broadly rounded protuberance with a straight basal margin (broken in the specimen SMNS 89604/5 figured in Fig. 7A). Laterally, the height of the crown labial face is reduced, and labiobasally inclined (Fig. 7A3, B3). It appears straight to even slightly concave in lateral view and slightly undulating with weakly raised lateral edges in anterior view (Figs. 6B2, B4, 7A4, B4). The lingual face is highly reduced and terminates abruptly in a broadly triangular lingual uvula that extends a short distance onto the lingually displaced root (Fig. 6A2, A3). The root exhibits a hemiaulacorhize vascularization, with the root lobes forming a shallow anterior (labial) depression (Fig. 7A5, B5). In labial view, the basal surfaces of the root lobes are oblique. A comparably large foramen opens centrally into the labial concavity and connects with the centro-lingual foramen of the root (Fig. 7B5). Additional smaller foramina are present on the labial root face just below the crown (Figs. 6B2, B4, 7A4). A pair of margino-lingual foramina open into deep, vertically oriented slit-like groves (Figs. 6A2, A3, 7A2, A3, B2, B3).

Fig. 6. SEM photographs of the teeth of squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918, from Mahlstetten (Germany), lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic). A. SMNS 89604/1 anterior tooth in occlusal (A1), lingual (A2), lateral (A3), and labial (A4) views. B. SMNS 89604/2 anterior tooth in occlusal (B1), labial (B2), lateral (B3), and labio-basal (B4) views. C. SMNS 89604/3 antero-lateral tooth in linguo-occlusal (C1), lingual (C2), lateral (C3), and occlusal (C4) views. D. SMNS 89604/4 lateral tooth in linguo-occlusal (D1), lingual (D2), lateral (D3), and occlusal (D4) views.

The antero-lateral teeth exhibit a W/D ratio of about 2.2 (Figs. 6C, 7C) and are mesio-distally wider than the anterior teeth. The tooth crown is low and unequally divided into a larger labial and a smaller lingual face by a weakly developed transversal crest (Figs. 6C3, 7C3). This crest forms an incipient central cusp, giving the crown a slightly higher appearance than that of the anterior teeth (Fig. 6C4). In lateral view, the crown is convex, and projects slightly labially above the root, unlike in anterior teeth (Figs. 6C3, 7C1). In occlusal view, the crown is oval with a very small, reduced labial protuberance, and a short, narrow lingual uvula (Figs. 6C4, 7C3). The root is less lingually displaced than in anterior teeth and exhibit a less pronounced hemiaulacorhize vascularization. In basal view, the root is arc-shaped with rounded lobe extremities (Fig. 7C5). The labial depression is broader and presents a row of irregular foramina above a small, basally placed centro-labial foramen on the labial root face (Fig. 7C4). The centro-lingual foramen also is small, with up to three pairs of margino-lingual, circular foramina.

Fig. 7. Numerical microscope pictures of the teeth of squalomorph shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918, from Mahlstetten (Germany), lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic). A. SMNS 89604/5 anterior tooth. B. SMNS 89604/6 anterior tooth. C. SMNS 89604/7 antero-lateral tooth. D. SMNS 89604/8 lateral tooth. E. SMNS 89604/9 lateral tooth. A1–E1, occlusal views; A2–E2, lingual views; A3–E3, lateral views; A4–E4, labial views; A5–E5, basal views.

The lateroposterior and commissural teeth exhibit a W/D ratio of 2.2 (Figs. 6D, 7D, E) and are mesio-distally widened and slightly smaller than lateral teeth. Overall, these teeth are more robust, and lower than anterior and antero-lateral teeth, presenting an incipient, slightly elevated central cusp that diminishes in more distally located teeth. In occlusal view, the crown is sub-oval (Figs. 6D4, 7D1). In both latero-posterior and commissural teeth, the labial protuberance is very short and mesially displaced (Figs. 6D3, D4, 7D3, D4). Several pairs of margino-lingual foramina are developed (Fig. 7D4, E4). In commissural teeth, the protuberance can even be completely reduced (Fig. 7E3, E4). The teeth of both positions present a narrow and short lingual uvula (Figs. 6D2, 7D2, E2). The root lobes are lingually displaced and labial root depression is shallow. An irregular row of foramina is present on the labial root face above the depression (Fig. 7D5, E5). The connecting canal between the labio- and linguo-central foramina opens gradually distally forming a narrow nutritive groove that separates the root lobes (Fig. 7D4, D5, E4, E5).

Remarks.—For an extended literature list of Protospinax annectans skeletal material, see Jambura et al. (2023).

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Toarcian (Lower Jurassic) to Valanginian (Lower Cretaceous).

Superorder Galeomorphii Compagno, 1973

Order Orectolobiformes Applegate, 1972

Family indet.

Genus Jurascyllium nov.

Zoobank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:C2371D41-5A3B-4B0E-8447-52C120BE286A.

Etymology: From the Jurassic period and the genus name Scyllium, itself from the ancient Greek σκύλιον (skúlion), small shark.

Type species: Protospinax magnus Underwood & Ward, 2004b, from Watton Cliff, Southern England (Bathonian, Middle Jurassic).

Species included: Type species only.

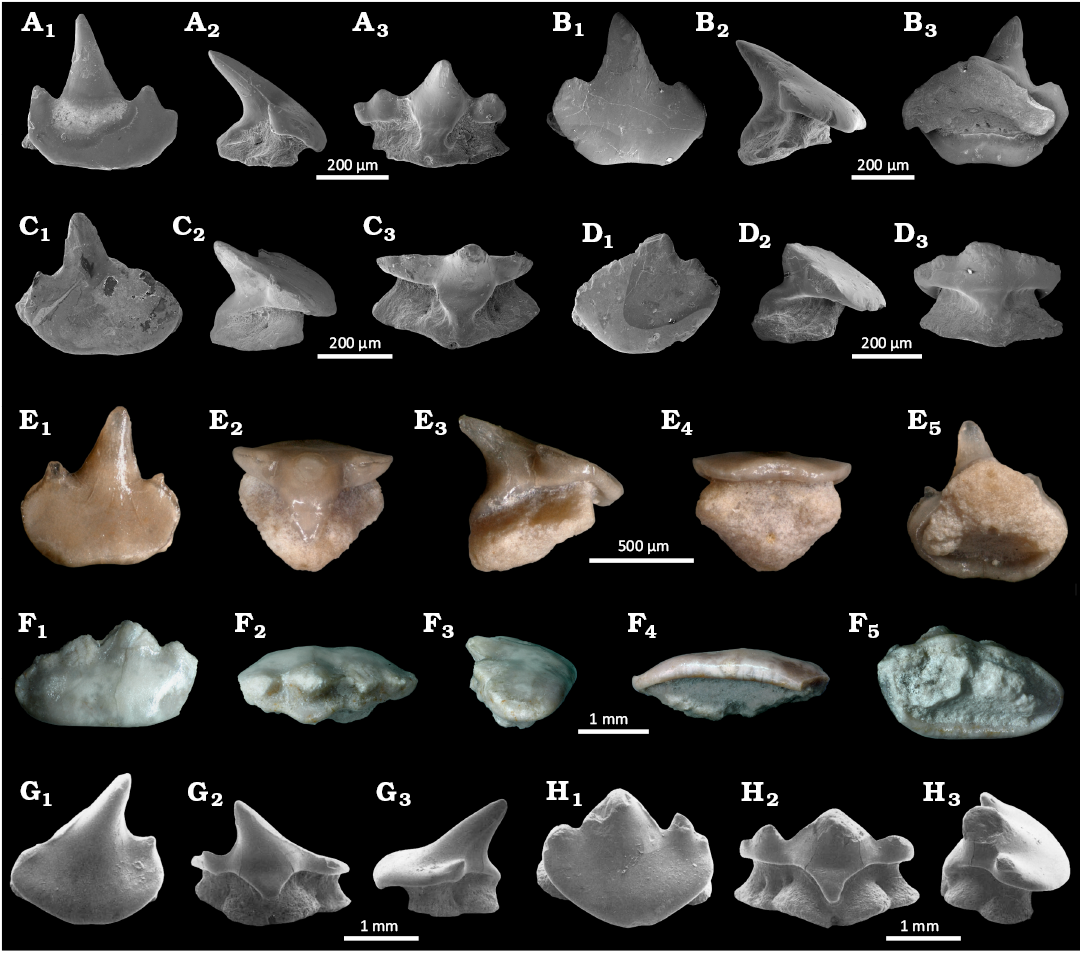

Diagnosis.—An orectolobiform shark characterised by a moderately heterodont dentition defined by (i) cuspidate and mesio-distally widened anterior teeth, (ii) well-developed, high and lingually inclined main cusp, (iii) up to two pairs of small upright lateral cusplets, (iv) continuous cutting edges that extend between main cusp and lateral cusplets before forming an acute apex, (v) well-developed labial visor with rectilinear to slightly concave labial margin, (vi) well-developed but flat uvula flanked by up to three pairs of margino-lingual foramina, and (vii) two labially divergent root branches that meet lingually in adult specimens (hemiaulacorhize root vascularization pattern), while the root branches are laterally concave. Juvenile teeth characterised by hemiaulacorhize or holaulacorhize vascularization. Antero-lateral teeth differ from anterior ones in a reduction of lateral cusplets and by a less-developed main cusp that is inclined lingually. Lateral teeth are more mesio-distally widened with smaller main cusp and without lateral cusplets.

Remarks.—In order to provide a more robust support for Jurascyllium gen. nov., a comparison will be made here between Jurascyllium gen. nov. with teeth of Protospinaciformes and Orectolobiformes, which share similar tooth morphologies.

Teeth of Protospinax Woodward, 1918, can be differentiated from those of Jurascyllium gen. nov. by the absence of lateral cusplets, the shortened labial face, the lower central cusp and the obtuse angle between cusp and oral face.

Teeth of Chiloscyllium Müller & Henle, 1837, can be distinguished from those of Jurascyllium gen. nov. by the strongly developed and wide main cusp that occupies more than 2/3 of the crown width, the single pair of poorly pronounced lateral cusplets, the more developed lingual uvula, the more acute angle between the root branches, a wide nutritive groove. Teeth of Palaeobrachaelurus Thies, 1982, differ from those Jurascyllium gen. nov. by the presence of a mesiodistally narrow and labiolingually shortened labial apron, lateral cusplets that are more divergent and less juxtaposed to the main cusp and a very narrow uvula.

Teeth of Heterophorcynus Underwood & Ward, 2004b, can be differentiated from those of Jurascyllium gen. nov. by the mesio-distally constrained tooth, a strongly elongated labial visor, short and divergent lateral cusplets and an elongated uvula.

Historically, Protospinax magnus and Protospinax bilobatus from the Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) of England were attributed to Protospinax (Underwood and Ward 2004b). Both species share very similar tooth morphologies and are characterised by a heterodont dentition with anterior and antero-lateral teeth possessing a prominent, well-developed lingually inclined main cusp and flanked by two pairs of lateral cusplets. The outermost pair varies from very reduced to incipient. Labially, the visor significantly overhangs the root and, in some teeth, displays a poorly pronounced central concavity.

According to Underwood and Ward (2004b) both species can be differentiated by their size, with P. magnus teeth being twice as large as those of P. bilobatus. Additionally, the two species allegedly differ in tooth root vascularization type, with P. magnus exhibiting the hemiaulacorhize stage whereas tooth vascularization in teeth of P. bilobatus is holaulacorhize.

Underwood (2004) suggest that P. magnus and P. bilobatus occupied different environments across the Bathonian of southern England with P. magnus being abundant in open marine settings, while P. bilobatus was constricted to protected marine settings. However, these notable palaeoecological differences, may reflect ontogenetic shifts within the same species, where adults occupied open marine environments while juveniles inhabited protected environments with low predation risk (nursery areas), a pattern known in various extant and extinct elasmobranchs (Castro 1993; Duncan and Holland 2006; Pimiento et al. 2010, Landini et al. 2017; Villafaña et al. 2020).

Considering the high morphological similarities of their crowns and the shifts in vascularization patterns seen in the taxa reviewed in the present study (P. annectans and various orectolobiforms) we find insufficient evidence to justify the presence of two species. Consequently, in accordance with Article 23.3 and subarticle 23.3.2.2 of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN 1999), P. bilobatus represents a junior synonym of P. magnus.

A similar pattern is present in several species of the extant orectolobiform genera Chiloscyllium, Brachaelurus, or Stegostoma, where the broad labial crown face may be regularly convex or slightly indented medially depending on the tooth position within the jaw (Ogilby 1906; Müller and Henle 1837, 1838; Herman et al. 1992; Cappetta 2012). In addition, several extinct orectolobiforms, such as Delpitoscyllium, Plicatoscyllium, and Heterophorcynus present an intermittent central concavity on their labial extension, seemingly influenced by the tooth position within the jaws and ontogenetic stage (Case and Cappetta 1997; Noubhani and Cappetta 1997; Underwood and Ward 2004b; Cappetta 2012). The lateral teeth are characterised by a crown with an oval outline and a developed cusp, but less pronounced than with the anterior ones, which can be mesiodistally displaced.

Conversely to P. magnus, the dentition of Protospinax annectans differs markedly in its homodont pattern (see above), with teeth completely lacking lateral cusplets in both juvenile and adult stages (only incipient ones may be present). Furthermore, the main cusp in adult P. annectans teeth is significantly lower and broader compared to those of P. magnus. These pronounced differences support our interpretation that P. magnus is not a member of the protospinaciform, but instead an orectolobiform shark. Consequently, we introduce the new genus, Jurascyllium gen. nov. for this species.

Most extant and extinct orectolobiforms, apart from parascyliids, bear a mesiodistally broad labial face that extends over the root and forms an apron or a visor (Herman et al. 1992; Cappetta 2012). The morphology of this visor is quite different from what is seen in teeth of other sharks having a labial visor, such as heterodontiforms and protospinaciforms.

It should be noted that in stem parascyliids such as Pararhincodon, the labial crown face is concave but presents a centrally positioned and low labial protuberance, as demonstrated by Dearden et al. (2025). This dental feature may result from the reduction of the broad labial crown face and represent a plesiomorphic feature of their dentitions. This, conversely, implies that the presence of a concave labial crown and the absence of labial protuberance represent a synapomorphic feature. Consequently, we are confident that a distinct labial visor represents a symplesiomorphy of orectolobiform teeth. Additionally, the root is lower in the new taxon described here and lingually extended below the uvula in teeth of orectolobiforms, while in protospinaciforms the root is higher, more rectangular in lateral view and generally not extended below the uvula. Moreover, protospinaciform teeth always lack developed lateral cusplets. These features in addition with the high central cusp and the presence of marked lateral cusplets in all teeth allow us to assign these teeth to a species belonging to the new genus, Jurascyllium gen. nov. and place it within Orectolobiformes, but with uncertain systematic position within the order.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Bathonian (Middle Jurassic)–lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic), from South-eastern England and south-western Germany.

Jurascyllium magnum (Underwood & Ward, 2004b) comb. nov.

Fig. 8A–F.

1993 Protospinax annectans; Duffin 1993: 3, fig. 3.

2004 Protospinax magnus; Underwood and Ward 2004b: 483, pl. 11: 1–15.

2004 Protospinax sp. 1; Underwood and Ward 2004a: fig. 5H–J.

2004 Protospinax bilobatus; Underwood and Ward 2004b: 484, pl. 12: 1–12.

2004 Protospinax 2; Underwood and Ward 2004a: fig. 5K–M.

2015 Protospinax magnus; Delsate and Felten 2015: fig. 6.

2015 Protospinax bilobatus; Delsate and Felten 2015: fig. 6.

Material.—38 teeth (SMNS 89605/1–7) from the lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of Mahlstetten, SW Germany.

Description.—The anterior teeth (SMNS 89605/1–2 and 89605/5, Fig. 3A–B, E) are characterised by a well-developed main cusp, flanked by one or two pairs of short and robust lateral cusplets (Fig. 8A, B). The apron is relatively short but mesiodistally extended, while a slightly pronounced concavity can be observed in the apron centre (Fig. 8M). The illustrated antero-lateral tooth (Fig. 8C) is rather similar to the anterior ones but slightly differs by a shortened and non-centred main cusp, which is associated with reduced lateral cusplets. The lateral teeth differ by very reduced main cusp and vestigial lateral cusplets, while the teeth can be mesiodistally elongated (Fig. 8F). This taxon is known from 41 isolated teeth recovered from the locality of Mahlstetten (lower Kimmeridgian) in Baden-Württemberg (SW Germany) in addition to those of South England. The Mahlstetten teeth can be unambiguously assigned to Jurascyllium magnum (Underwood & Ward, 2004b) (Fig. 8A–F) by the combination of the following characters: the anterior teeth are characterised by a well-developed main cusp flanked by one or two pairs of short and robust lateral cusplets (Fig. 8A, B, E). The visor is relatively short but mesio-distally extended, while the labial visor margin is slightly concave centrally (Fig. 8E1). The antero-lateral tooth (Fig. 8C) is rather similar to the anterior ones but with a shortened and non-centred main cusp and reduced lateral cusplets.

The lateral teeth (SMNS 89605/4 and 89605/6, Fig. 3D, F) are distinguished by a very reduced main cusp and vestigial lateral cusplets. These teeth can be either mesio-distally widened (Fig. 8F) or exhibit a relatively developed, rounded visor (Fig. 8D1).

Fig. 8. The teeth of orectolobiform sharks Jurascyllium magnum (Underwood & Ward, 2004a) (A–F) from Mahlstetten (Germany), lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) and Archaeoscyllium muftium (Thies, 1982) (G, H) from South England, Callovian (Middle Jurassic) (modified from Thies 1982). A. SMNS 89605/1 anterior tooth, in occlusal (A1), lateral (A2), and lingual (A3) views. B. SMNS 89605/2 anterior tooth, in occlusal (B1), lateral (B2), and basal (B3) views. C. SMNS 89605/3 antero-lateral tooth, in occlusal (C1), lateral (C2), and lingual (C3) views. D. SMNS 89605/4 lateral tooth, in occlusal (D1), lateral (D2), and lingual (D3) views. E. SMNS 89605/5 anterior tooth, in occlusal (E1), lingual (E2), lateral (E3), labial (E4), and basal (E5) views. F. SMNS 89605/6 lateral tooth, in occlusal (F1), lingual (F2), lateral (F3), labial (F4), and basal (F5) views. G. SMF 7112 anterior tooth, in occlusal (G1), lingual (G2), and lateral (G3) views. H. SMF 7113 lateral tooth, in occlusal (H1), lingual (H2), and lateral (H3) views. A–D and G, H, SEM photographs; E, F, numerical microscope pictures.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) to lower Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic), from south-eastern England and south-western Germany.

Genus Archaeoscyllium nov.

Zoobank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:FD0C4C5A-3140-4A30-825 D-6BDFA0352AA1.

Etymology: From the ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaîos), ancient; and the genus name Scyllium, itself from ancient Greek σκύλιον (skúlion), small shark.

Type species: Protospinax? muftius Thies, 1982; Rookery Pit, SE England, Callovian (Middle Jurassic).

Species included: Type species only.

Diagnosis.—Teeth with wide and well-developed labial visor, slightly concave medially. Cutting edge well-developed, forming a distinct and well-developed main cusp. Main cusp in anterior-most teeth distinctly inclined distally, anterior-most teeth with only a single distal cusplet. Lateral teeth with a pair of small lateral cusplets, positioned on the lateral crown shoulders, incipient additional pair of lateral cusplets might be developed. Lateral cusplets in latero-posterior teeth reduced. Hemiaulacorhize-type root vascularization with more than a single pair of margino-lingual foramina.

Remarks.—In order to provide a more robust support for Archaeoscyllium gen. nov., a comparison will be made here between Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. with teeth of Protospinaciformes and Orectolobiformes, which share similar tooth morphologies. Teeth of Protospinax Woodward, 1918, can be differentiated from those of Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. by the absence of lateral cusplets, the smooth crown lingual face with a less-rounded labial visor, the wider lingual uvula, and the lack of a well-marked angle between the cusp and visor. Teeth of Jurascyllium gen. nov. differ from those of Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. by having a broader uvula, the lack of a distinct and obtuse angle between visor and lateral cusplets, as well as the main cusp, more angular lateral edges, a more mesiodistally widened crown shoulder in lateral teeth. Teeth of Chiloscyllium Müller & Henle, 1837, can be distinguished from those of Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. by the wider main cusp aligned with the oral labial face, the shortened labial face, an elongated uvula and a lower root. Teeth of Palaeobrachaelurus Thies, 1982, can be differentiated from those of Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. by a mesio-distally narrow labial apron, the absence of angle between the cusp and the apron, a more elongated and enlarged uvula, and more erected lateral cusplets. Teeth of Heterophorcynus Underwood & Ward, 2004b, differ from those of Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. by mesio-distally narrower teeth, the more elongated uvula and labial visor, a strongly lingually projected main cusp, and the absence of angle between the cusp and the visor.

Material.—21 teeth from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of Rookery Pit, SE England.

Remarks.—The morphology of anterior teeth of Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. closely resembles that of teeth of extant hemiscyllids. However, its lateral and latero-posterior teeth differ significantly. Moreover, the number of margino-lingual foramina varies from one pair (anteriors) to three pairs (laterals), and up to more than five pairs in latero-posteriors. This unique combination of dental features distinguishes Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. from other orectolobiforms. Based on these distinctions, we agree with the interpretation of Underwood and Mitchell (1999) and consider these teeth as belonging to an orectolobiform. This conclusion is further supported by the presence of a mesio-distally broad labial visor projecting labially above the root, a character that we currently consider representing a typical orectolobiform tooth feature. Given this distinct combination of features, we assign this species to a new orectolobiform genus, Archaeoscyllium (Thies, 1982). Nevertheless, Archaeoscyllium gen. nov. cannot be assigned unambiguously to any family of Orectolobiformes.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of south-eastern England.

Archaeoscyllium muftium (Thies, 1982) comb. nov.

Fig. 8G, H.

1982 Protospinax? muftius; Thies 1982: 26, pl. 5 and 6.

1991 Protospinax muftius; Martill and Hudson 1991: 202, pl. 38.

2004 Protospinax? muftius; Underwood and Ward 2004a: 10.

Remarks.—We described a new monotypic genus Archaeoscyllium based on this species. The species is based on 21 teeth from the Callovian of south-east England. Thies (1982) tentatively assigned this species to Protospinax, based on supposed close morphological similarities. However, its dental morphologies differ significantly from those of species of Protospinax. Underwood and Mitchell (1999) provisionally included this species in the orectolobiform genus Pseudospinax Müller & Diedrich, 1991, from the Upper Cretaceous, but without any justification. Teeth of Pseudospinax pusillus Müller & Diedrich, 1991, present a flat labial surface with no concavity beneath the poorly developed main cusp. In contrast, the teeth of Archaeoscyllium muftium (Thies, 1982) have a well-developed upright main cusp with a rounded apex, which may result from usages and be related to diagenetic processes, forming an obtuse angle with the labial crown face in lateral view; present a pair of lateral cusplets flanking the main cusp long with a wide and rounded labial visor extending to the lateral cusplets. In contrast, the labial visor present in species of Pseudospinax teeth is mesio-distally shortened with a more rectangular outline in both labial and occlusal views.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of South-eastern England, UK.

Discussion

The dentition of Protospinax.—Unlike previous studies (Maisey 1976; Carvalho and Maisey 1996), our analysis of skeletal specimens indicates that adult Protospinax individuals possessed a relatively constant homodont crushing type dentition. The latero-posterior and commissural teeth differ from the anterior and antero-lateral teeth in cusp development, with the cusp becoming strongly reduced or even being absent in posterior teeth.

A gradual change in the root vascularization pattern from mesial to distal is also noticeable. In anterior and antero-lateral teeth of adult individuals the root is hemiaulacorhize, with no nutritive groove separating the root lobes. Latero-posterior teeth display a very narrow, still centrally closed nutritive groove. In more distal teeth including commissural teeth a holaulacorhize pattern is observed with a nutritive groove that is completely open. No evidence for dignathic heterodonty was observed (Figs. 3–7). Instead, the two different root vascularization types represent a gradual heterodonty pattern present in both the upper and lower jaws.

Juveniles share a similar dentition with adults but display a more pronounced main cusp in anterior teeth, which is less pronounced, but still developed in lateral and commissural teeth (Figs. 4, 5). The combination of this tooth crown pattern suggests a crushing-clutching type dentition sensu Cappetta (1986). These ontogenetic differences expressed in the dentition of Protospinax annectans most likely indicate a dietary shift from juveniles to adults.

Similarly to Protospinax annectans, other elasmobranch taxa display variations in tooth root vascularization. In the orectolobiform Parascyllium, for example, a change of the root vascularization type occurs along the upper and lower jaws (Herman et al. 1992: pls. 23, 25). The change in the root vascularization pattern, nevertheless, can also be related to ontogenetic changes. Teeth of Stegostoma tigrinum juveniles display the holaulacorhize vascularization pattern, while adults exhibit the hemiaulacorhize root vascularization one (Herman et al. 1992: pl. 30 and 31). Teeth of the extinct batomorph Onchopristis numida, for example also display both hemi- and holaulacorhize root vascularization patterns in the same species (Werner 1989; Villalobos-Segura et al. 2021). These intraindividual and intraspecific variations in root vascularization patterns, observed in Orectolobiformes, Sclerorhynchoidei, and Protospinacidae indicate that root vascularization is a very plastic feature. This renders its taxonomic and systematic significance, at the very least for these groups, insignificant contrary to the conclusion of Cappetta (1987, 2012). However, more detailed analyses are necessary to provide a more generalised observation for the remaining extant and extinct elasmobranch groups.

Chronostratigraphic range of Protospinax.—The extinct shark Protospinax is well represented by both isolated teeth and articulated skeletal remains in the Jurassic of Europe, but the exact temporal distribution is still unclear. Several findings indicate that the oldest records are from the Toarcian of northern Germany and Luxembourg, respectively (Thies 1989; Delsate and Lepage 1990; Delsate 2003), while the last occurrences were reported from the Valanginian (Lower Cretaceous; Guinot et al. 2014) and Cenomanian (Upper Cretaceous; Cappetta 2012), respectively.

However, the oldest record (Toarcian of Luxembourg), which is based on a single tooth, lacks any description. The tooth, shown in labial view (Delsate and Lepage 1990: fig. 3B), is widened and oval, and displays a non-centred lingually inclined cusp and sharp cutting edges. However, this single illustration does not allow a clear identification and attribution to Protospinax.

An additional record based on another single tooth from the Toarcian has been presented by Delsate and Weis (2010), which was assigned to Protospinax magnus. However, the description and figure do not allow any unambiguous identification but at least support its probable assignment to Protospinax as unidentified species. This record as well as the one from northern Germany, therefore, provide plausible evidence that Protospinax occurred in the Toarcian.

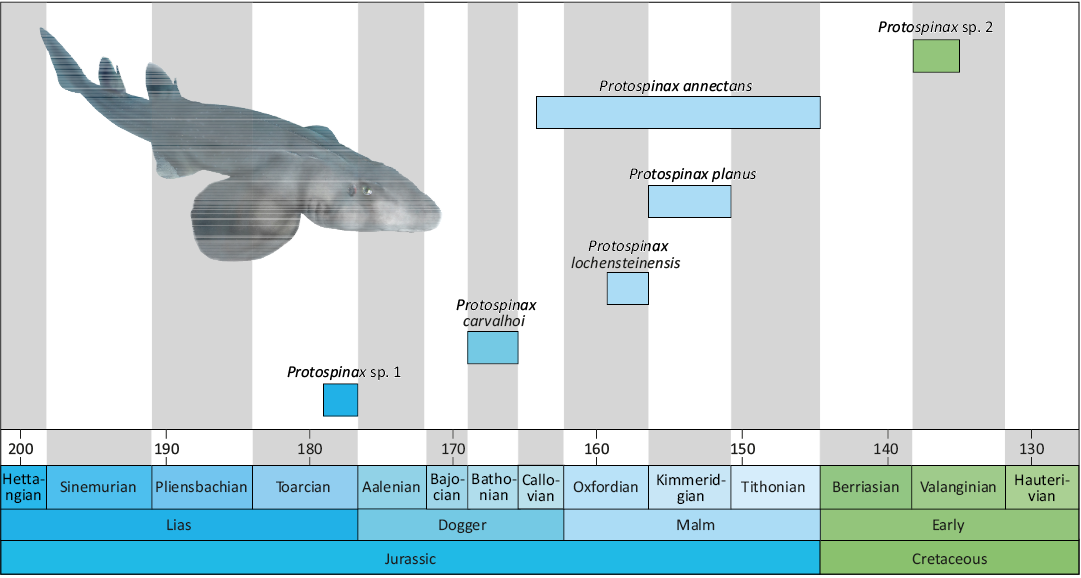

Early Cretaceous records of Protospinax come from the Valanginian of France (as Protospinax sp.), the Barremian and Aptian of England (as P. annectans) (Guinot et al. 2014; Batchelor and Ward 1990; Sweetman et al. 2014). The Valanginian occurrence can be undoubtedly assigned to the genus Protospinax but differs from the other species of Protospinax in the presence of a well-developed and sharp transversal crest. The specimens described by Batchelor and Ward (1990), conversely, do not belong to Protospinax, but rather to an indeterminate orectolobiform as the central cusp is accompanied by two low, rounded lateral cusplets, a feature never present in teeth of Protospinax. The two isolated teeth that were reported from the Barremian of England by Sweetman et al. (2014) seemingly appear to represent the stratigraphically youngest occurrence of the genus. However, the poor preservation of the teeth, only the tooth crown does allow a definite affiliation to Protospinax. Furthermore, the ornamentation on the labial crown face of the second tooth expresses a ridge reaching the labial visor in a perpendicular position to the transverse crest, raising the visor in labial view, are not typical features of Protospinax but rather resemble more those seen in orectolobiform teeth as observed in the genera Annea, Eometlaouia, Ornatoscyllium, and Delpitoscyllium (Arambourg 1952; Thies 1982; Noubhani and Cappetta 1997; Underwood and Ward 2004b). Additional and better-preserved material is needed to clarify the potential presence of Protospinax during the Barremian. Consequently, the validated stratigraphic range of Protospinax is Toarcian (Lower Jurassic) to Valanginian (Lower Cretaceous) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Chronostratigraphic range of Protospinax species based on the fossil record re-evaluation in this study. Protospinax sp. 1 represents the specimen described by Thies (1989), Protospinax sp. 2 corresponds to the teeth described by Guinot et al. (2014). Protospinax illustration by Manuel A. Staggl (see Jambura et al. 2023).

Conclusions

The detailed study of the dentitions of holomorphic specimens, both adult and juvenile, allowed us to establish a general pattern of dental heterodonties of Protospinax annectans. However, identification and characterisation of more specific heterodonty patterns such as dignathic, ontogenetic or sexual dimorphic variations remain inconclusive due to the limited material available and state of preservation. Nevertheless, the present study provides essential information and new perspectives on the significance of the root vascularization pattern in this genus, which can vary from hemi- to holaulacorhize within the dentition (in adults) or during ontogenetic development, rendering this character insignificant for taxonomic purposes, at least in Protospinax and several orectolobiforms. Further studies are needed to determinate whether the vascularization pattern of the root bears any taxonomic signal in elasmobranchs at all.

The present study thus highlights the importance of detailed work on the complete dentition of both extant and extinct elasmobranchs, to provide a more robust classification for fossil taxa based on isolated teeth and to avoid parataxonomy (Guinot et al. 2018). Based on our results, the known number of species assigned to the extinct shark, Protospinax, is reduced, while two new Jurassic orectolobiforms are identified, significantly changing the diversity patterns for both groups in the Jurassic. The present re-evaluation of holomorphic specimens of Protospinax annectans demonstrates that future taxonomical revisions of elasmobranch dentitions based on additional holomorphic material are essential to improve our understanding of diversity patterns through time, as they have direct influences on any interpretation of spatial and temporal distributions as well as origination and extinction patterns in deep time, as most of their fossil record consists of isolated teeth.

Authors’ contributions

JK and EVS conceived and designed the project. AB, PLJ, and MAS photographed the holomorphic specimens. AB photographed isolated teeth with Digital Microscope and SK with Scanning Electron Microscope and prepared the first draft of the manuscript and all figures. AB and PLJ performed the dental analyses. MAS performed Protospinax annectans reconstruction (see Jambura et al. 2023). All authors contributed equally to the final manuscript version.

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare to have any conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to Martina Kölbl-Ebert, Andreas Hecker, and Christina Ifrim (all JME-SOS), Oliver W.M. Rauhut (SNSB-BSPG), and Emma Bernard (NHMUK) for access to holomorphic specimens of Protospinax annectans in their collections. Erin Maxwell (SMNS) is acknowledged for the possibility to study the material from the locality of Mahlstetten (Germany). We would like to thank Detlev Thies (Leibniz University Hannover, Germany) and Christopher Duffin (NHMUK) for their helpful comments on the manuscript. Last but not least, we thank Elmar Unger (Aulendorf, Germany) for his generosity for making his great collection and fossils from the Mahlstetten locality available to science. This research was funded in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (P 35357) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) (No. 5448423) to JK and SK, respectively.

Editor: Krzysztof Hryniewicz

References

Arambourg, C. 1952. Les vertébrés fossiles des gisements de phosphates. Notes et Mémoires du Service géologique du Maroc 92: 1–372.

Applegate, S.P. 1972. A revision of the higher taxa of orectolobids. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India 14: 743–751.

Batchelor, H. and Ward, D.J. 1990. Fish remains from a temporary exposure of Hythe Beds (Aptian–Lower Cretaceous) near Godstone, Surrey. Mesozoic Research 2: 181–203.

Begat, A., Kriwet, J., Gelfo, J.N., Cavalli, S.G., Schultz, J.A., and Martin, T. 2023. The first southern hemisphere occurrence of the extinct Cretaceous sclerorhynchoid sawfish Ptychotrygon (Chondrichthyes, Batoidea), with a review of Ptychotrygon taxonomy. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 42: e2162411. Crossref

Bonaparte, C.L. 1838. Synopsis vertebratorum systematis. Nuovi Annali delle Scienze Naturali 2: 105–133.

Cappetta, H. 1970. Les Sélaciens du Miocène de la région de Montpellier. Palaeovertebrata 1970: 1–139. Crossref

Cappetta, H. 1986. Types dentaires adaptatifs chez les sélaciens actuels et post-paléozoïques. Paleovertebrata 16: 57–76.

Cappetta, H. 1987. Chondrichthyes II: Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii. 193 pp. Verlag, New York.

Cappetta, H. 2012. Chondrichthyes: Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii: Teeth. In: H.-P. Schultze (ed.), Handbook of Paleoichthyology, Volume 3E, 1–512, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, Munich.

Cappetta, H. and Case, G.R. 2016. A selachian fauna from the middle Eocene (Lutetian, Lisbon Formation) of Andalusia, Covington County, Alabama, USA. Palaeontographica A 307: 43–103. Crossref

Carvalho, M.R., de and Maisey, J.G. 1996. Phylogenetic relationships of the Late Jurassic Protospinax Woodward 1919 (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii). In: G. Arratia and G. Viohl (eds.), Mesozoic Fishes, 9–46. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München.

Case, G.R. and Cappetta, H. 1997. A new selachian fauna from the Late Maastrichtian of Texas (Upper Cretaceous/Navarro Group; Kemp Formation). Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen Reihe A, Geologie und Paläontologie 34: 131–189.

Casier. E. 1947. Constitution et évolution de la racine dentaine des Euselachii. Bulletin du Musée royal d’Histoire naturelle de Belgique 23: 1–43.

Castro, J.I. 1993. The shark nursery of Bulls Bay, South Carolina, with a review of the shark nurseries of the southeastern coast of the United States. Environmental Biology of Fishes 38: 37–48. Crossref

Cicimurri, D.J. and Weems, R.E. 2021. First record of Ptychotrygon rugosum (Case, Schwimmer, Borodin, and Leggett, 2001) (Batomorphii, Sclerorhynchiformes, Ptychotrygonidae) in the United States Atlantic Coastal Plain. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41: e1933996. Crossref

Compagno, L.J.V. 1973. Interrelationships of living elasmobranchs. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 53: 15–61.

Dearden, R.P., Johanson, Z., O’Neill, H.L., Bernard, E.L., Clark, B., Underwood, C., and Rücklin, M. 2025. Three dimensional fossils of a Cretaceous collared carpet shark (Parascyllidae, Orectolobiformes) shed light on skeletal evolution in galeomorphs. Royal Society Open Science 12: 1–15. Crossref

Delsate, D. 2003. Une nouvelle faune de poissons et requins toarciens du Sud du Luxembourg (Dudelange) et de l’Allemagne (Schömberg). Bulletin de l’Académie Lorraine des Sciences 42: 1–28.

Delsate, D. and Felten, R. 2015. Chondrichthyens et actinoptérygiens du Bajocien inférieur du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg et des régions frontalières. Ferrantia 71: 9–38.

Delsate, D. and Lepage, J.C. 1990. Découverte d’une faune originale d’élasmobranches dans les phosphates du Toarcien Lorrain (couches à Coeloceras crassum). Bulletin de l’Académie et de la Société lorraines des Sciences 29: 153–161.

Delsate, D. and Weis, R. 2010. La Couche à Crassum (Toarcien moyen) au Luxembourg: Stratigraphie et faunes de la coupe de Dudelange-Zoufftgen. Ferrantia 62: 35–62.

Duncan, K.M. and Holland, K.N. 2006. Habitat use, growth rates and dispersal patterns of juvenile scalloped hammerhead sharks Sphyrna lewini in a nursery habitat. Marine Ecology Progress Series 312: 211–221. Crossref

Duffin, C.J. 1993. New records of Late Jurassic sharks teeth from Southern Germany. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 193: 1–13.

Guinot, G., Adnet, S., Shimada, K., Underwood, C.J., Siversson, M., Ward, D.J., Kriwet, J., and Cappetta, H. 2018. On the need of providing tooth morphology in descriptions of extant elasmobranch species. Zootaxa 4461: 118–126. Crossref

Guinot, G., Cappetta, H., and Adnet, S. 2014. A rare elasmobranch assemblage from the Valanginian (Lower Cretaceous) of southern France. Cretaceous Research 48: 54–84. Crossref

Herman, J., Hovestadt-Euler, M., and Hovestadt, D.C. 1992. Contributions to the study of the comparative morphology of teeth and other relevant ichthyodorulites in living supraspecific taxa of chondrichthyan fishes. Part A: Selachii. No. 4: Order: Orectolobiformes—Families: Brachaeluridae, Ginglymostomatidae, Hemiscylliidae, Orectolobidae, Parascylhidae, Rhiniodontidae, Stegostomatidae. Order: Pristiophoriformes—Family: Pristiophoridae. Order: Squatiniformes—Family: Squatinidae. Bulletin de l’Institut royale des Sciences naturelles de Belgique 62: 193–254.

Huxley, T.H. 1880. On the application of the laws of evolution to the arrangement of the Vertebrata, and more particularly of the Mammalia. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1880: 649–661.

ICZN [International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature] 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Fourth Edition. xxix + 306 pp. International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, London.

Jambura, P.L., Villalobos-Segura, E., Türtscher, J., Begat A., Staggl, M.A., Stumpf, S., Kindlimann, R., Klug, S., Lacombat, F., Pohl, B., Maisey, J.G., Naylor, G., and Kriwet, J. 2023. Systematics and phylogenetic interrelationships of the enigmatic Late Jurassic shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 with comments on the shark-ray sister group relationship. Diversity 15 (3): 311. Crossref

Klug, S. 2009. A new palaeospinacid shark (Chondrichthyes, Neoselachii) from the Upper Jurassic of southern Germany. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29: 326–335. Crossref

Klug, S. and Kriwet, J. 2013. An offshore fish assemblage (Elasmobranchii, Actinopterygii) from the Late Jurassic of NE Spain. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 87: 235–257. Crossref

Kriwet, J. 2003. Neoselachian remains (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) from the Middle Jurassic of SW Germany and NW Poland. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48: 583–594.

Kriwet, J. and Klug, S. 2004. Late Jurassic selachians (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) from southern Germany: Re-evaluation on taxonomy and diversity. Zitteliana A 44: 67–95. Crossref

Kriwet, J., Nunn, E. V., and Klug, S. 2009. Neoselachians (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) from the Lower and lower Upper Cretaceous of north-eastern Spain. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 155: 316–347. Crossref

Landini, W., Collareta, A., Pesci, F., Di Celma, C., Urbina, M., and Bianucci, G. 2017. A secondary nursery area for the copper shark Carcharhinus brachyurus from the late Miocene of Peru. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 78: 164–174. Crossref

Latham, J. 1794. An essay on the various species of sawfish. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 2: 273–282. Crossref

Lesson, R.P. 1831. Poissons. In: L.I. Duperrey (ed.), Voyage autour du Monde, exécuté par Ordre du Roi, sur la Corvette de Sa Majesté, La Coquille, pendant les années 1822, 1823, 1824 et 1825, 66–238. Arthus Bertrand, Paris.

Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. 824 pp. Laurentius Salvius, Stockholm. Crossref

Maisey, J.G. 1976. The Jurassic Selachian Fish Protospinax Woodward. Palaeontology 19: 733–747.

Maisey, J.G. 2012. What is an ‘elasmobranch’? The impact of palaeontology in understanding elasmobranch phylogeny and evolution. Journal of Fish Biology 80: 918–951. Crossref

Manzanares, E., Pla, C., Martínez-Pérez, C., Ferrón H., and Botella, H. 2017. Lonchidion derenzii, sp. nov., a new lonchidiid shark (Chondrichthyes, Hybodontiforms) from the Upper Triassic of Spain, with remarks on lonchidiid enameloid. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37: e1253585. Crossref

Martill, D.M. and Hudson, J.D. 1991. Fossils of the Oxford Clay. Palaeontological Association Field Guide to Fossils 4: 1–287.

Müller, A. and Diedrich, C. 1991. Selachier (Pisces, Chondrichthyes) aus dem Cenomanium von Ascheloh am Teutoburger Wald (Nordrhein-Westfalen, NW-Deutschland). Geologie und Paläontologie in Westfalen 20: 1–105.

Müller, J. and Henle, F.G.J. 1837. Gattungen der Haifische und Rochen nach einer von ihm mit Hrn; Henle unternommenen gemeinschaftlichen Arbeit über die Naturgeschichte der Knorpelfische. Berichte der Königlichen Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1837 (2): 111–118.

Müller J. and Henle F.G.J. 1838. Ueber die Gattungen der Plagiostomen. Archiv für Naturgeschichte 4: 83–85.

Nelson, J.N. 1984. Fishes of the World. Second Edition. 523 pp. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Noubhani, A. and Cappetta, H. 1997. Les Orectolobiformes, Carcharhiniformes et Myliobatiformes des bassinsa phosphate du Maroc (Maastrichtien–Lutétien basal). Palaeo Ichthyologica 8: 1–327.

Ogilby, J.D. 1906. On new genera and species of fishes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland 21: 1–26. Crossref

Pimiento, C., Ehret, D.J., MacFadden, B.J., and Hubbell, G. 2010. Ancient nursery area for the extinct giant shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama. PLoS ONE 5 (5): 0010552. Crossref

Rees, J. and Underwood, C.J. 2002. The status of the shark genus Lissodus Brough, 1935 and the position of the nominal Lissodus species within the Hybodontoidea (Selachii). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22: 471–479. Crossref

Schaeffer, B. 1967. Comments on elasmobranch evolution. In: P.W. Gilbert, R.F. Matthewson, and D.P. Rall (eds.), Sharks, Skates and Rays, 3–35. John Hopkins Press, Baltimore.

Schweigert, G. 2007. Ammonite biostratigraphy as a tool for dating Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones from South Germany: first results and open questions. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. Abhandlungen 245: 117–125. Crossref

Siverson, M. 1995. Revision of Cretorectolobus (Neoselachii) and description of Cederstroemia n. gen., a Cretaceous carpet shark (Orectolobiformes) with a cutting dentition. Journal of Paleontology 69: 974–979. Crossref

Sweetman, S.C., Goedert, J., and Martill, D.M. 2014. A preliminary account of the fishes of the Lower Cretaceous Wessex Formation (Wealden Group, Barremian) of the Isle of Wight, southern England. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 113: 872–896. Crossref

Thies, D. 1982. Jurazeitliche Neoselachier aus Deutschland und S-England. Courier Forschunginstitut Senckenberg 58: 1–116.

Thies, D. 1989. Some problematical sharks teeth (Chondrichthyes, Neoselachii) from the Early and Middle Jurassic of Germany. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 63: 103–117. Crossref

Thies, D. and Leidner, A. 2011. Sharks and guitarfishes (Elasmobranchii) from the Late Jurassic of Europe. Palaeodiversity 4: 63–184.

Thiollière, V. 1852. Troisième notice sur les gisements à poissons fossiles situés dans le Jura du département de l’Ain. Annales des Sciences Physiques et Naturelles, d’Agriculture et d’Industrie 4: 353–446.

Underwood, C.J. 2002. Sharks, rays and a chimaeroid from the Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) of Ringstead, Southern England. Palaeontology 45: 297–325. Crossref

Underwood, C.J. 2004. Environmental controls on the distribution of neoselachian sharks and rays within the British Bathonian (Middle Jurassic). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoclimatology 203: 107–126. Crossref

Underwood, C.J. 2006. Diversification of the Neoselachii (Chondrichthyes) during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Paleobiology 32: 215–235. Crossref

Underwood, C.J. and Mitchell, S. 1999. Albian and Cenomanian (Cretaceous) selachians faunas from North East England. Special Papers in Palaeontology 60: 9–59.

Underwood, C.J. and Ward, D.J. 2004a. Environmental distribution of Bathonian (Middle Jurassic) neoselachians in southern England. In: G. Arratia and A. Tintori (eds.), Mesozoic Fishes 3—Systematics, Palaeoenvironments and Biodiversity, 111–122. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München.

Underwood, C.J. and Ward, D.J. 2004b. Neoselachian sharks and rays from the British Bathonian (Middle Jurassic). Palaeontology 47: 447–501. Crossref

Villafaña, J.A., Hernandez, S., Alvarado, A., Shimada, K., Pimiento, C., Rivadeneira, M.M., and Kriwet, J. 2020. First evidence of a palaeo-nursery area of the great white shark. Scientific Reports 10: 8502. Crossref

Villalobos-Segura, E., Kriwet, J., Vullo, R., Stumpf, S., Ward, D.J., and Underwood, C.J. 2021. The skeletal remains of the euryhaline sclerorhynchoid †Onchopristis (Elasmobranchii) from the ‘Mid’-Cretaceous and their palaeontological implications. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 193: 746–771. Crossref

Villalobos-Segura, E., Underwood, C.J., and Ward, D.J. 2019. The first skeletal record of the enigmatic Cretaceous sawfish genus Ptychotrygon (Chondrichthyes, Batoidea) from the Turonian of Morocco. Papers in Palaeontology 7: 353–376. Crossref

Werner, C. 1989. Die Elasmobranchier-Fauna des Gebel Dist Member der Bahariya Formation (Obercenoman) der Oase Bahariya, Ägypten. Palaeo Ichthyologica 5: 1–112.

Woodward, A.S. 1918. On two new elasmobranch fishes (Crossorhinus jurassicus sp. nov. and Protospinax annectans gen. et sp. nov.) from the Upper Jurassic lithographic stone of Bavaria. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 13: 231–235. Crossref

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 731–748, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01260.2025