First occurrences of neural canal ridges in Crocodylia

WILLIAM JUDE HART, JESSIE ATTERHOLT, and MATHEW J. WEDEL

Crocodylia is a crown group inclusive of the last common ancestor of extant crocodylians, followed by successive extinct and extant taxa forming Alligatoroidea, Crocodyloidea, and Gavialoidea. Rigorous work on fossil and extant crocodylian postcrania is vital for understanding the evolution of their functional morphology. Here, we document neural canal ridges (NCRs) in the genera Thecachampsa and Deinosuchus. The morphology of the NCRs in these taxa is consistent with bony spinal cord supports that anchor the denticulate ligaments in extant taxa. To date, we have only found NCRs in the caudal vertebrae of Thecachampsa and Deinosuchus, consistent with the serial distribution of NCRs in non-avian dinosaurs. However, NCRs are present in more regions of the vertebral column in non-amniotes, and absent in Anura, Aves, and Mammalia. Many vertebrate clades await systematic surveys for NCRs, in both fossil and extant representatives. Additional methods, such as osteohistology and embryology, may shed further light on the functional morphology and biomechanical underpinnings of neural canal ridge development and evolution. Our findings expand known axial postcranial morphology in Crocodylia and broaden the known distribution of NCRs in vertebrates.

Introduction

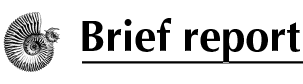

While studying vertebral development of extant salamanders, Wake and Lawson (1973) discovered ossified “nerve cord supports” in the neural canals; these are bony protrusions projecting medially from the lateral wall of the neural canal that anchor the denticulate ligaments that support the spinal cord. Skutschas (2009) subsequently reported the presence of these structures in fossil salamanders from the Upper Cretaceous. Skutschas and Baleeva (2012) broadly surveyed vertebrates for bony spinal cord supports, recovering them in extant bony fish, lungfish, additional extant species of salamander, and possibly within a squamate. Averianov and Lopatin (2020) and Atterholt et al. (2024) identified similar bony structures in various non-avian dinosaurs. The latter authors referred to these structures as “neural canal ridges” (NCRs), evaluated multiple hypotheses for their function, and favored the hypothesis that they are osteological correlates of the denticulate ligaments. Santos et al. (2025) and Zverkov et al. (2025), respectively, identified “spinal cord supports” for the first time in caecilians and plesiosaurs. However, there are still clades that have not yet been assessed for the presence of these structures (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Cladograms representing neural canal ridges (NCRs) across Vertebrata. A. Overview of NCRs occurring in select clades. B. Overview of Crocodylia with NCR occurrence per this paper’s results.

Herein we document the first occurrence of neural canal ridges (NCRs) in fossil crocodylians (Fig. 1B), specifically the Miocene tomistomine gavialoid Thecachampsa and the Upper Cretaceous Deinosuchus, which may be an alligatoroid (Cossette and Brochu 2020) or a stem crocodylian (Walter et al. 2025). Osteological correlates for specific soft tissue structures in extant crocodylians have been of interest for inferring the presence of similar structures in extinct taxa, yet most osteological correlates currently known are restricted to the skull and appendicular skeleton (e.g., Fujiwara et al. 2010; Schachner et al. 2021; Grand Pré et al. 2023). Less work has been done on osteological correlates of the crocodyliform axial postcranium (but see Frey et al. 1989; Wilhite 2023).

Institutional abbreviations.—AMNH FR, American Museum of Natural History, Fossil Reptiles, New York, USA; WSC, Western Science Center, Hemet, USA.

Other abbreviations.—NCR, neural canal ridge.

Material and methods

As part of a descriptive project on a specimen of Thecachampsa sp. (AMNH FR 34089; Hart et al. 2024), one of us (WJH) noted that NCRs were observed inside the neural canal. This inspired a survey of fossil crocodylian vertebrae in other collections, which is currently ongoing and led to our subsequent discovery of NCRs in a specimen of Deinosuchus sp. (WSC 285.8). We are currently undertaking a broader survey of NCRs in extant and fossil crocodylians, the results of which will be presented elsewhere. Measurements of the Thecachampsa sp. and Deinosuchus sp. vertebrae are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Measurements (in mm) of specimens used in this study. See Institutional abbreviations regarding specimen numbers. Abbreviations: CH, centrum height; CL, centrum length; N/A, not avaliable; NCW, neural canal width; TH, total height; TL, total length; WR, width ratio.

|

Specimen number |

NCW anterior end |

NCW posterior end |

CH anterior end |

CH posterior end |

CL |

TH |

TL |

TL : WR |

|

AMNH FR 34089 |

16.1 |

15.5 |

44.3 |

44.3 |

73 |

82.6 |

96 |

1.16 |

|

WSC 285.8 |

14 |

7 |

60 |

~40 |

115 |

>90 |

115 |

N/A |

AMNH FR 34089 was recovered from a rockfall deposit from the Conoy Member of the Uppermost Choptank Formation, dated to ~11.6–11.0 Ma (Tortonian, Late Miocene; Kidwell et al. 2015) during a 1998 Geological Society of America Penrose meeting field trip in the Calvert Cliffs Fossil Region of Maryland (Hart et al. 2024; Fig. 2).

Systematic palaeontology

Crocodylia Gmelin, 1789

Gavialidae Adams, Baikie, & Barron, 1854

Tomistominae Kälin, 1955

Genus Thecachampsa Cope, 1867

Type species: Thecachampsa sericodon Cope, 1867, Middle Miocene of the Upper Plum Point Member, Calvert Formation near the residence of James T. Thomas, near the Patuxent River, Charles County, Maryland, USA.

Thecachampsa sp.

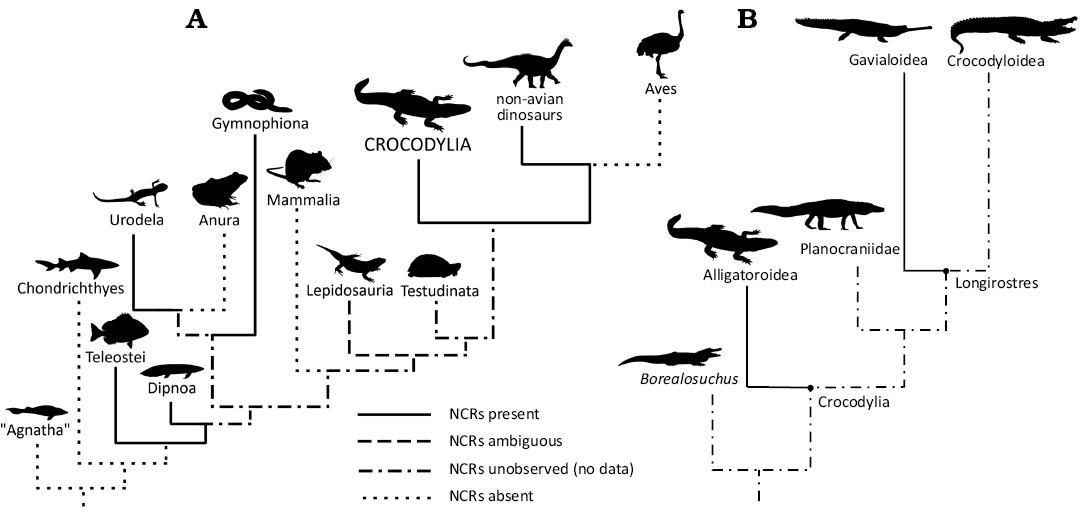

Fig. 2.

Material.—AMNH FR 34089, an isolated caudal vertebra of a large crocodylian from the Conoy Member of the Uppermost Choptank Formation (~11.6–11.0 Ma, Tortonian, Miocene; Kidwell et al. 2015), Calvert Cliffs Fossil Region, Maryland, USA.

Description.—The vertebra lacks pre- and post-zygapophyses, the right transverse process, the dorsal half of the neural spine, and the chevron. Some minor breakage is present around the posterior condyle, with some cracking along the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the centrum. The articular surfaces for the haemal arch have both minor breakage and erosion. The left transverse process has been restored with putty clay. Overall, the morphology of the vertebra best resembles one of the anteriormost caudals of Thecachampsa, a large-bodied tomistomine gavialoid known to be present along the Atlantic seaboard during the late Oligocene–Late Miocene (cf., caudal 2–4; see Piras et al. 2007; Klein 2016; Hart et al. 2024).

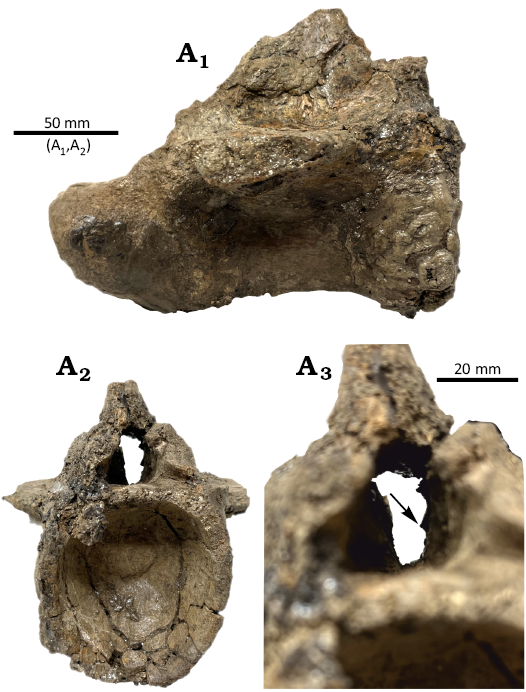

The neural canal in AMNH FR 34089 is mediolaterally wider ventrally than dorsally but lacks the pronounced bilobed morphology present in some other crocodylian vertebrae (see Zippel et al. 2003). Ventrolaterally within the neural canal, paired longitudinal ridges show where the neurocentral joints were located, but the joints are fully fused with no open suture line, indicative of the individual being late in ontogeny at the time of death (Brochu 1996). Paired, shallow grooves run anterioposteriorly along the floor of the neural canal and have small foramina; these are likely neurovascular channels (Wedel et al. 2021). Projecting medially from the lateral walls of the neural canal are small, paired, bony ridges with sharp medial edges (Fig. 2A2–A4). These NCRs are most like, but even more pronounced than, the NCRs in a juvenile Alamosaurus (Atterholt et al. 2024: fig. 6D). The NCRs in AMNH FR 34089 are slightly below the dorsoventral midpoint of the neural canal, near its anterioposterior midpoint, roughly even with shallow fossae on the lateral aspects of the neural spine.

Fig. 2. Caudal vertebra of gavialid crocodylian Thecachampsa sp. from Calvert Cliffs Fossil Region, Maryland, USA, Conoy Member of the Uppermost Choptank Formation, Tortonian, Miocene. AMNH FR 34089 in right lateral (A1) and posterior (A2) views with the node denoting the location of the upper recess for the venous sinus. View of the interior neural canal on an oblique angle in right (A3) and left (A4) lateral views. Arrows point to the neural canal ridge.

Crocodylia Gmelin, 1789

Alligatoroidea Gray, 1844

Genus Deinosuchus Holland, 1909

Type species: Deinosuchus hatcheri Holland, 1909, middle Campanian, Judith River Formation, three miles west of Nolan and Archer’s ranch along the Willow Creek, Fergus County, Montana, USA.

Deinosuchus sp.

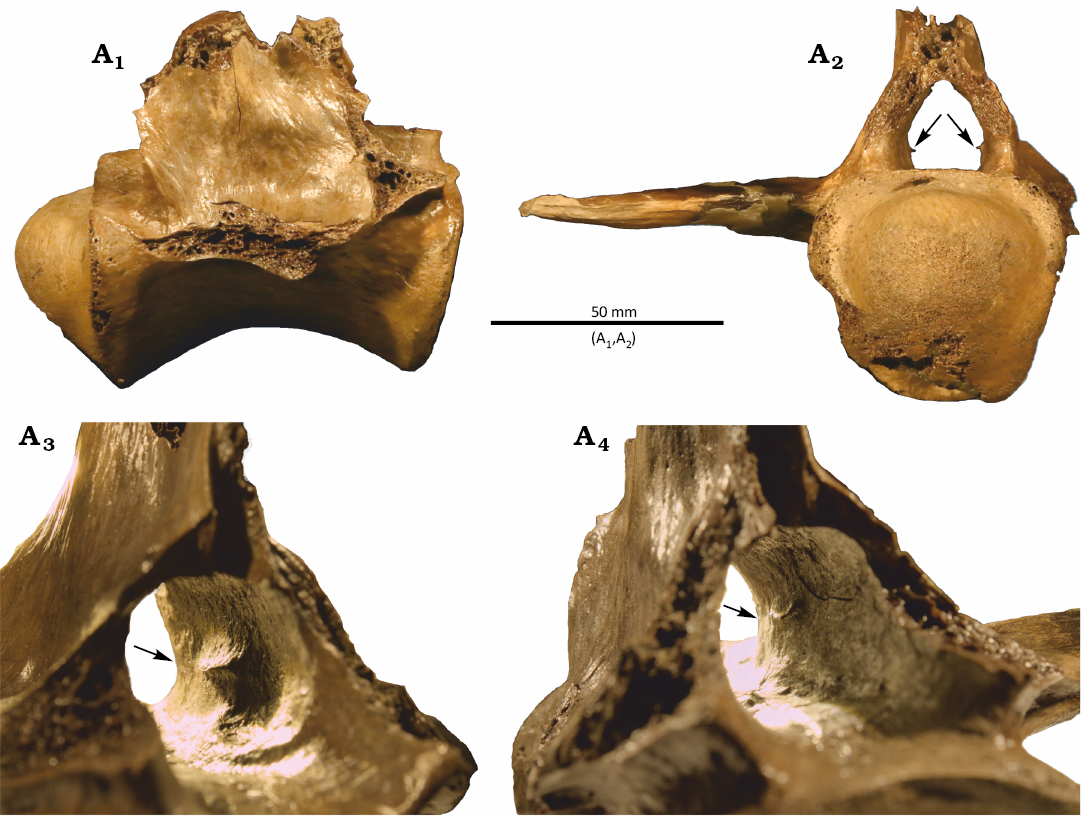

Fig. 3.

Material.—WSC 285.8, proximal caudal vertebra from the Allison Member of the Menefee Formation (~78.2–78.5 Ma, Campanian, Late Cretaceous; Mohler et al. 2021), Juan Lake Beds, whilst the country is San Juan County, New Mexico, USA.

Description.—WSC 285.8 is missing the following: both transverse processes, pre- and post-zygapophyses, the dorsal half of the neural spine, anterior and posterior ends of the neural canal roof, and chevron. The articular surfaces for the haemal arch, the anterior cotyle, and posterior condyle are broken and worn. Despite abrasion, most of the original bone surface is preserved.

The neural canal is crushed mediolaterally, which makes inferring any anatomical detail difficult (Fig. 3A2); however, its interior has been prepared free of matrix. The presence of a dorsal recess for the venous sinus is ambiguous. A short bony ridge projects medially about halfway up the left wall of the neural canal, at roughly the anteroposterior midpoint of the canal. This ridge is anteroposteriorly elongated and tallest at its midpoint, most like the NCRs in a caudal vertebra of the sauropod Astrophocaudia illustrated by Atterholt et al. (2024: fig. 6C). In WSC 285.8, no corresponding ridge is present on the right side of the neural canal, but this is probably a result of poor preservation rather than a genuine anatomical absence.

Fig. 3. Caudal vertebra of alligatoroid crocodylian Deinosuchus sp. from Allison Member of the Menefee Formation, middle Campanian, Juan Lake Beds, whilst country is San Juan County, New Mexico, USA. WSC 285.8 in right lateral (A1) and anterior (A2) views. Close-up on the anterior cotyle in anterior view (A3). Arrow points to the neural canal ridge.

Discussion

NCRs have previously been identified in a phylogenetically broad subset of vertebrate clades (Fig. 1A), including teleosts, dipnoans, salamanders, caecilians, plesiosaurs, and non-avian dinosaurs. The results presented here add crocodylians to this list. The phylogenetic positions of Thecachampsa as a gavialoid and Deinosuchus as either an alligatoroid or a stem-crocodylian (Cossette and Brochu 2020; Walter et al. 2025) suggest that NCRs may be more broadly distributed in Crocodylia.

Previous work on NCRs in extant taxa has established that they anchor the denticulate ligaments that support the spinal cord (Wake and Lawson 1973; Skutchas 2009; Skutchas and Baleeva 2012). Unlike other taxa with NCRs, the crocodylian neural canal houses both the spinal cord and a large dorsal venous sinus, often giving the neural canal a bilobed morphology. The “waist” of the bilobed neural canal, when present, anchors connective tissues associated with the dorsal venous sinus and the spinal cord (Parker et al. 2024). NCRs documented here in Thecachampsa and Deinosuchus are restricted to the central third of the anteroposterior length of the canal and do not alter the overall geometry of the canal by conferring a bilobed shape (see discussion in Atterholt et al. 2024). They also do not occur in vertebrae with bilobed neural canals; thus, the NCRs are visible as distinct structures. Nonetheless, more work is necessary to establish unequivocally whether crocodylian NCRs are indeed bony spinal cord supports, and whether they can co-occur with bilobed neural canals present in some taxa (e.g., Alligator; Klein 2016; Atterholt et al. 2024). The potential presence of both denticulate ligaments and soft-tissue septa associated with the dorsal venous sinus also requires elucidation by careful dissection, soft-tissue and osteohistology, or all of the above.

To date, we have only found NCRs in caudal vertebrae of crocodylians, which is consistent with their expression in non-avian dinosaurs (Atterholt et al. 2024). The apparent restriction of NCRs to the caudal vertebrae in archosaurs is puzzling, given that NCRs can be present in any region of the vertebral column in non-amniotes (Skutschas and Baleeva 2012; Santos et al. 2025). A necessary caveat is that the presence of NCRs in archosaurs has only recently been established, and no systematic surveys have been done to explore their distribution either phylogenetically across Archosauria or serially within well-preserved complete skeletons. Nevertheless, NCRs are prevalent in clades with laterally undulating locomotion (e.g., Teleosti; Skutchas and Baleev 2012), tail-driven femur retraction (e.g., Dinosauria; Atterholt et al. 2024), or both (e.g., Urodela; Wake and Lawson 1972), and absent in clades that have more rigid torsos, an absence of tail-driven femur retraction, or both, such as Anura, Aves, and Mammalia (Fig. 1A). This apparent distribution is consistent with the hypothesis that NCRs anchor the spinal cord against lateral undulatory motion. The hypothesis that NCRs serve a biomechanical function by anchoring denticulate ligaments is tantalizing, but much work remains to be done.

Concluding remarks

Further surveys of NCRs in Crocodyliformes and other vertebrate clades, both extinct and extant, are crucial. In particular, complete vertebral series of extant and well-preserved fossil crocodylians will be critical for gauging serial and ontogenetic variation in NCR expression (Araújo and Fernandez 2023) and countering possible losses caused by poor preservation, incomplete ossification, or historical preparation techniques (Green 2001). The vertebrate neural canal is an area of great paleobiological relevance yet remains understudied. Extant crocodylians could provide model systems for investigating the embryological and post-hatching development of NCRs, as well as their functional morphology, to better clarify the role of NCRs in vertebrate anatomy and evolution. To this end, we are currently working to extend our sampling to extant crocodylians, and we will present those results in the future.

Acknowledgements.—We thank Carl Mehling (AMNH), Andrew J. McDonald and Alton Dooley (both WSC) for access to specimens in their care. We also thank J. Bret Bennington (Hofstra University, Hempstead, USA) for recovering, curating, and preserving AMNH FR 34089 before donation, as well as Ezekiel O’Callaghan (Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, USA) for reviewing the abstract draft. Lastly, we thank Eric Wilberg and Harrison Allen (both Stony Brook University, New York, USA), and Matthew Bonnan (Stockton University, Galloway Township, USA) for fruitful conversations at the 2025 Northeastern Regional Vertebrate Evolution Symposium, as well as Daniela Schwarz (Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany) and another anonymous person for their reviews.

Editor: Daniel Barta

References

Araújo, R. and Fernandez, V. 2023. Three-dimensional developmental anatomical atlas of the Crocodylus niloticus skeleton. In: H.N. Woodward and J.O. Farlow (eds.), Ruling Reptiles: Crocodylian Biology and Archosaur Paleobiology, 10–50. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Crossref

Atterholt, J., Wedel, M.J., Tykoski, R., Fiorillo, A.R., Holwerda, F., Nalley, T.K., Lepore, T., and Yasmer, J. 2024. Neural canal ridges: A novel osteological correlate of postcranial neuroanatomy in dinosaurs. The Anatomical Record 308: 1349–1368. Crossref

Averianov, A.O. and Lopatin, A.V. 2020. An unusual new sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 18: 1009–1032. Crossref

Brochu, C.A. 1996. Closure of neurocentral sutures during crocodilian ontogeny: implications for maturity assessment in fossil archosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16: 49–62. Crossref

Cossette, A.P. and Brochu, C.A. 2020. A systematic review of the giant alligatoroid Deinosuchus from the Campanian of North America and its implications for the relationships at the root of Crocodylia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40: e1767638. Crossref

Frey, E., Riess, J., and Tarsitano, S.F. 1989. The axial tail musculature of Recent crocodiles and its phyletic implications. American Zoology 29: 857–862. Crossref

Fujiwara, S.I., Taru, H. and Suzuki, D. 2010. Shape of articular surface of crocodilian (Archosauria) elbow joints and its relevance to sauropsids. Journal of Morphology 271: 883–896. Crossref

Grand Pré, C.A., Thielicke, W., Diaz Jr., R.E., Hedrick, B.P., Elsey, R.M., and Schachner, E.R. 2023. Validating osteological correlates for the hepatic piston in the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). PeerJ 11: e16542. Crossref

Green, O.R. 2001. Mechanical methods of preparing fossil specimens. In: A Manual of Practical Laboratory and Field Techniques in Palaeobiology, 110–119. Springer, Dordrecht. Crossref

Hart, W.J., Hill, R.V., and Bennington, J.B. 2024. A caudal vertebra from Thecachampsa sp. (Crocodylia: Tomistominae) with comments on systematics. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 84th Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts, 243. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Minneapolis.

Klein, G.F. 2016. Skeletal Anatomy of Alligator and Comparison with Thecachampsa. 70 pp. Calvert Marine Museum, Solomons.

Kidwell, S.M., Powars, D.S., Edwards, L.E., and Vogt, P.R. 2015. Miocene stratigraphy and paleoenvironments of the Calvert Cliffs, Maryland. In: D.K. Brzesinski, J.P. Halka, and R.A. Orrt Jr. (eds.), Tripping from the Fall Line: Field Excursions for the GSA Annual Meeting, Baltimore, 2015. Geological Society of America Field Guide 40: 231–279. Crossref

Mohler, B.F., McDonald, A.T., and Wolfe, D.G. 2021. First remains of the enormous alligatoroid Deinosuchus from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation, New Mexico. PeerJ 9: e11302. Crossref

Parker, S., Cramberg, M., Scott, A., Sopko, S., Swords, A., Taylor, E., and Young, B.A. 2024. On the spinal venous sinus of Alligator mississippiensis. The Anatomical Record 307: 2953–2965. Crossref

Piras, P., Delfino, M., Del Favero, L., and Kotsakis, T. 2007. Phylogenetic position of the crocodylian Megadontosuchus arduini and tomistomine palaeobiogeography. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52: 315–328.

Santos, R.O., Wilkinson, M., and Zaher, H. 2025. An overview of the postcranial osteology of caecilians (Gymnophiona, Lissamphibia). The Anatomical Record, 1–26, https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.70000. Crossref

Schachner, E.R., Hedrick, B.P., Richbourg, H.A., Hutchinson, J.R., and Farmer, C.G. 2021. Anatomy, ontogeny, and evolution of the archosaurian respiratory system: A case study on Alligator mississippiensis and Struthio camelus. Journal of Anatomy 238: 845–873. Crossref

Skutschas, P.P. 2009. Re-evaluation of Mynbulakia Nesov, 1981 (Lissamphibia: Caudata) and description of a new salamander genus from the Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29: 659–664. Crossref

Skutschas, P.P. and Baleeva, N.V. 2012. The spinal cord supports of vertebrae in the crown‐group salamanders (Caudata, Urodela). Journal of Morphology 273: 1031–1041. Crossref

Wake, D.B. and Lawson, R. 1973. Developmental and adult morphology of the vertebral column in the plethodontid salamander Eurycea bislineata, with comments on vertebral evolution in the Amphibia. Journal of Morphology 139: 251–299. Crossref

Walter, J.D., Massonne, T., Paiva, A.L.S., Martin, J.E., Delfino, M., and Rabi, M. 2025. Expanded phylogeny elucidates Deinosuchus relationships, crocodylian osmoregulation and body-size evolution. Communications Biology 8: 611. Crossref

Wedel, M., Atterholt, J., Dooley, A., Farooq, S., Macalino, J., Nalley, T., Wisser, G., and Yasmer, J. 2021. Expanded neural canals in the caudal vertebrae of a specimen of Haplocanthosaurus. Academia Letters: art. 911. Crossref

Wilhite, R. 2023. A detailed anatomical study of M. Caudofemoralis Longus in Alligator mississippiensis. In: H.N. Woodward and J.O. Farlow (eds.), Ruling Reptiles: Crocodylian Biology and Archosaur Paleobiology, 80–99. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Crossref

Zippel, K.C., Lillywhite, H.B., and Mladinich, C.R.J. 2003. Anatomy of the crocodilian spinal vein. Journal of Morphology 258: 327–335. Crossref

Zverkov, N.G., Grigoriev, D.V., and Nikiforov, A.V. 2025. New polycotylid plesiosaur skeletons from the Upper Cretaceous of the Southern Urals provide additional diagnostic features of Polycotylus sopozkoi and demonstrate its variation. Historical Biology: 1–34. Crossref

William Jude Hart [williamjudehart@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-8322-2234 ], Department of Geology, Environment, and Sustainability, Hofstra University, 1000 Hempstead Tpke, Hempstead, NY 11549, USA.

Jessie Atterholt [jessie.atterholt@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1081-0552 ] and Mathew J. Wedel [Mathew.wedel@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6082-3103 ], College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific and Western University of Health Sciences, 309 E 2nd St., Pomona, CA 91766, USA.

Received 17 June 2025, accepted 16 October 2025, published online 10 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 W.J. Hart et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 749–753, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01269.2025