First record of the Eocene baleen whale Llanocetus outside Antarctica

FELIX G. MARX and HAMISH J. CAMPBELL

Baleen whales (mysticetes) diverged from toothed whales and dolphins around 36 Ma. Among the oldest fossils attesting to their origin is Llanocetus denticrenatus from the Eocene (ca. 34 Ma) of Seymour Island, Antarctica. Isolated teeth from the same area suggest the presence of a second, potentially much larger species, but no further material of either form has been found to date. Here, we report the first record of Llanocetus outside Antarctica, based on a fragmentary but highly diagnostic tooth from Chatham Island, New Zealand. The new find considerably broadens both the geographical and the latitudinal range of the genus and suggests caution in interpreting the interrelationships of the basalmost mysticetes.

Introduction

Modern baleen whales descend from toothed ancestors characterised by a surprising diversity of size and form (Fitzgerald 2010; Fordyce and Marx 2018; Hernández Cisneros and Velez-Juarbe 2025). Dental anatomy is particularly variable and marked by differences in tooth count, spacing, and relative size, as well as the number and arrangement of accessory denticles, enamel ornamentation, root morphology, and the overall degree of heterodonty (Hocking et al. 2017a; Peredo et al. 2018a). The interrelationships of basal mysticetes remain debated, as does the timing and functional context of the emergence of baleen (Deméré et al. 2008; Marx et al. 2016; Hocking et al. 2017a, b; Geisler et al. 2017; Fordyce and Marx 2018; Peredo et al. 2018b; Gatesy et al. 2022; Boessenecker et al. 2023; Marx et al. 2023; Hernández Cisneros and Velez-Juarbe 2025).

Despite the diversity of early mysticetes, fossils recording their origin during the late Eocene remain limited to just four occurrences worldwide: Mystacodon selenensis from the Paracas Formation (36.4 Ma) of Peru (Muizon et al. 2019); Fucaia humilis from the Lincoln Creek Formation (34.5 Ma) of Washington State, USA (Tsai et al. 2024); Llanocetus denticrenatus from the uppermost La Meseta/Submeseta Formation (34.2 Ma) of Seymour Island, Antarctica (Fordyce and Marx 2018); and three large isolated teeth of Llanocetus sp., also from Seymour Island and of approximately the same age as L. denticrenatus (Marx et al. 2019).

Llanocetus was the first Eocene mysticete to be reported (Mitchell 1989) and remained their only record from this epoch for nearly 30 years. Here, we report the first definite occurrence of this genus outside Antarctica, with implications for the biogeography and, perhaps, interrelationships of the earliest baleen whales.

Institutional abbreviations.—CIM, Chatham Islands Museum, Waitangi, Chatham Islands, New Zealand; IAA, Instituto Antártico Argentino, San Martín, Argentina; OU, Geology Museum, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand; USNM, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA.

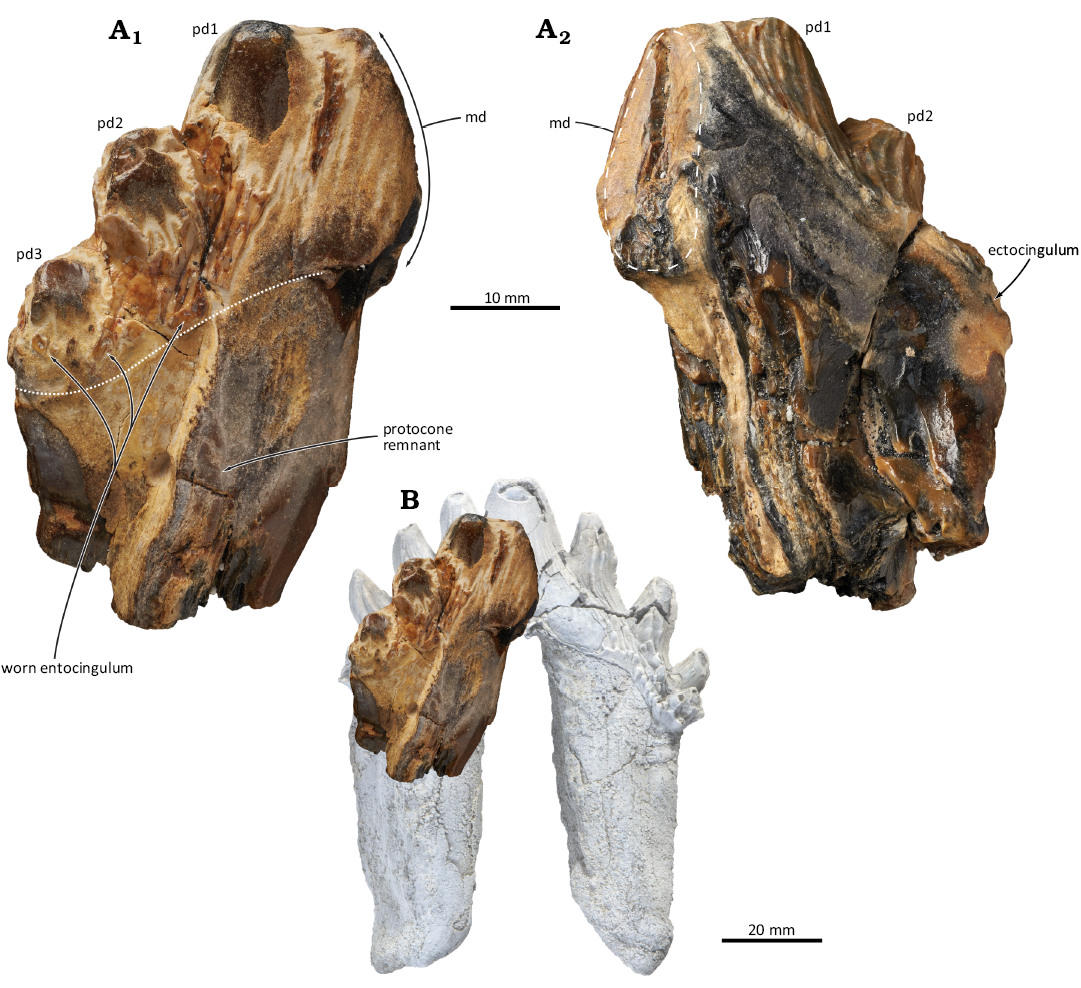

Other abbreviations.—md, main denticle; pd, posterior denticle.

Geological setting

The new fossil belongs to a collection of isolated finds gifted to the Chatham Islands Museum by local collector Bob Weston (Chatham Island, New Zealand). Its precise provenance is unknown. However, judging from the associated material and the prospecting habits of the collector, it was likely found on Maunganui Beach, between Cape Pattisson and Maunganui, on the north-western coast of Chatham Island. Regionally exposed Palaeogene rocks include the Paleocene–Eocene Tioriori Group (63–47 Ma), the Eocene Red Bluff Tuff and Te Whanga Limestone (55–35 Ma) and the Oligocene–Miocene Taoroa Limestone (25–20 Ma) (Campbell et al. 1993; Forsyth et al. 2008; Hollis et al. 2017).

Most of the sediment-derived cobbles and pebbles on the beach west of Maunganui originate from the Tioriori Group (Campbell et al. 1993). However, the latter is likely too old to have yielded the current find, with contemporaneous cetacean fossils generally being restricted to the Tethys (Bebej et al. 2015) and seemingly not reaching Zealandia until around 40 Ma (Köhler and Fordyce 1997; Marx and Fordyce 2015). Previously reported finds of Llanocetus and putatively related fossils from Peru and New Zealand date to the latest Eocene and earliest Oligocene (ca. 36–32 Ma; Fordyce and Marx 2018; Marx et al. 2019; Muizon et al. 2019). We therefore hypothesise that the new find from Maunganui Beach derives from the upper portion of the Te Whanga Limestone (Te One Member or undifferentiated equivalent; Campbell et al. 1993; James et al. 2011).

Material and methods

For the description of the tooth crown, we use the term “denticle” to account for uncertain homology with the cusps of other mammals.

Systematic palaeontology

Cetacea Brisson, 1762

Mysticeti Gray, 1864

Llanocetidae Mitchell, 1989

Llanocetus Mitchell, 1989

Type species: Llanocetus denticrenatus Mitchell, 1989. Seymour Island, Antarctica; near the top of unit Telm 7 of the La Meseta/Submeseta Formation.

Llanocetus sp.

Fig. 1.

Material.—CIM 2022.004.111, posterior portion of an isolated upper right premolar. Most likely Maunganui Beach between Cape Pattisson and Maunganui, Chatham Island NW coast. Probably Eocene Te Whanga Limestone.

Description.—CIM 2022.004.111 represents a third or fourth right upper premolar based on its relatively large size, the presence of a protocone remnant, and the lingual curvature of the crown in posterior view. The tooth has broken almost exactly in half along the centre of the main denticle, has lost the dorsal half of the posterior root, and shows considerable surface wear. As preserved, the crown measures 31 mm from its posterior border to the apex of the interradial space. Judging from the known upper premolar anatomy of Llanocetus, the complete crown would presumably have measured about twice that length. This makes it considerably larger than the only complete upper premolar of the holotype of Llanocetus denticrenatus (left P3, crown length = 42 mm), but similar to an isolated presumed left P3 of Llanocetus sp. (IAA Pv731, 65 mm) (Fordyce and Marx 2018; Marx et al. 2019).

In lingual view, the base of the crown steeply rises from the apex of the interradial space (Fig. 1). Only the base of the main denticle is preserved and suggests a robust structure about twice the size of the accessory denticles. There are three posterior denticles, all roughly comparable in their basal diameter (ca. 10 mm). The first posterior denticle (pd1) is located directly adjacent to, and partly merges into, the main denticle. Where preserved, the enamel bears well-marked dorsoventral ridges. Though worn, there are traces of an entocingulum dorsal to pd2 and especially pd3. The posterior root is broad mesiodistally and bears a deep sulcus running dorsally along the centre of its lingual face. The latter likely marks the point of fusion between two formerly separate posterior roots.

Fig. 1. A. Upper right premolar (CIM 2022.004.111) of the llanocetid mysticete Llanocetus sp. from Chatham Island, New Zealand. Photographs in lingual (A1) and labial (A2) views. White dotted line shows the base of the crown. B. CIM 2022.004.111 in lingual view overlaid on the photograph of an upper left premolar (IAA Pv731) previously referred to Llanocetus sp. (Marx et al. 2019). IAA Pv731 has been mirrored horizontally to match the orientation of CIM 2022.004.111. Abbreviations: md, main denticle; pd, posterior denticle.

In labial view, the enamel is covered by dorsoventral ridges, at times anastomosing, resembling those on the lingual side of the crown. Although all of the accessory denticles are broken, the orientation of the enamel ridges, especially on pd2, suggests that they were apically curved.

Remarks.—The new specimen closely matches Llanocetus in having a low, elongate, palmate crown with apically curved accessory denticles; ento- and ectocingula; strong lingual and labial enamel ornament; and completely unfused roots. It is larger than comparable teeth of Llanocetus denticrenatus, but matches isolated finds from Seymour Island, Antarctica, previously referred to Llanocetus sp. (see below). A largely undescribed Early Oligocene specimen from New Zealand (OU GS10897) has also been provisionally referred to Llanocetus (Fordyce 2003); however, it lacks the apical curvature of the accessory denticles and, pending more detailed comparisons, is here regarded as an indeterminate llanocetid.

Discussion and conclusions

Taxonomic implications.—Upon its description in 1989, Llanocetus denticrenatus was assigned to its own family, Llanocetidae, on account of its unusual dental anatomy (Mitchell 1989). The scope of this family has remained in flux, with studies variously restricting it—or the equivalent clade—to Llanocetus (Marx and Fordyce 2015; Muizon et al. 2019; Tsai et al. 2024), Llanocetus + Mystacodon (Hernández-Cisneros and Velez-Juarbe 2025), or some combination of Llanocetus + Mystacodon + other undescribed specimens from New Zealand (Fordyce and Marx 2018; Boessenecker et al. 2023).

Compared to all other toothed mysticetes, L. denticrenatus stands out for having small, widely spaced teeth relative to its body size (Fordyce and Marx 2018; Marx et al. 2019). If this trait characterised the genus as a whole, and on the assumption of isometry, large teeth like those from Antarctica and Chatham Island would indicate body lengths of up to 12 m, far in excess of the 8 m estimated for L. denticrenatus (Fordyce and Marx 2018; Marx et al. 2019).

Alternatively, it is possible that species of Llanocetus other than L. denticrenatus follow a tooth-to-body size pattern more consistent with that of other archaic mysticetes and basilosaurid archaeocetes. If so, the large teeth from Antarctica and Chatham Island may have belonged to animals measuring just 4.5 m in length (Marx et al. 2019) and, thus, only slightly larger than Mystacodon (3.75–4.0 m). The premolars of the latter remain incompletely known owing to extensive wear. Like Llanocetus, however, they appear to have completely unfused roots, a well-developed entocingulum, and strong enamel ornament at least on the lingual side of the crown (Muizon et al. 2019).

With Llanocetus now recorded deep inside the South Pacific, it is tempting to speculate that the teeth of Mystacodon indeed resembled those of Llanocetus, supporting previous notions of a close phylogenetic relationship. If so, this might call into question the idea of a gigantic form of Llanocetus. There is currently not enough information to test these possibilities but, based on CIM 2022.004.111, we predict that future finds from the Eocene of New Zealand will include either (i) skull fossils of a large species of Llanocetus or (ii) smaller fossils resembling Mystacodon. Either, perhaps in combination with better-preserved teeth of Mystacodon from Peru, would help to clarify the scope and interrelationships of Llanocetidae.

Biogeographical implications.—The occurrence of Llanocetus at roughly 43.8°S marks a notable range extension for this hitherto exclusively Antarctic genus (Fordyce and Marx 2018; Marx et al. 2019). Even so, it matches earlier studies that located the earliest (i.e., Eocene) phase of mysticete evolution in the Southern Hemisphere (Fordyce 1980; Steeman et al. 2009; Buono et al. 2019). This interpretation was recently challenged by the description of Fucaia humilis from the uppermost Eocene of Washington State, USA, which suggests a more widespread and ecologically disparate context for early baleen whale diversification (Tsai et al. 2024). This is a plausible scenario but requires further testing, as the holotype of F. humilis lacks associated age-diagnostic microfossils and has only been dated via magnetostratigraphy of presumably correlated strata located 2.8 km from the type locality. Interestingly, no Eocene mysticetes have yet been reported from the North Atlantic or Tethys, suggesting either a sampling gap or—considering the relatively long history of sampling in these regions—a genuine absence.

Acknowledgements.—We thank the late Bob Weston (Chatham Island, New Zealand) for finding the tooth and donating it to the Chatham Islands Museum; Alan Tennyson (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand) for help with its preliminary identification; and Monique Croon (CIM) for providing access to material under her care.

Editor: Eli Amson

References

Bebej, R.M., Zalmout, I.S., El-Aziz, A.A.A., Antar, M.S.M., and Gingerich, P.D. 2015. First remingtonocetid archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the middle Eocene of Egypt with implications for biogeography and locomotion in early cetacean evolution. Journal of Paleontology 89: 882–893. Crossref

Boessenecker, R.W., Beatty, B.L., and Geisler, J.H. 2023. New specimens and species of the Oligocene toothed baleen whale Coronodon from South Carolina and the origin of Neoceti. PeerJ 11: e14795. Crossref

Buono, M.R., Fordyce, R.E., Marx, F.G., Fernández, M.S., and Reguero, M.A. 2019. Eocene Antarctica: a window into the earliest history of modern whales. Advances in Polar Science 30: 293–302.

Campbell, H.J., Andrews, P.B., Beu, A.G., Maxwell, P.A., Edwards, A.R., Laird, M.G., Hornibrook, N., Mildenhall, D.C., Watters, W.A., Buckeridge, J.S., Lee, D.E., Strong, C.P., Wilson, G.J., and Hayward, B.W. 1993. Cretaceous–Cenozoic geology and biostratigraphy of the Chatham Islands, New Zealand. Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences Monograph 2: 1–269.

Deméré, T.A., McGowen, M.R., Berta, A., and Gatesy, J. 2008. Morphological and molecular evidence for a stepwise evolutionary transition from teeth to baleen in mysticete whales. Systematic Biology 57: 15–37. Crossref

Fitzgerald, E.M.G. 2010. The morphology and systematics of Mammalodon colliveri (Cetacea: Mysticeti), a toothed mysticete from the Oligocene of Australia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 158: 367–476.

Fordyce, R.E. 1980. Whale evolution and Oligocene Southern Ocean environments. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 31: 319–336. Crossref

Fordyce, R.E. 2003. Cetacean evolution and Eocene–Oligocene oceans revisited. In: D.R. Prothero, L.C. Ivany, and E.A. Nesbitt (eds.), From Greenhouse to Icehouse—The Marine Eocene–Oligocene Transition, 154–170. Columbia University Press, New York.

Fordyce, R.E. and Marx, F.G. 2018. Gigantism precedes filter feeding in baleen whale evolution. Current Biology 28 (1): 1670–1676.e2. Crossref

Forsyth, P.J., Barrell, D.J.A., and Jongens, R. 2008. Geology of the Christchurch area. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences 1:250,000 Geological Map 16. 67 pp. GNS Science, Lower Hutt.

Gatesy, J., Ekdale, E.G., Deméré, T.A., Lanzetti, A., Randall, J., Berta, A., El Adli, J.J., Springer, M.S., and McGowen, M.R. 2022. Anatomical, ontogenetic, and genomic homologies guide reconstructions of the teeth-to-baleen transition in mysticete whales. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 29: 891–930. Crossref

Geisler, J.H., Boessenecker, R.W., Brown, M., and Beatty, B.L. 2017. The origin of filter feeding in whales. Current Biology 27: 2036–2042.e2. Crossref

Hernández Cisneros, A.E. and Velez-Juarbe, J. 2025. Morphology of the toothed mysticete Fucaia goedertorum and a reassessment of Aetiocetidae (Cetacea, Mysticeti). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: e2436924. Crossref

Hocking, D.P., Marx, F.G., Fitzgerald, E.M.G., and Evans, A.R. 2017a. Ancient whales did not filter feed with their teeth. Biology Letters 13: 20170348. Crossref

Hocking, D.P., Marx, F.G., Park, T., Fitzgerald, E.M.G., and Evans, A.R. 2017b. A behavioural framework for the evolution of feeding in predatory aquatic mammals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 284: 20162750. Crossref

Hollis, C.J., Stickley, C.E., Bijl, P.K., Schiøler, P., Clowes, C.D., Li, X., and Campbell, H. 2017. The age of the Takatika Grit, Chatham Islands, New Zealand. Alcheringa 41: 383–396. Crossref

James, N.P., Jones, B., Nelson, C.S., Campbell, H.J., and Titjen, J. 2011. Cenozoic temperate and sub-tropical carbonate sedimentation on an oceanic volcano—Chatham Islands, New Zealand. Sedimentology 58: 1007–1029. Crossref

Köhler, R. and Fordyce, R.E. 1997. An archaeocete whale (Cetacea: Archaeoceti) from the Eocene Waihao Greensand, New Zealand. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17: 574–583. Crossref

Marx, F.G. and Fordyce, R.E. 2015. Baleen boom and bust: a synthesis of mysticete phylogeny, diversity and disparity. Royal Society Open Science 2: 140434. Crossref

Marx, F.G., Buono, M.R., Evans, A.R., Fordyce, R.E., Reguero, M., and Hocking, D.P. 2019. Gigantic mysticete predators roamed the Eocene Southern Ocean. Antarctic Science 31: 98–104. Crossref

Marx, F.G., Hocking, D.P., Park, T., Pollock, T.I., Parker, W.M.G., Rule, J.P., Fitzgerald, E.M.G., and Evans, A.R. 2023. Suction causes novel tooth wear in marine mammals, with implications for feeding evolution in baleen whales. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 30: 493–505. Crossref

Marx, F.G., Hocking, D.P., Park, T., Ziegler, T., Evans, A.R., and Fitzgerald, E.M.G. 2016. Suction feeding preceded filtering in baleen whale evolution. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 75: 71–82. Crossref

Mitchell, E.D. 1989. A new cetacean from the Late Eocene La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 46: 2219–2235. Crossref

Muizon, C. de, Bianucci, G., Martínez Cáceres, M., and Lambert, O. 2019. Mystacodon selenensis, the earliest known toothed mysticete (Cetacea, Mammalia) from the late Eocene of Peru: anatomy, phylogeny, and feeding adaptations. Geodiversitas 41: 401–499. Crossref

Peredo, C.M., Peredo, J.S., and Pyenson, N.D. 2018a. Convergence on dental simplification in the evolution of whales. Paleobiology 44: 434–443. Crossref

Peredo, C.M., Pyenson, N.D., Marshall, C.D., and Uhen, M.D. 2018b. Tooth loss precedes the origin of baleen in whales. Current Biology 28: 3992–4000.e2. Crossref

Steeman, M.E., Hebsgaard, M.B., Fordyce, R.E., Ho, S.Y.W., Rabosky, D.L., Nielsen, R., Rahbek, C., Glenner, H., Sorensen, M.V., and Willerslev, E. 2009. Radiation of extant cetaceans driven by restructuring of the oceans. Systematic Biology 58: 573–585. Crossref

Tsai, C.-H., Goedert, J.L., and Boessenecker, R.W. 2024. The oldest mysticete in the Northern Hemisphere. Current Biology 34: 1794–1800.e3. Crossref

Felix G. Marx [felix.marx@tepapa.govt.nz; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1029-4001], Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand; Department of Geology, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 55 Cable Street, Wellington 6011, New Zealand.

Hamish J. Campbell [h.campbell@gns.cri.nz; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6845-0126], New Zealand Institute of Earth Sciences (formerly Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences), 1 Fairway Drive, Avalon, Lower Hutt 5011, New Zealand.

Received 30 June 2025, accepted 31 October 2025, published online 1 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 F.G. Marx and H.J. Campbell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 705–708, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01271.2025