A new caridean shrimp fossil with exceptionally preserved organs from the Middle Jurassic of La Voulte-sur-Rhône, France

FLAVIEN LAGRANGE, DENIS AUDO, GILIANE P. ODIN, SAMMY DE GRAVE, VINCENT FERNANDEZ, KATHLEEN DOLLMAN, and SYLVAIN CHARBONNIER

Lagrange, F., Audo, D., Odin, G.P., De Grave, S., Fernandez, V., Dollman, K., and Charbonnier, S. 2025. A new caridean shrimp with exceptionally preserved organs from the Middle Jurassic of La Voulte-sur-Rhône, France. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 70 (4): 775–794.

We used propagation phase contrast synchrotron X-ray micro-computed tomography (PPC-SRµCT) on an exceptionally preserved fossil caridean from the Callovian of the La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte. The tomographic data reveal the shape of the mandible and pereiopodal epipods allowing the description of a new genus and species of Acanthephyridae (Caridea) shrimp, Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. Most organs are exceptionally preserved in either mineral denser to X-ray than matrix, interpreted to be sulfides, or in mineral of lower density than the matrix, interpreted as carbonate/phosphate such as fluorapatite. We herein propose a taphonomic scenario for the preservation of M. polyphaga gen. et sp. nov.: it died from unknown causes not caused by an injury, as no wound is visible, falling on the sediment/water interface, it laid on its right side, and was probably covered by sediments and/or a microbial mat, thus quickly becoming entombed in the anoxic zone of the sedimentary column. Once there, many anatomic structures were replaced by phosphates. Sulfides precipitated concomitantly or quickly afterwards, probably aided by both internal and external source of metal ions. The importance of the external source of metal ions (hydrothermalism) is clear due to the prevalence of sulfides in the ventral side of the specimen, an area more permeable due to its abundance in thin membranes prone to decay. The loss of integrity thereafter led to sediment invading the body cavity, thus obliterating a few ventral anatomic details, including some pereiopodal muscles, part of the hepatopancreas, most of the gills, and possibly reproductive organs. The nodule was then formed, closing the system, and protecting the specimen from further diagenetic degradation.

Key words: Crustacea, Caridea, synchrotron, tomography, anatomy, Konservat-Lagerstätte, Callovian, Middle Jurassic.

Flavien Lagrange [flavien.lagrange@edu.mnhn.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3342-9829 ], Denis Audo [denis.audo@edu.mnhn.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3486-3552 ] (corresponding author), and Sylvain Charbonnier [sylvain.charbonnier@mnhn.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2343-6897 ], Centre de recherche en Paléontologie-Paris (CR2P), MNHN, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France.

Giliane P. Odin [giliane.odin@univ-eiffel.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8311-7666 ], Laboratoire Géomatériaux et Environnement (LGE), Université Gustave Eiffel, Marne-la-Vallée, France.

Sammy De Grave [sammy.degrave@oum.ox.ac.uk; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2437-2445 ], Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PW, UK.

Vincent Fernandez [vincent.fernandez@esrf.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8315-1458 ] and Kathleen Dollman [dollman@esrf.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5468-4896 ], European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Beamline BM18, 71 rue des Martyrs, 38000 Grenoble, France.

Received 16 July 2025, accepted 17 September 2025, published online 15 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 F. Lagrange et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Decapod crustaceans are a highly diverse group of animals (Martin and Davies 2001), yet, their fossil record is comparatively poor (Bishop 1986; Krause et al. 2011; Klompmaker et al. 2017). Indeed, with the exception of some heavily biomineralized pieces of exoskeleton such as the claws of ghost shrimps (Hyžný and Klompmaker 2015), crabs (Plotnick and McCarroll 2023), and pistol shrimps (Hyžný et al. 2017), as well as cephalothoracic shields, notably those of crabs and spiny lobsters, the fossilization potential of their soft tissues is relatively poor (Klompmaker et al. 2019, 2023). Consequently, a significant proportion of decapod diversity is only known from Konservat-Lagerstätten, outcrops where peculiar deposition settings such as a rapid burial of remains, anoxia, lack of scavengers and bioturbation allow for the preservation of crustacean remains in exquisite details (Jauvion 2016, 2020a; Xing et al. 2021; Klompmaker et al. 2023). However, even within these Konservat-Lagerstätten, preservation is usually limited to exoskeletons in anatomical connection (i.e., with exoskeleton elements still connected so close they seem still articulated) and occasionally, fossilised muscles (Klompmaker et al. 2019).

The Konservat-Lagerstätte of La Voulte-sur-Rhône (south-east France), dated to the Middle Jurassic (Callovian, ca. 165 million years; Elmi 1967), is a notable exception. This site is renowned for the rapid mineralization of arthropod remains in fluoroapatite, pyrite, galena, and sphalerite, which results in the preservation of animal remains at tissue level. This preservation often includes delicate organs such as the gonads, digestive gland, green gland, eyes, as well as the cardiac and nervous systems, in addition to muscles and cuticle (Secrétan 1983; Wilby et al. 1996; Jauvion et al. 2016, 2020a, b; Vannier et al. 2016; Audo et al. 2019; Charbonnier et al. 2024).

In the present research, we investigate a new specimen of caridean shrimp using propagation phase contrast synchrotron X-ray micro computed tomography (PPC-SRµCT). Carideans are relatively rare in the fossil record, and, so far, only one compressed specimen from the Eocene of Messel (Mazancourt et al. 2022) was known to preserve fossilised soft parts. The new exceptionally preserved specimen studied herein presents a complete digestive system, muscles, nervous system and excretory glands. These features allow us to describe a new species and focus on its palaeoecology. We also obtain some insights on the taphonomy of arthropods in La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte and propose a taphonomic scenario for the specimen, from the distribution of high- and low-density minerals replacing the original organs.

Institutional abbreviations.—ESRF, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France; MNHN, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France; OSUG, Observatoire des Sciences de l’Univers de Grenoble, France.

Other abbreviations.—a1, antennula; a2, antenna; b1, hepatic groove; e1e, cervical groove; hc, hepatic carina; hs, hepatic spine; mx1, maxillula; mx2, maxilla; mxp1–3, maxillipeds 1–3; P1–5, pereiopods 1–5; phc, posterior hepatic carina; pl1–5, pleopods 1–5; s1–6, pleonites 1–6.

Nomenclatural acts.—This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains, have been registered in Zoobank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D04FFF18-A7A2-4542-BC29-BE0E1D0D4A12.

Geological setting and associated fauna

The La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte is located in eastern France, on the right bank of the Rhône river. It was deposited on a passive margin of the southeastern basin, in an area rich in faults forming several sets of tilted blocks. As such, the palaeotopography was quite steep (Charbonnier et al. 2007; Charbonnier 2009). More precisely, the geological context, sponges from the nearby Ravin du Chenier and the fauna from the Konservat-Lagerstätte itself both point to a marine deep-water origin for the Konservat-Lagerstätte (Charbonnier et al. 2007).

The outcrop was discovered underneath rich iron ore deposits (up to 15 m thick) which were mined from Antiquity until 1892. The first exceptionally preserved fossils were mentioned by Fournet (1843), who noted the presence of fully articulated ophiuroids. Later, Gevrey (1899) mentioned the presence of numerous pyritized crustaceans in nodules among which he identified eryonids (polychelidans), erymids, and shrimps, that he compared to the then already well-known Solnhofen (Kimmeridgian–Tithonian) and Holzmaden (Toarcian) crustacean faunas. Later works in the early 20th century, in the 1980’s, as well as more recent works, have shown La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte to be extremely diverse. So far, it has yielded arthropods (crustaceans, thylacocephalans, pycnogonids); mollusks (cephalopods, bivalves), polychaete annelids, brachiopods, echinoderms (ophiuroids, asteroids, crinoids, echinoids), hemichordate worms, and rare vertebrates (actinopterygians, coelacanths, crocodilians) (Charbonnier et al. 2014).

The crustacean fauna is dominated by polychelidan lobsters and dendrobranchiate shrimps, but it also includes erymids, lophogastridans, mysidaceans, cumaceans, and two species of Udora Münster, 1839: Udora gevreyi Van Straelen, 1923, U. minuta Van Straelen, 1923. Udora was initially considered to be a caridean (Van Straelen 1923), but was reassigned to Procaridoidea Felgenhauer & Abele, 1983, by Schweitzer et al. (2010). The present study thus contributes to the increased biodiversity from La Voulte.

Material and methods

The present study is based upon a single specimen, MNHN. F.A58277, a caridean shrimp preserved within a carbonate nodule (Fig. 1A1–A3). This specimen was collected in the lower Callovian (Gracilis Ammonite Biozone) horizon of La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte (Ardèche, France). The shrimp was partially prepared to be visible outside its nodule long before this study was carried out, leading to the loss of some parts of the shrimp.

For comparative purposes, we examined tomographic data of five other crustaceans in La Voulte’s nodules, used in previous studies (Audo 2014; Jauvion et al. 2016, 2020a; Audo et al. 2019; Charbonnier et al. 2024): a female of Eryma ventrosum (Meyer, 1835) (OSUG-ID11544), a male of Eryma ventrosum (OSUG-ID11543), the holotype of Voulteryon parvulus Audo et al., 2014 (female, MNHN.F.A29151), the holotype of Palaeopolycheles nantosueltae Jauvion et al., 2020a (female, MNHN.F.A58254), and the specimen MNHN.F.A29521 of Willemoesiocaris ovalis (Van Straelen, 1923).

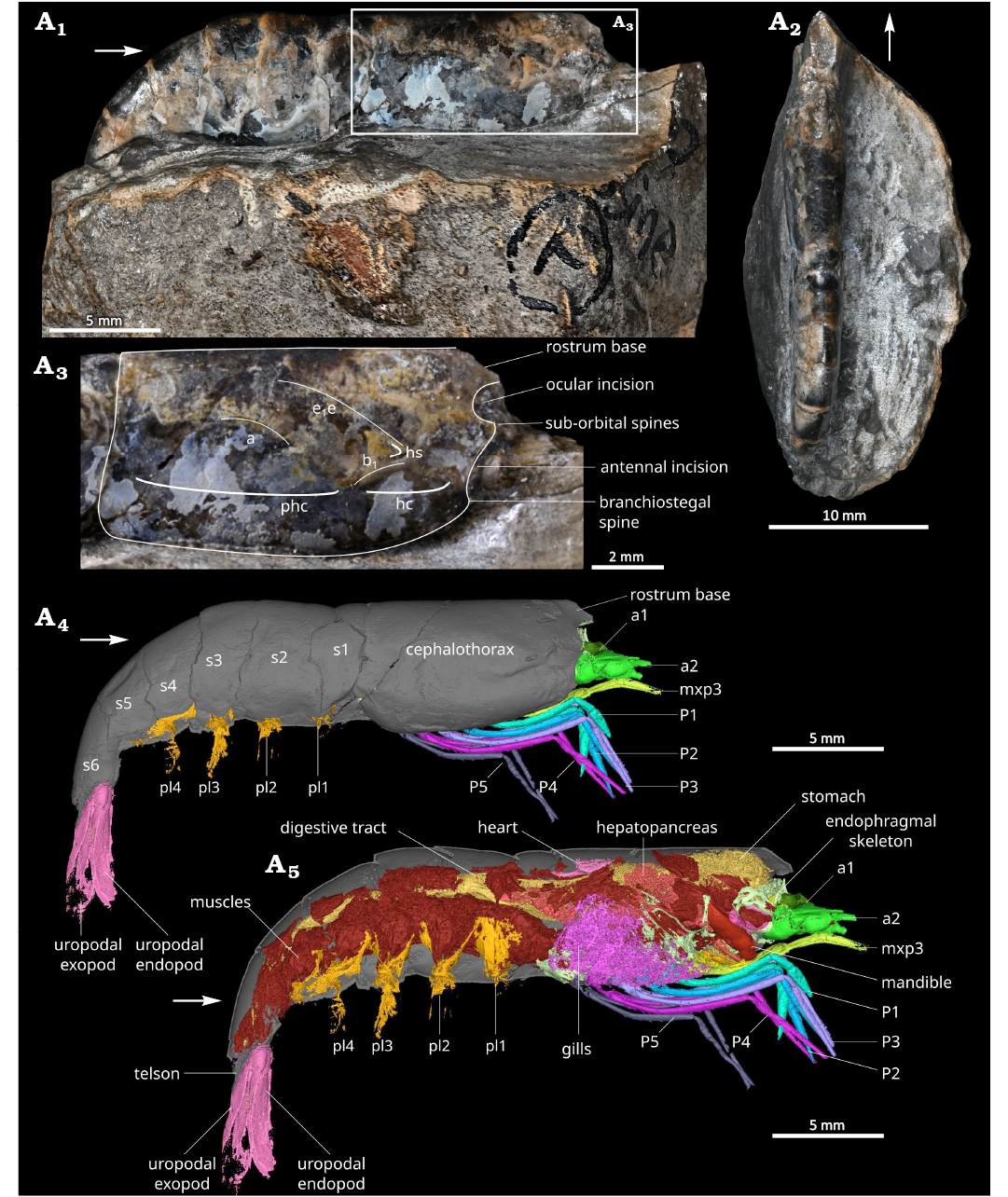

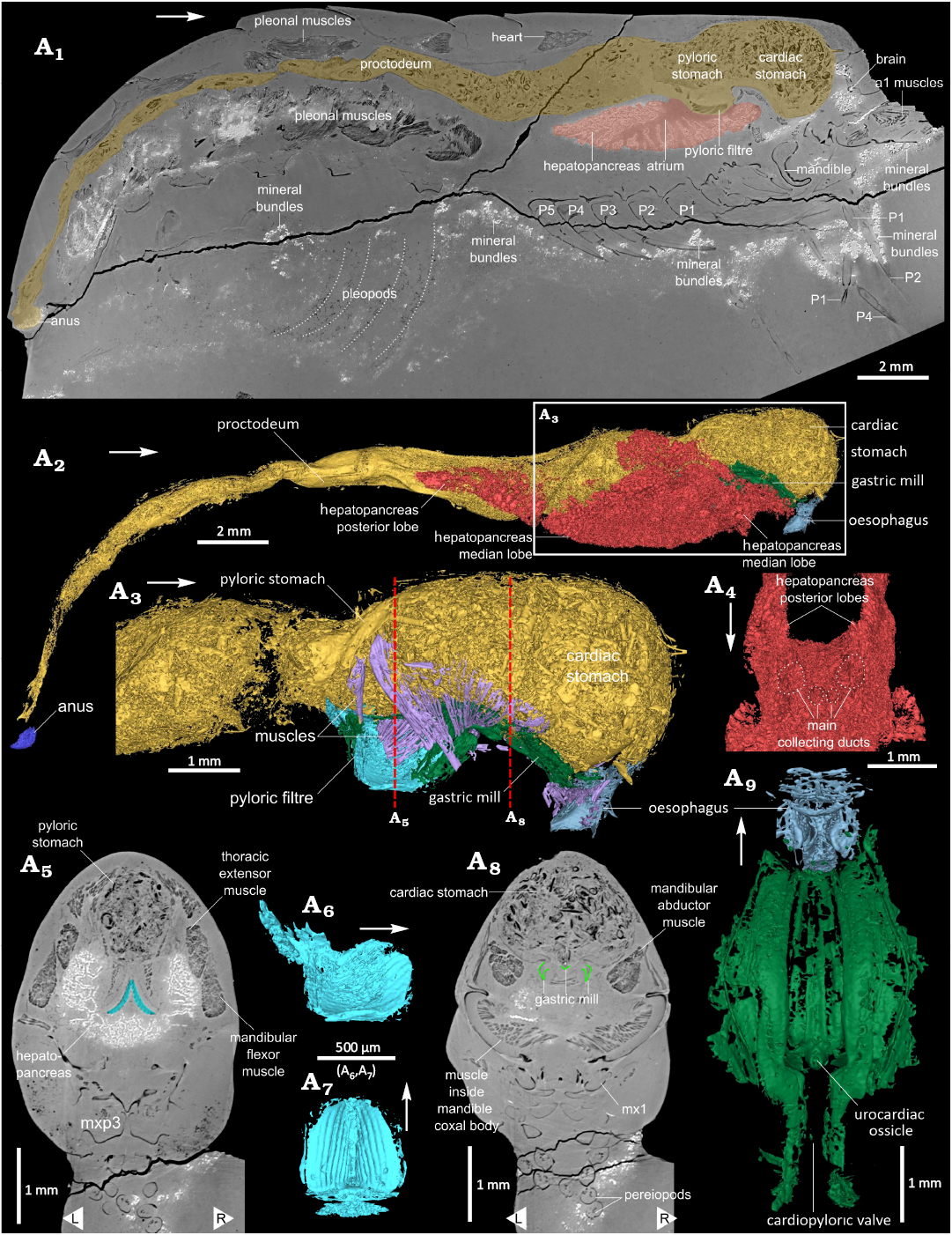

Fig. 1. Overview of the caridean shrimp Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. Specimen in right lateral (A1) and dorsal (A2) views. Cephalothorax in right lateral view (A3). 3D reconstruction of the holotype in right lateral view (A4), exposing the organs (A5). Abbreviations: a, branchiocardiac groove; a1, antennula; a2, antenna; b1, hepatic groove; e1e, cervical groove; hc, hepatic carina; hs, hepatic spine; mxp3, third maxilliped; phc, posterior hepatic carina; P1–5, pereiopods 1–5; pl1–4, pleopods 1–4; s1–6, pleonites 1–6. White arrows point to the front of the animal.

Dataset acquisition with ESRF synchrotron.—MNHN.F.A 58277 was imaged at the BM18 beamline of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) using propagation phase contrast synchrotron X-ray micro-computed tomography (PPC-SRµCT). The beamline was setup for a filtered white beam using the 1.56 T central pole of the tri-pole wiggler, with 0.44 mm of Molybdenum, 15 mm of SiO2, 59.3 mm of glassy carbon and 7.5 mm of Sapphire, resulting in a total integrated detected energy of 96.7 keV. The sample detector distance was set to 4 m. The indirect detector comprised a LuAG:Ce 250 µm scintillator, visible light lenses set for 1× magnification, and an Iris 15 sCMOS camera (Teledyne Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA), resulting in a measured isotropic pixel size of 4.007 µm. The usable field of view was (vertical×horizontal): 1856×4944 pixels, corresponding to 7.424×19.776 mm2. To compensate for the limited vertical field of view, 8 acquisitions were performed, moving the sample by 3.712 mm (50% of the vertical field of view) between each acquisition. Each acquisition consisted of 6000 projections recorded over a 360° rotation, each saved projection having an exposure time of 120 msec., resulting from the accumulation of 3 images of 40 msec. Raw acquired data are available publicly (Audo et al. 2025). Before the tomographic reconstruction, projections were stitched on the vertical axis following the protocol described in Benoit et al. (2020) to reduce imaging artefacts, generating a new dataset with projection of 8342×4944 pixels (v×h). The tomographic reconstruction was done using the single distance phase retrieval approach of PyHST2 (Mirone et al. 2014; Paganin et al. 2002), resulting in a 32-bits stack. Normalization of artifactual grey-level gradients and metallic inclusions was applied on the 32-bits stack (Cau et al. 2017), followed by various post-processing computation including: ring correction (Lyckegaard et al. 2011), conversion to 16-bit using the 0.001% saturation values from the whole 3D histogram of the stack, rotation of the images and cropping of the volume, binning 2×2×2 resulting in a dataset with an isotropic voxel size of 8.014 µm.

Several Matlab codes used for this processing are available at https://github.com/HiPCTProject/Tomo_Recon

Visualisation and segmentation of the dataset.—The dataset was reoriented and cropped to reduce its total size with the software Fiji (Schindelin et al. 2012), leading to a 3516×1847×536 voxels dataset. The dataset was visualised with Fiji and segmented with Mimics research, version 26.0 (Copyright Materialise). The various 3D segmentations of anatomical elements were then exported as STL files and visualised and measured in Meshlab (Cignoni et al. 2008).

Interpretation of PPC-SRµCT.—To avoid damaging this unique specimen, no section or chemical analyses were performed. The mineral composition of the fossil is interpreted based on the studies of other fossils from La Voulte published in Wilby et al. (1996) and Jauvion et al. (2020b).

Interpretation of anatomy.—Anatomy was partly interpreted based on Wicksten (2010). The inner skeleton components were interpreted following Rayner (1965) and Secrétan-Rey (2002); interpretation of muscles follows Schmidt (1915) and Vogt (2002).

Systematic palaeontology

Phylum Arthropoda Gravenhorst, 1843

Subphylum Crustacea Brünnich, 1772

Class Malacostraca Latreille, 1802

Superorder Eucarida Calman, 1904

Order Decapoda Latreille, 1802

Suborder Pleocyemata Burkenroad, 1963

Infraorder Caridea Dana, 1852a

Superfamily Oplophoroidea Dana, 1852b

Family Acanthephyridae Spence Bate, 1888

Genus Mandocaris nov.

ZooBank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:525AED83-0019-415D-82 D1-6182615231BD.

Etymology: A combination of the Latin mando, glutton and caris, shrimp. Referring to the holotype’s stomach and digestive system completely full of prey fragments, a rarity. The gender of the genus is feminine.

Type species: Mandocaris polyphaga sp. nov., by monotypy; see below.

Diagnosis.—As for monotypic type species.

Remarks.—Mandocaris gen. nov. clearly possesses a saddle-shaped tergopleuron of pleonite 2, covering that of pleonites 1 and 3, clawed pereiopods 1–2 (Fig. 1), and non-chelate pereiopods 3–5 (Fig. 2). This combination of characters unequivocally places Mandocaris gen. nov. in Caridea (see Holthuis 1993).

Although many characters traditionally used to differentiate the families are lacking in the fossil, several key characters allow us to assign Mandocaris gen. nov. to Acanthephyridae. Primarily, amongst these are the structure of the epipods on pereiopod 1 (Fig. 2) and the morphology of the mandible (Fig. 3). It is noteworthy that only two families, Oplophoridae Dana, 1852a, and Acanthephyridae, exhibit epipods terminating in a vertical appendix which extends into the branchial chamber. While some classifications (e.g., Chace 1992; Bracken et al. 2009; Wong et al. 2015) consider these two families to be a single one, we here adhere to the two-family concept outlined in Chan et al. (2010), De Grave and Fransen (2011), and Lunina et al. (2024).

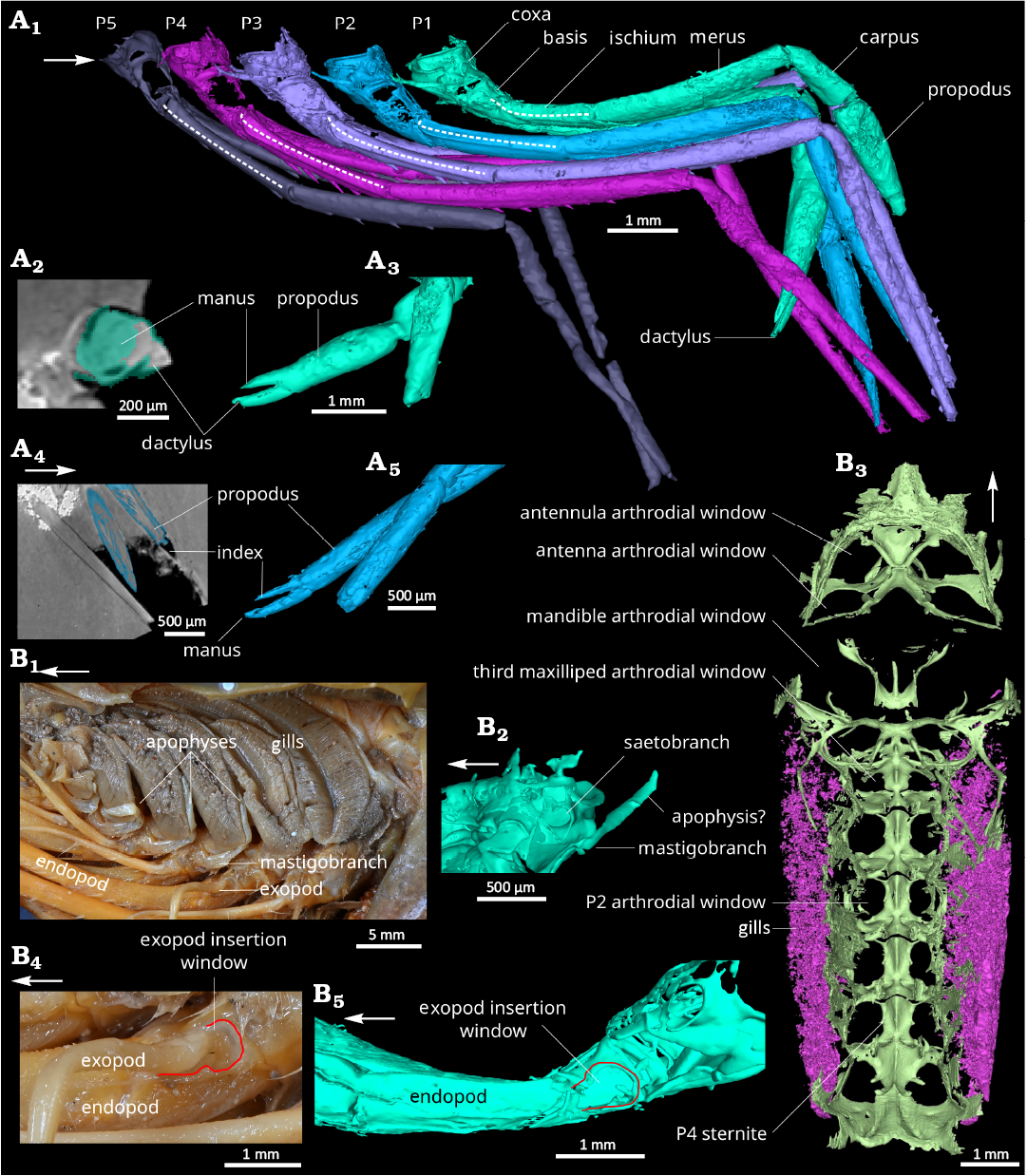

Fig. 2. Comparison of pereiopods, branchial cavity and endophragmal/epimeral skeleton of the caridean shrimps. A. Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. 3D model of pereiopods in right lateral view (A1). Claws of the pereiopod 1: coronal slice (A2) and 3D reconstruction (A3); claws of the pereiopod 2: sagittal slice (A4); and 3D reconstruction (A5). B. Extant Acanthephyra armata Milne-Edwards, 1881 (MNHN-IU-Na.10498), 450–480 m deep, near Toliara, Madagascar. Modern, branchial cavity in left lateral view (B1); 3D model of the base of the left pereiopod 1, mastigobranch-setobranch complex (B2); 3D model of the endophragmal and epimeral cephalothoracic skeleton (light green) and gills (pink) (B3); base of the pereiopod 4 (B4) and 1 (B5) in left lateral view (note the similarities). Abbreviations: P1–5, pereiopods 1–5. White arrows point to the front.

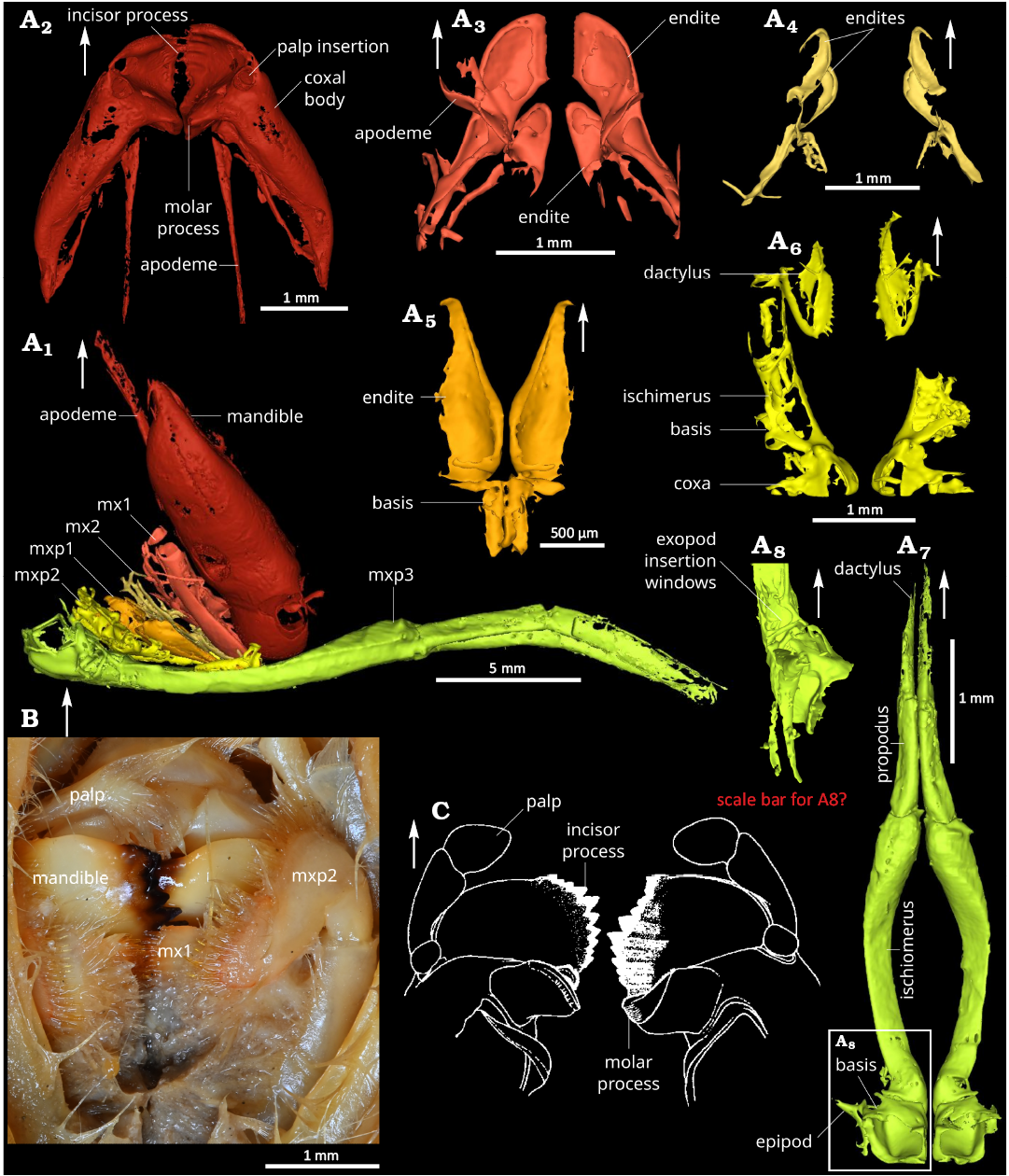

Although the presence and shape of the mastigobranchs unequivocally places Mandocaris gen. nov. in the superfamily Oplophoroidea, assigning the genus to one of the two constituent families is more problematic. The only available definition for the families (Lunina et al. 2024) only uses characteristics of the mouthparts to define them; these particular features are not preserved in sufficient detail in the material at hand. Although strong genetic evidence is presented in Chan et al. (2010), combined with ecological differences to keep both families separate, morphological support is scant. Neither Chan et al. (2010), nor the earlier work by Chace (1986) in which all known genera are outlined, offers much resolution to morphologically distinguish both families. However, the shape of the corpus of the mandible (Fig. 3) appears diagnostic between both families, especially the molar process. In the known genera of Oplophoridae, a deep channel is present on the molar, flanked by very thin walls (Chace 1986; Chan et al. 2010). In contrast, this appears to be lacking in all known Acanthephyridae genera. Mandocaris gen. nov. appears to be lacking this deep channel, and in view of the similarity of the mandible of Mandocaris gen. nov. to modern Acanthephyridae, the genus is herein tentatively assigned to that family.

Acanthephyridae is a deep-water, mainly benthopelagic or benthic clade of shrimps, usually occurring below 1000 m (Chan et al. 2010). Thus, its presence in La Voulte is congruent with the modern interpretation of the bathyal palaeoenvironment by Charbonnier et al. (2007) (see also Charbonnier 2009).

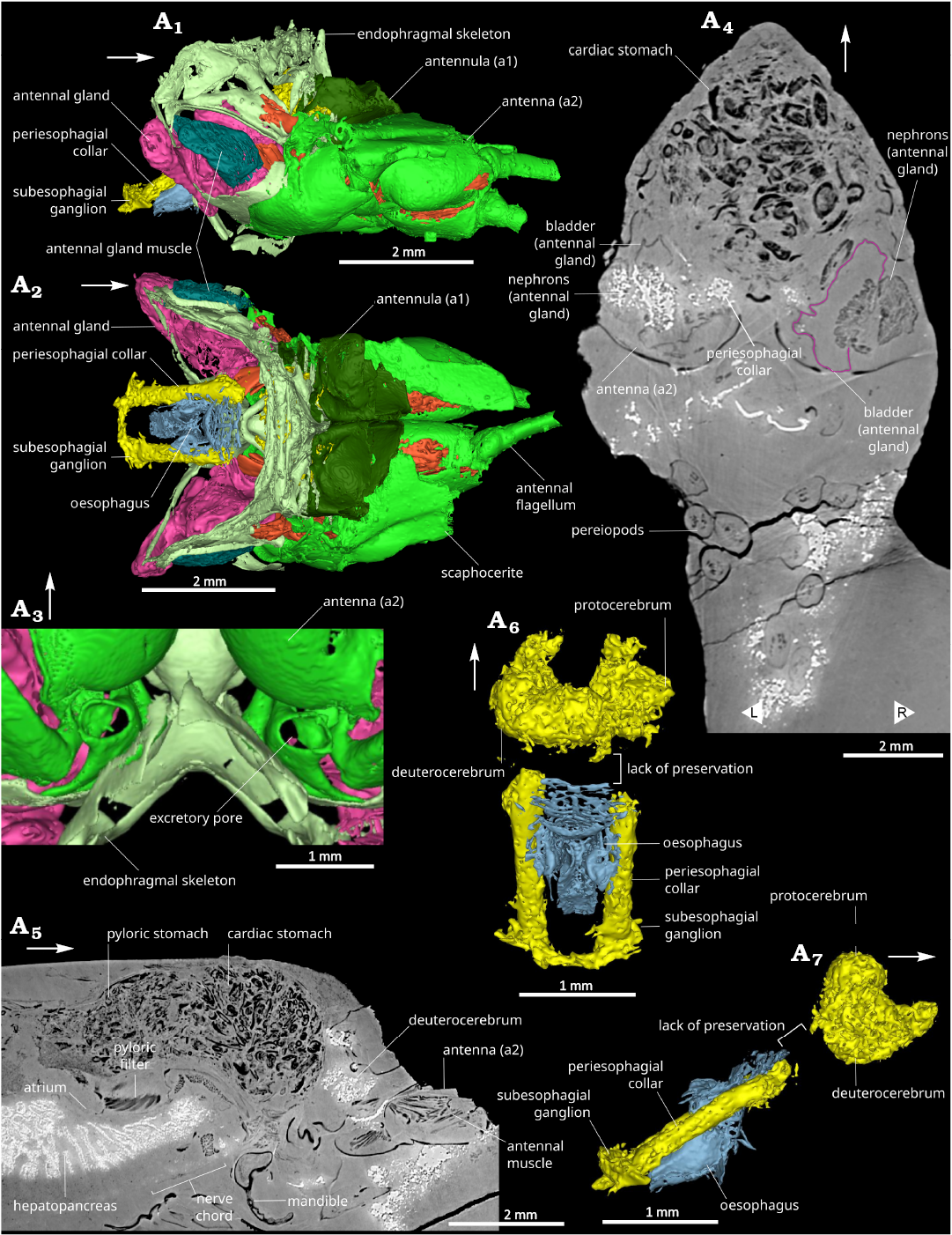

Fig. 3. Anterior part of caridean shrimp Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France, showing antennulae, antennae, excretory and nervous systems. 3D model of cephalic area in right lateral (A1) and dorsal (A2) views. 3D model of the base of the antennae in ventral view, showing excretory pore (A3). Coronal slice at the level of the antennae and the green glands (A4). Sagittal view showing part of the nervous system (A5), cephalic neural system in dorsal (A6) and lateral (A7) views. White arrows point to the front. L/R, left/right.

Within Acanthephyridae, Mandocaris gen. nov. differs from all other genera by its cephalothoracic shield being mostly smooth, with shallow grooves, without visible branchiostegal spine, with a smooth dorsal margin, and the smooth median line of each pleonite (Fig. 1). In contrast, other Acanthephyridae genera tend to have a spinose cephalothorax and distinct carinae on the median line of the cephalothorax and pleonites. As Mandocaris gen. nov. is the oldest known Acanthephyridae known to date, its overall lack of spines may be explained if Mandocaris gen. nov. is an early offshoot of Acanthephyridae and if this set of characters appeared later within Acanthephyridae.

Compared to other crustacean genera from La Voulte-sur-Rhône, Mandocaris gen. nov. possesses a saddle-shaped second pleonite similar to Udora. It differs from the holotypes of Udora minuta (OSUG-ID.1796) and Udora gevreyi (OSUG-ID.1794) (both known from La Voulte) by the presence of the branchiostegal and hepatic carinae, and longer pleonites 5–6. Other characters may also differ, but the fragmentary preservation of the holotypes of these species limits how much they can be compared. If we consider Udora to be a procarididean, then Mandocaris gen. nov. is currently the only known caridean from La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—As for the monotypic type species.

Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov.

Figs. 1–8.

ZooBank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:146D433F-342B-4504-BE3 A-CF62A5D5B13A.

Etymology: From the Latin polyphagus, big eater; alluding to the digestive system full of food fragments.

Holotype: MNHN.F.A58277, a small nodule excavated to show the cephalothoracic shield and pleon of the shrimp.

Type locality: Ravin des mines, La Voulte-sur-Rhône, Ardèche, France.

Type horizon: Macrocephalites gracilis Ammonite Biozone, early Callovian (Elmi 1967).

Material.—Holotype only.

Diagnosis.—Cephalothorax and abdomen dorsally non carinate; branchiostegal carina distinct, branchiostegal and hepatic spine lacking; hepatic groove distinct, other grooves indistinct or missing; tergopleuron of pleonite 2 saddle-shaped, covering both tergopleura of pleonites 1 and 3; pleonite 6 twice as long as high; mandibles slightly dissimilar, molar and incisor fused, molar process compressed, distal surface triangular, incisor process dentate along entire margin; mandibular palp articulation present; strap-like epipod of pereiopod 1 (P1; thoracopod 4) likely with endpiece extending perpendicularly into branchial chamber; epipodites of pereiopods 2–5 (P2–5; thoracopods 5–8) likely similar based on insertion area of epipod; pereiopods with ischium and merus not broadly compressed; pereiopod 1 and 2 with subequal, well-developed chelae and undivided carpus; chelae of pereiopod 1 and 2 simple in form and ornamentation, a short and straight manus, and straight dactyl, longer than manus.

Dimensions.—Total body length around 32 mm long from the ocular incision to the tip of the telson (calculated by adding the different tergite lengths as the specimen is curved). Cephalothorax: 10.7 mm long (around 1/3 of total length), 5.6 mm in height, 4.1 mm wide (Fig. 1).

Description.—Outline of the cephalothorax (Fig. 1A3): Cephalothorax subrectangular in outline in lateral view, about 2.5 times longer than wide; cephalothorax dorsal margin straight and smooth (without spine or carina); ocular incision wide and relatively shallow, strengthened by a thin carina; double infraorbital spine, one above the other, intercalated between ocular incision and antennal incision; antennal incision very wide and shallow; pterygostomial spine small; ventral margin convex, strengthened by a smooth, raised, carina; cephalothorax posterior margin straight; rostrum broken, probably short based on the shape of its remaining proximal portion; shallow cervical, hepatic, and branchiocardiac grooves; hepatic carina clearly visible, most prominent feature of the surface; visible posthepatic carina; cephalothoracic exoskeleton smooth.

Pleon and telson (Fig. 1): Unfolded length estimated to be 14.3 mm, 1.3 times longer than cephalothoracic shield; small first pleonite (s1), with tergopleuron laterally partially covered by the cephalothoracic shield anteriorly and s2 tergopleuron posteriorly; second pleonite (s2) larger than s1, with saddle-shaped tergopleuron partially covering that of s1 and s3 (Fig. 1A4); third pleonite (s3) subrectangular in outline in lateral view, smaller than s2; fourth pleonite (s4) subtrapezoidal in outline in lateral view, similar in size to s5; fifth pleonite (s5) subtrapezoidal in outline in lateral view, similar in size to s4; telson broken.

Eyes and cephalic appendages (Figs. 3, 4): Base of ocular peduncle in connection with endophragm, most of the eye broken; antennula with basis subtriangular in section, the rest not visible or broken (Fig. 3A1, A2); antennal coxa very small, subtriangular in outline in ventral view, with a nephropore occupying most of its ventral surface (Fig. 3A3); antennal basis wide, subtriangular in outline in ventral view, acuminate distally, largest podomere of the antenna after the scaphocerite; scaphocerite flat, with a median carina, broken distally; antennal endopod ischium subtriangular in outline in ventral view, smaller than basis but larger than merus; antennal endopod merus subtriangular in outline in ventral view, acuminate distally, smaller than all other a2 podomeres except a2 coxa; antennal endopod carpus subcylindric, tapering in width distally, slightly smaller than basis, carrying a multiarticulated flagellum (broken); mandible formed of a coxal body with incisor and molar processes, carrying a palp (Fig. 4A1, A2); mandibular coxal body large, 4 mm long, subtriangular in outline in ventral view, with an hemicircular axial section, filled with muscles, mesially forming a hemicircular incisor process fused to the molar process, both processes separated from the rest of the coxal body by mesial narrowing; with an apodeme connecting the muscles in the cephalothorax to a point near the junction between the main part of the coxal body and the incisor and molar processes; incisor process located ventrally, concave dorsally, convex ventrally, fused to molar process, with its axis perpendicular to molar process axis, composed of a wide serrated blade (Fig. 4A2); mandibular molar process located dorsally, forming a single tooth (Fig. 4A2); palp not preserved, insertion dorsally to the anterior edge of the incisor process; maxillula (mx1) forming two sutriangular lobes (endites), anterior one framing the smaller posterior one, both with straight occlusal margins, anterior lobe occlusal margin with small spine-like structures, probably setae (Fig. 4A3); maxilla (mx2) forming two subtriangular lobes (endites), the anterior one framing the posterior one, both with straight occlusal margins, possibly also forming a third lobe (endite) posterior to the others (Fig. 4A4; poorly preserved).

Fig. 4. Comparison of mouthparts of the caridean shrimps. A. Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. Lateral view of all mouthparts (A1). Dorsal views of mandibles (A2), maxillula (A3), maxilla (A4), base of the maxilliped 1 (A5), maxilliped 2 (A6), maxiliped 3 (A7). Left lateral view of the base of the maxilliped 3 (A8). B. Photograph of Acanthephyra armata Milne-Edwards, 1881 (MNHN-IU-Na.10498) 450–480 m deep, near Toliara, Madagascar, modern, mouthparts in ventral view. C. Drawing of Acanthephyra stylorostratis (Spence Bate, 1888), mandibles in dorsal view (modified from Chace 1986); not to scale. White arrows point to the front. Abbreviations: mx1, maxillulae; mx2, maxillae; mxp1–3, maxillipeds 1–3.

Thoracic appendages (Figs. 2, 4): Maxilliped 1 (mxp1, thoracopod 1), smallest maxilliped, two parts preserved, posterior one subrectangular and narrow, anterior one subrectangular proximally, acuminate distally (Fig. 4A5); maxilliped 2 (mxp2, thoracopod 2), relatively long, about 1/3 of carapace length (Fig. 4A6); maxilliped 3 (mxp3, thoracopod 3), longest of the maxillipeds, 8.2 mm, overreaching to the antennal flagellum base, pediform, biarmed (Fig. 4A7); mxp3 coxa short, subquadrate in outline in ventral view, with the largest mastigobranch of all other appendages (epipod, larger as the rest of the coxa); mxp3 basis subtriangular, with a small articulation (Fig. 4A8) for an exopod (not preserved); mxp3 ischiomerus slender, curved, concave dorsally, convex ventrally, longest podomere of the maxilliped; mxp3 carpus elongated, subrectangular in outline in ventral view, with a triangular axial section, propodus fused to dactyl, with subrectangular outline in lateral view, laterally flattened; shape of pereiopods 1–5 (thoracopod 4–8) and their individual podomeres allowing the pereiopods to the closely packed together under the cephalothorax (Fig. 2A1); pereiopod 1 (P1, thoracopod 4) shortest of the pereiopods, smooth, chelate; P1 coxa short, wider than long, carrying setobranch and mastigobranch with a short apophysis (?) (Fig. 2B2); P1 basis subtrapezoidal in outline in lateral view, tapering proximally, twice longer than coxa, with an exopod insertion window (Fig. 2B5); slender P1 ischium, subrectangular in outline in lateral view, as long as basis, with a thin outer lateral carina; merus slender twice longer than ischium, tapering proximally; P1 propodus wide, with slightly convex margins, almost as long as merus, 2/3 of it represented by the palm, rest by pointed manus (Fig. 2A3); P1 dactylus slightly longer than manus, straight, with a very slightly curved distal portion (Fig. 2A3); pereiopod 2 (P2, thoracopod 5) slightly slenderer than P1 (Fig. 2A1), smooth, chelate; P2 coxa short, wider than long, with a setobranch and mastigobranch; P2 basis subtrapezoidal in outline in lateral view, tapering proximally, twice longer than coxa; slender P2 ischium, one and half times longer than basis, with a thin outer lateral carina; slender P2 merus, one and half times longer than ischium; slender P2 carpus, as long as ischium, with a roughly similar width all along its length; P2 propodus as long as carpus, with straight margins, tapering distally, 2/3 of it represented by the palm, the rest by the pointed manus; P2 dactylus slightly longer than manus, straight, with a very slightly curved distal portion (Fig. 2A4, A5); slender pereiopod 3 (P3, thoracopod 6), slightly longer than P2 (Fig. 2A1); short and wide P3 coxa, with setobranch and mastigobranch; subtrapezoidal P3 basis, longer than coxa; slender P3 ischium tapering slightly proximally, with a thin outer lateral carina and a row of four sharp, relatively long spines ventrally; slender P3 merus almost twice as long than ischium, with a thin outer lateral margin and a ventral row of eight spines; P3 carpus shorter than basis; slender P3 propodus, 2/3 as long as merus; P3 dactylus not preserved; pereiopod 4 (P4, thoracopod 7) slender, slightly shorter than P3 (Fig. 2A1); short and wide P4 coxa, with very small setobranch and mastigobranch; subtrapezoidal P4 basis, longer than coxa; slender P4 ischium tapering slightly proximally, with a thin outer lateral carina and a row of five sharp, relatively long spines ventrally; slender P4 merus almost twice as long than ischium, with a thin outer lateral margin and a ventral row of eight spines; P4 carpus shorter than basis; slender propodus, 2/3 as long as merus; P4 dactylus not preserved; slender pereiopod 5 (P5, thoracopod 8), distinctly shorter than P4; short and wide P5 coxa, probably without setobranch and epipod; P5 basis smaller than P4 basis; P5 ischium with a thin outer lateral carina and two spines ventrally; P5 merus subcylindrical, longer than ischium, with a row of four spines ventrally; P5 carpus short and narrower than merus; P5 propodus slender; P5 dactylus not preserved.

Pleonal appendages: Pleopods 1–5 poorly preserved with protopods four times wider than long, elongate flagella about as high as pleonites (Figs. 1A4, A5, 8A5); uropod with short and stocky basis, endopod and exopod flat, subrectangular, about three times longer than wide.

Endophragm, epimerite, and sternites (Fig. 2B3): Endophragm and sternites VI–XIII very complex in the cephalic region, defining clear arthrodial cavities for thoracopods between the endophragm sensu stricto and the sterna; cavities for P1–5 (thoracopod 3–8) in the same plane, parallel to the body axis; cavities for maxillipeds in an oblique plane relative to the body axis; sternites I–II cephalized (fused and modified); sternite III merged with mandible; sternite IV cephalized, articulated with mandibles; sternite V–VIII cephalized; epimerite incompletely preserved, most a large plate forming the inner wall of branchial chamber, gently curving outward anteriorly to meet cephalothoracic shield, straight posteriorly, crossed by two short vertical (ventro-dorsal) ridges and by three vertical (ventro-dorsal) anterior epimeral bars, all five ridges emanating from endopleurites.

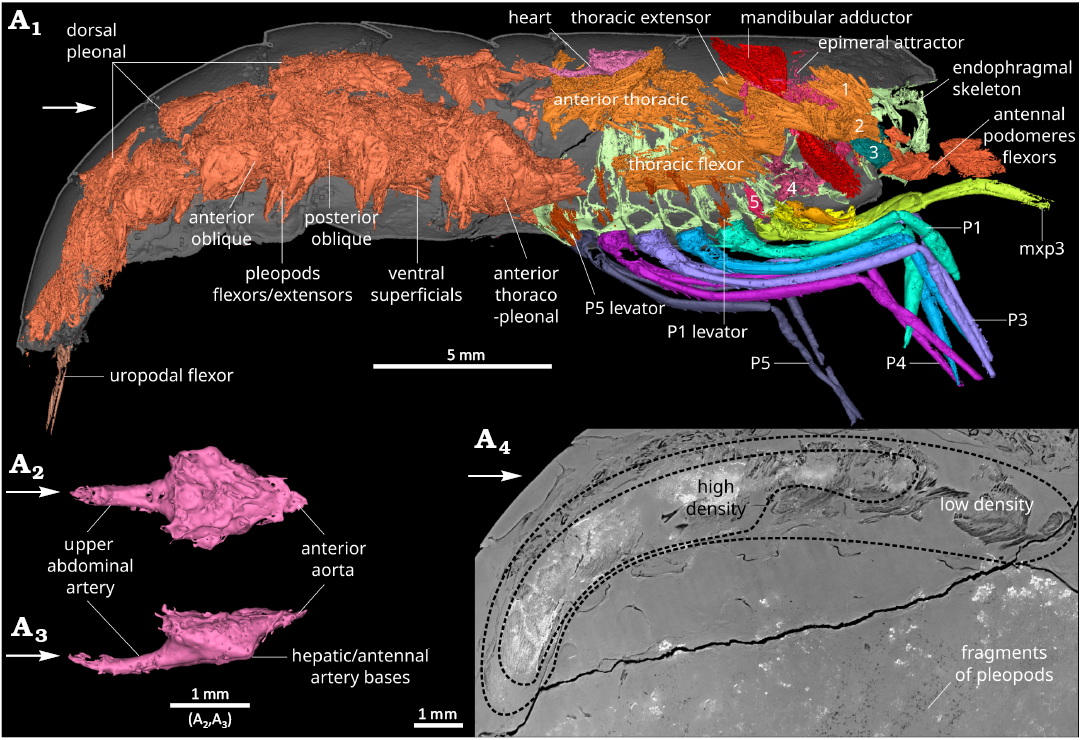

Musculature (Fig. 7): Musculature of the pleon strongly developed, occupying most of the available space (Fig. 7A1, A4); musculature also well-developed in the cephalothorax (Fig. 7A1); antennal and antennal gland muscles formed of a group of developed antennal promotor (?) muscles laying along the mesial side of antennal gland (Figs. 3A1, A2, A5, 7A1); antennal gland muscles attached to the cephalothoracic shield and endophragm laying abaxially along the antennal gland; large mandibular muscles; mandible posterior adductor muscle attached dorsally to the inside of cephalothoracic shield, surrounding the pyloric stomach, and attached ventrally to the apodeme of mandibles; mandible anterior adductor muscle filling the coxal body (Fig. 5A8) and connecting to the endophragmal compressor bundle of muscles; adductors and abductors of maxillae and maxillulae subhorizontal, connecting the appendages to the cephalothoracic shield and appendages to the endophragmal compressor; mxp1–2 adductors attached to segments VI–VIII; mxp3 and P1–5 elevators in ventral position, tightly packed against thoracic flexors; thoracic extensors attached anteriorly to the anterior portion of the cephalothoracic shield, near the insertion of antennae, spindle-shaped, oblique in lateral view, laying outside (abaxial) to the mandibular muscles, inward along epimerite; thoracic flexors ribbon-shaped, approximately aligned to sagittal plane, curving slightly inward ventrally, attached to epimerite posterior to antennae insertion; thoracic anterior muscle in dorsal position, in the posterior part of cephalothorax, connected to both cephalothorax and pleon, subdividing in two strands in the cephalothorax; anterior thoraco-abdominal muscle connection thoracic flexor to pleonal muscles; dorsal pleonal extensor muscles, including superficial and deep extensors; covering dorsally the proctodeum, attached to pleonites margins; massive ventral pleonal muscles comprising anterior and posterior oblique muscles, and transversal muscles; superficial flexor forming two thin bands lying in the ventral part of the pleon; pleopod 1–5 flexors and extensors massive, located abaxially relative to the other muscles, between the obliques and the inside of tergopleura; uropod flexor at least partially included in the uropodal basis; musculature around oesophagus and stomach connecting stomach wall (notably around ossicles, gastric mill, and pyloric valve) to each other, to the epimerites, and endophragmal skeleton.

Respiratory system: Some gills partially preserved in the branchial chamber, too poorly preserved to ascertain their type (Figs. 1A5, 2B3); presence of mastigobranch on mxp3, P1–3; presence of setobranch on P1–3.

Circulatory system: Heart subpentagonal, longer than wide, anterior part leading to the anterior aorta (Figs. 1A5, 5A1, 7A1–A3, 8A5); anterior aorta forming a short, thin, cylinder on the median axis; posterior aorta also in the median axis, connected to the heart in a more ventral position than anterior aorta; base of the antennal and hepatic artery forming two flat ridges ventrally, on either side of the heart; faint traces of an artery placed dorsally in the cephalic region.

Excretory system: Pair of antennal glands located at the junction between antenna and endophragmal skeleton; each gland with a dense network of tubules, and with a thin epithelium delimiting the ovoid (in outline in lateral view) bladder; bladder laterally surrounded by its muscles and those of the antenna.

Digestive system: Oesophagus subparallelepipedic in outline in lateral view, opening ventrally above the molar process of mandibles (Figs. 3A2, A6, A7, 5A2, A3, A9); mouth, at the ventral opening of oesophagus forming a valve; no labrum or setae visible; stomach composed of two chambers, a cardiac stomach and pyloric stomach (Figs. 5A1–A3, A5, A8, 6A1, A2); cardiac stomach (Fig. 5A1–A3, A8) placed dorsally to the oesophagus and mandibles, surrounded by the epimerite attractor muscles; no ossicle visible in the dorsal portion of the cardiac stomach; gastric mill located ventrally in the cardiac stomach, near the connexion to the pyloric stomach; ossicles of the gastric mill forming longitudinal folds (Fig. 5A3, A8, A9); urocardiac, zygocardiac, pterocardiac, pyloric, and uropyloric ossicles present; urocardiac and pyloric ossicles almost fused, forming a distinct spine posterior to the gastric mill; pair of pterocardiac ossicles located anterolaterally to the urocardiac ossicle, forming two oblique plates surrounding the pyloric tooth, in frontoventral view; uropyloric tooth forming a small ledge under pyloric tooth; cardiopyloric valve (Fig. 5A9) in continuity to the gastric mill, parallel to the longitudinal axis of the body, crossing pyloric stomach; pyloric stomach (Fig. 5A1–A3, A5) connected ventrally to the hepatopancreas atrium through the pyloric filter; pyloric stomach also connected posteriorly to the mesoteron and proctodeum; pyloric filter formed of two sets of lamellae forming (Fig. 5A1, A5–A7); posteriorly both sets of pyloric filter lamellae connecting in an inverted V-shape, anteriorly, both sets curving slightly posteriorly and tapering in width; proctodeum roughly in the shape of a cylinder, lying for the most part slightly medially and above the mid-height of pleonites (Figs. 5A1, A2, 6A1); massive hepatopancreas occupying most of the available space in the body cavity, and reaching second pleonite; formed of a pair of anterior lobes, a pair of median lobes, and a pair of posterior lobes (Fig. 5A1, A2, A4); anterior lobe of the hepatopancreas placed between the mandible and part of the endophragmal skeleton; median lobes enveloping stomach walls; posterior lobes of the hepatopancreas elongated, placed posteriorly and reaching second pleonite; hepantopancreatic lobes composed of numerous tubules giving to the tissue a spongious aspect in section; hepatopancreatic atrium (cavity underneath the pyloric filter) leading to four main collector ducts (Fig. 5A4), leading deeper into the hepatopancreas (Fig. 5A1).

Fig. 5. 3D model of digestive system of the caridean shrimp Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. Virtual slice in sagittal view of the whole specimen, with digestive tract and hepatopancreas highlighted (A1). Digestive system in right lateral view (A2) and detail of the anterior part of the digestive tract, hepatopancreas omitted (A3). Oblique dorsal view of the hepatopancreas, at the level of the atrium (A4), showing four main collecting ducts starting from the atrium. Virtual slice in axial view at the level of the pyloric filter (blue) (A5). Pyloric filter in right lateral (A6) and ventral (A7) views. Virtual slice in axial view at the level of the gastric mill (green) (A8). Gastric mil and oesophagus in dorsal view (A9). White arrows point to the front, L/ R, left/ right. Abbreviation: a1 muscles, antennula muscles; mx1, maxillula; P1–5, pereiopods 1–5.

Nervous system (Fig. 3A1, A2, A5–A7): Two anterior pairs of cephalic ganglia (proto, mesocerebrum, Fig. 3A6, A7) preserved anterior to the oesophagus, probably surrounded by neuropils; third pair not preserved; peri-oesophagial connective thick, surrounding oesophagus on either sides, suboesophagial ganglia and commissure connected to peri-oesophagial connective (Fig. 3A1, A2, A6, A7); antennal nerves forming slender thread extending toward the base of antenna from the cephalic ganglia; ventral chain and ganglia poorly preserved, visible ventrally in the cephalothorax (Fig. 3A5) and partially in the pleon.

Reproductive system: Gonopores not visible on either P3 or P5, no gonads or ducts visible, possibly as a combined consequence of the blind zone above the insertion of pereiopods and the crack at the base of pereiopods (Figs. 4A4, 5A1, A5, A7, 7A4, 8A5).

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte-sur-Rhône, Ardèche, France.

Results

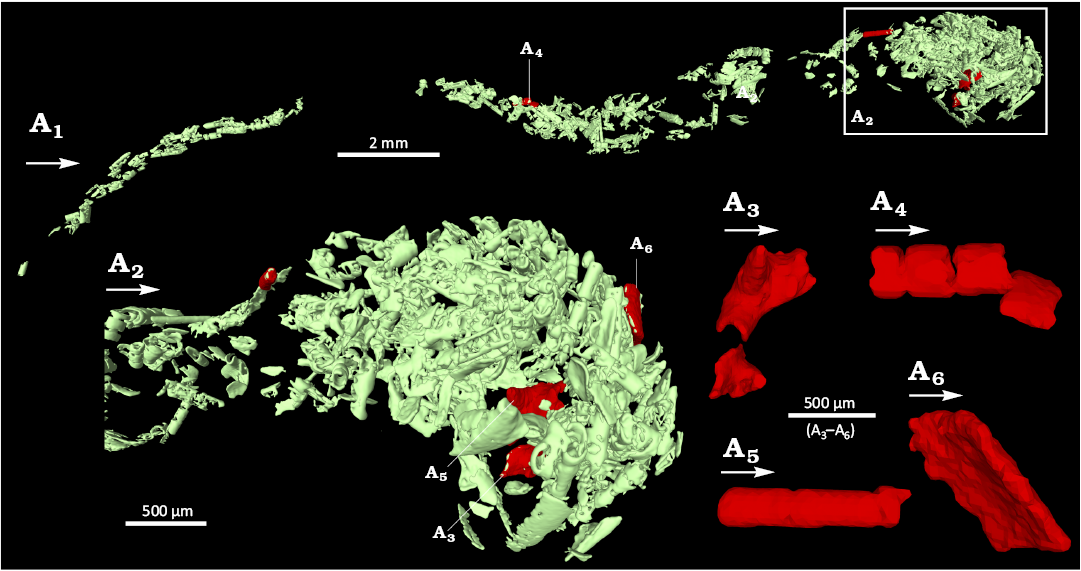

Gut content.—The cardiac stomach and proctodeum of the holotype are filled with ingested food fragments (Fig. 6). By contrast, the pyloric stomach does not contain any visible fragments. The majority of fragments resemble small tubes, often series of a few aligned, short tubes; other fragments resemble flat or slightly curved plates, some of which with spiny protuberances. The cardiac stomach contains slightly larger fragments than the proctodeum. While the fragments in the cardiac stomach appear to be randomly packed, those in the proctodeum appear to be partially aligned along its axis.

Fig. 6. Content of the digestive track of the caridean shrimp Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. Overview of the content of the whole digestive tract (A1), contents of the stomach (A2). A3–A6, highlighted fragments, interpreted as of arthropod (?) origin. White arrows point to the front.

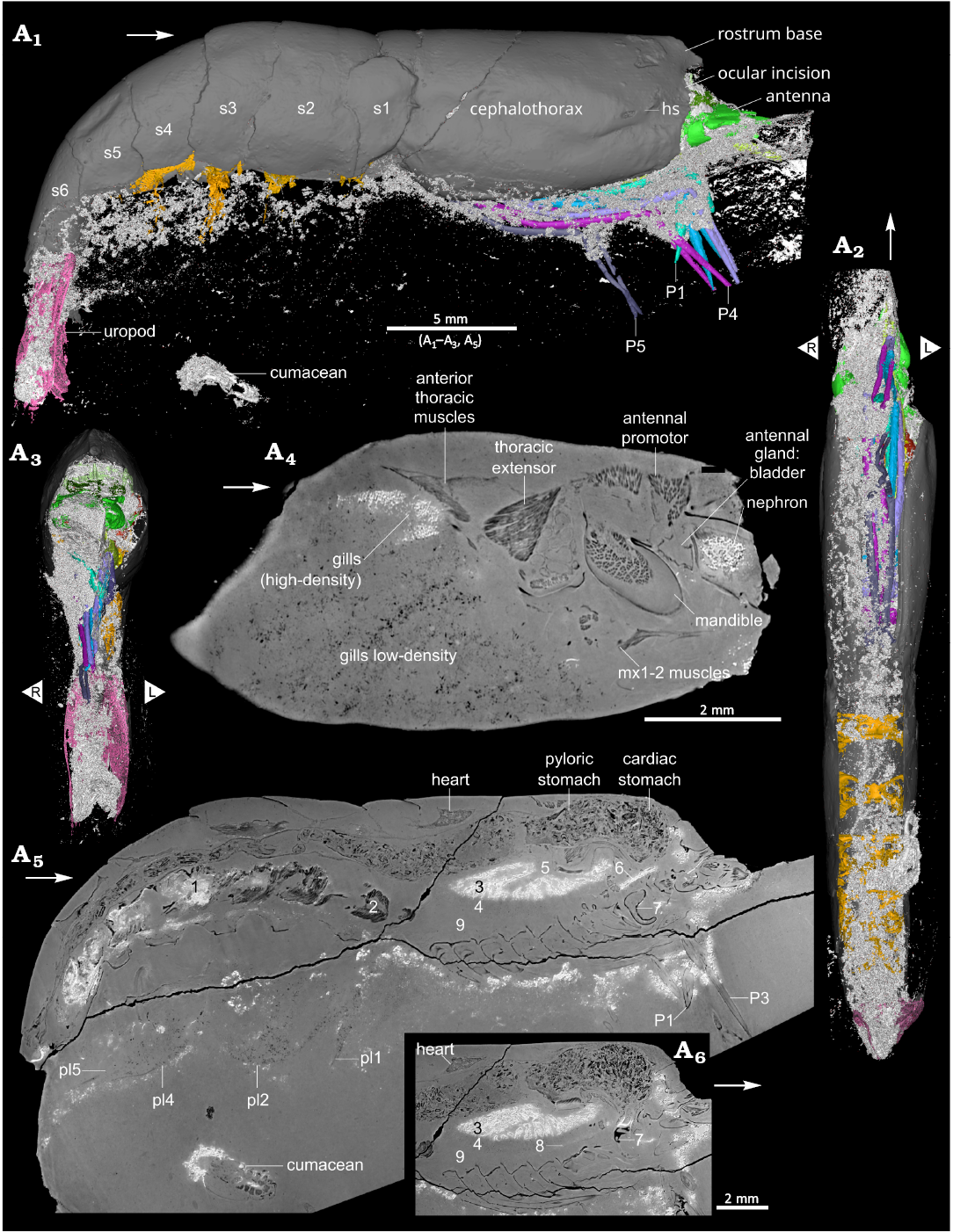

Preservation.—General aspect: The holotype of Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (as well as an indeterminate cumacean of about 2.3 mm long, Fig. 8A1–A5; not studied here) is preserved within a nodule, which was previously, partially excavated to free the specimen and allow its observation (Fig. 1). As a drawback (see also Jauvion et al. 2020a), this excavation unfortunately led to the loss of the rostrum, eyes, some cephalic appendages, tips of P1 and P2 chelae, and part of the telson. The nodule surface appears rough, it is slightly brownish, deeper parts of the matrix are dark grey. Several cracks are present across the nodule; of the two largest, one cuts the base of the pereiopods (Figs. 4A4, 5A1, A5, A8, 7A4, 8A5), thus preventing the observation of the gonopores, while the other one cuts the posterior part of cephalothorax obliquely, without preventing the observation of structures. The large cracks do not appear to have affected the preserved soft parts.

Preservation of structures: Most of the specimen is exquisitely preserved, notably the exoskeleton, digestive system (Fig. 5) including the gastric mill (Fig. 5A9), muscles (Fig. 7) and antennal glands (Fig. 4A1, A2), and even parts of the nervous system (Fig. 4A5–A7). Some structures are nevertheless lacking, incompletely or poorly preserved. Missing structures include the whole reproductive system, exopods of mouthparts (Fig. 3) and pereiopods, and some muscles. Poorly preserved structures include pleopods 1–5 (Figs. 1A4, 5A4, 8A5) and gills (Fig. 8A4). A region of the specimen is conspicuously devoid of preservation of most structures (see Fig. 8A5). This region (“blind zone”), extends from the base of the thoracopods (maxillipeds, pereiopods) to the underside of the hepatopancreas, and from the base of the maxillipeds to the first pleonal somite. It should have contained thoracopod muscles and the lowermost portion of the hepatopancreas. This area is not entirely empty as in its anterior half, traces of the ventral nerve chain are visible.

Fig. 7. Musculature of the caridean shrimp Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. Musculature, right lateral view (A1), with parts of exoskeleton and endophragm for context. Heart, dorsal (A2) and right lateral (A3) views. Sagittal slice of the pleon’s musculature (A4). Captions: antennal promotor (1), antennal remotor (2), antennal gland muscle (3), maxillula and maxillae adductor and flexor muscles (4), first pereiopod (P1) levator (5). Abbreviations: mxp3, third maxilliped; P1–5, pereiopods 1–5. White arrows point to the front.

Mineral density of preserved structures: PPC-SRµCT for the most part translates the opacity to X-rays into a greyscale in the dataset: the whitest areas in virtual slices correspond to areas in the specimen blocking more X-rays, the darkest areas in virtual slices to areas in the specimen blocking less X-rays. The greyscale is also affected by phase shift, increasing the contrast at the boundary between minerals when their refringence differs. In our specimen of Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov., fossilised structures exhibit various opacities to X-rays represented as various shades of grey (Figs. 4A4, A5, 5A1, A5, A8, 7A4, 8A4, A5), suggesting that several minerals are implied in the preservation of the body tissues. Table 1 summarizes density and texture observed for various structures, compared to the matrix. According to a previous study conducted on thylacocephalans from La Voulte (Jauvion et al. 2020b), we infer that the whitest areas of the virtual slices correspond to areas rich in iron and possibly lead, and the darkest areas to areas rich in calcium/magnesium carbonate or phosphate, such as the sediment matrix.

Table 1. Tissue densities inferred from X-ray absorption.

|

Type of tissue |

Density |

Texture |

|

Cuticle |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Endophragm and epimerite |

low, locally high |

fine and precise for low density, coarse for high density |

|

Muscles |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Pleonal muscles (dorsal) |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Pleonal muscles (ventral) |

high |

fine, precise |

|

Neural |

high |

coarse |

|

Gills |

high |

fine, precise |

|

Digestive tract epithelium |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Hepatopancreas (dorsal and posterior) |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Hepatopancreas (ventral, anterior part) |

high |

fine, precise |

|

Antennal gland (left) |

high |

coarse |

|

Antennal gland (right) |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Heart |

low |

fine, precise |

|

Oesophagus |

high |

coarse |

|

Anus |

high |

coarse |

|

Fragments in gut content |

low |

fine, precise |

Fossilised structures are replaced by at least two types of minerals of differing density (see Table 1, Figs. 4A4, 7A4, 8A4, A5). The distribution of high- and low-density minerals is complex: part of it seems driven by the tissue it replaces, for instance, the cuticle (exoskeleton, endophragm, epimerite) is mainly replaced, quite precisely, by a low-density mineral. On the other hand, there are a few examples where similar tissues can be replaced by either a high-density mineral or a low-density mineral, or sometimes concurrently. The low-density mineral(s) tends to reproduce a high-level of details in the fossilised structures. Contrastingly, the high-density mineral(s) tends to be coarser in aspect, obscuring a few of the finer morphological details. The most striking example is the pair of antennal glands (Fig. 4A4), where the left gland is coarsely replaced by high-density mineral(s), and the right one is replaced by low-density mineral(s). When a contact area exists between the two minerals, it is abrupt, without visible gradient, as clearly seen for the endophragmal/epimeral skeleton in the cephalic area and for the hepatopancreas (Fig. 8A5). For the pleonal muscles (Fig. 7A4) and hepatopancreas (Figs. 5A1, A5, 8A5), two tissues occupying a large part of the body cavity, the dorsal portion comprises more low-density mineral(s), and the ventral portion comprises more high-density minerals.

Small dense grains of minerals also occur in bundles within the matrix around the fossil (Fig 8). These bundles are mostly localised on the ventral side of the body, around the base of the pereiopods, or around the pleopods, and on the right side of the fossil (Fig. 8A1, A3). Comparisons with other fossils from La Voulte reveal that similar bundles do not occur in all fossil arthropods from La Voulte. For instance, in the female specimen of Eryma ventrosum studied by Charbonnier et al. (2024: fig. 4 and original dataset), no bundles are present outside of the body cavity. In the specimen of Willemoesiocaris ovalis studied by Audo (2014: fig. 96, and original dataset), bundles of dense mineral(s) occur as a halo parallel to the surface of the nodule. On the other hand, as in the holotype of Voulteryon parvulus (slightly visible in Jauvion et al. 2016: fig. 5F), the holotype of Palaeopolycheles nantosueltae (see online CT-data from Jauvion et al. 2020a), and a male of Eryma ventrosum (see Charbonnier et al. 2024: fig. 5I and original dataset), bundles of dense mineral grains occur mostly on the ventral surface and around the base of the appendages. It is also worth noting that in the Carboniferous Konservat-Lagerstätte of Montceau-les-Mines, several nodules yielding the syncarid shrimp Palaeocaris secretanae Schram, 1984, also display halos of pyrite, a dense mineral (Perrier et al. 2006; Perrier and Charbonnier 2014).

Fig. 8. Preservation of the caridean shrimp Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. (holotype, MNHN.F.A58277) from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of La Voulte, France. White: denser (to X-ray) mineral. 3D reconstruction of the specimen right lateral (A1), ventral (A2), and frontal (A3) views. Sagittal virtual slice of the left branchial chamber (A4), whole specimen near the median line (A5), close-up of a virtual slice in sagittal view, in a slightly different (A6) showing traces of the ventral chain of the nervous system. Captions: muscles preserved in dense (1) and light (2) mineral; hepatopancreas preserved in dense (3) and light (4) mineral; hepatopancreas atrium (5); nerve chord in dense mineral (6); mandible (7); faint remains of ventral chain (8); “blind zone”, devoid of preserved structures (9). Abbreviations: hs, hepatic spine; mx1, maxillulae; mx2, maxillae; P1–5, pereiopods 1–5; pl1–5, pleopods 1–5; s1–6, pleonites 1–6. White arrows point to the front. L/R, left/right.

Discussion

Palaeoecology.—Recent Acanthephyridae are mesopelagic shrimps living between 200 and 4000 meters and benthic between 1000 and 4000 meters (Omori 1974; Chace 1986; Poore and Ahyong 2023). In this context, it appears La Voulte-sur-Rhône palaeoenvironment was at the shallow end of present-day acanthephyrid depth distribution. The morphology of Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. suggests it was pelagic: its elongated sixth pleonite, pleopods, uropods, and its massive pleonal muscles all are characteristics tied to swimming potential in extant species (Bauer 2004; Boudrias 2013); in addition, its pereiopods are shaped in a way so that they can be packed tightly together, thus reducing the drag.

The cardiac stomach and proctodeum of M. polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. are filled with many fragments resembling gently curved plates and series of cylinders (Fig. 6). These are interpreted as fragments of axial exoskeleton (e.g., tergites and sternites) and fragments of multiarticulated appendages such as antennae and exopods, respectively. This strongly suggests M. polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. was feeding mainly on arthropods, unfortunately unidentifiable due to the small size of the fragments. Studies based on gut-contents from extant Acanthephyridae (Foxton and Roe 1974; Cartes 1993; Burukovsky and Falkenhaug 2015) suggest they are mostly predatory, feeding on actinopterygian fishes, decapods, and copepods. The absence of remains of large animals and plants or slow-moving preys such as echinoderms and gastropods is not consistent with an opportunistic to mostly necrophagous diet. More precisely, the abundance of multiarticulated elements may correspond to arthropods with long antennae and exopods, so it is likely that the diet of M. polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. was mostly based upon planktic arthropods. This gut content and the morphology of M. polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. lead us to infer this species swam in the water column to hunt its prey.

Taphonomy.—Mineralogical distribution: We did not perform any chemical analysis on the specimen to avoid destructive sampling of the internal anatomy. Thus, because carbonate and phosphate for instance have a similar response to X-rays, it is hard to attribute precisely the minerals in presence. However, former studies realised on decapod crustaceans and thylacocephalans from La Voulte have identified phosphate ([fluoro]apatite), carbonates (magnesian or ferroan calcite, dolomite), sulfides ([chalco]pyrite; wurtzite; galena; pyrrhotite) and clays, as well as sulfates and iron oxides after oxidation (Wilby et al. 1996; Jauvion et al. 2020b). It is thus reasonable to ascribe the denser mineral(s) to sulfide(s) and the low-density ones to carbonate and/or phosphate. Critically, in the specimen studied here there seems to be a spatial gradient whereby the preservation follows a ventro-dorsal path. Indeed, the ventral part seems to have the poorest preservation while the dorsal part is better preserved (Figs. 5A1, 8A4, A5); the mostly empty area (“blind zone”, Fig. 8A5), located on the ventral part of the cephalothorax, should have for instance contained pereiopod muscles, while muscles are well-preserved elsewhere; the hepatopancreas is well-preserved in the dorsal part but degraded in the ventral part (Figs. 5A1, 8A5, A6); the nervous system is relatively well-preserved around the oesophagus (Fig. 4A2, A6, A7), but the ventral nerve cord is only faintly visible anteriorly (Fig. 8A6), ending in the mostly empty area above the pereiopods; while most of the gills are degraded, fragments are preserved at the top of the branchial chamber. This is paralleled by the mineralogical spatial distribution: the dorsal part is preserved in low-density mineral(s) with acute details (heart, most of the hepatopancreas tubules and the right-side antennal gland) while the ventral part, comprising the nervous system, ventral pleonal muscles and part of the hepatopancreas, and left antennal gland, are preserved by denser mineral(s). The latter allowed a detailed but coarser preservation of organs.

In parallel to this general trend of mineralization, several controls may have influenced the spatial distribution of minerals. Fossil evidence and experimental data emphasise that taxa and composition of tissues influence arthropod fossilization (Plotnick et al. 1988; Briggs and Kear 1994; Wilby et al. 1996; Klompmaker et al. 2017). For instance, on soft tissues preserved in La Voulte, Wilby et al. (1996: 848) noted that apatite was “restricted largely to muscle tissues”. This does not fit the observations made on the present specimen, as most of the cuticle, hepatopancreas, and one of the antennal glands are most likely preserved in apatite, and conversely, some muscles are replaced by dense mineral(s). In the specimen, the nervous tissues are preserved by a dense mineral that we attribute as being (chalco)pyrite. Such association between iron (from pyrite or oxides after pyrite) and nervous tissues was already noted (Janssen et al. 2022), including in other fossil arthropods, such as from the Cambrian Chengjiang Biota (Tanaka et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2015). This may be due to a biogenic origin of iron, delivered by the nervous system during decay, thus favouring preservation of nervous tissues by precipitation of pyrite (Saleh et al. 2020). However, the high-density mineral(s) also preserved features of M. polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. directly in contact with the exterior (anus, oesophagus). Such observation would turn the origin of iron towards an external contribution, which is in line with geochemical evidence of La Voulte water being rich in metals, including iron, due to a hydrothermal environment (Wilby et al 1996; Charbonnier 2009). Finally, the preservation of the left antennal gland in a high-density mineral and the right antennal gland in low-density mineral evidence that micro environmental variations (here at a scale of two millimetres) have a huge influence on the minerals preserving organic structures.

Taphonomical scenario.—Based upon the changes in density across the tissue of the fossil Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. described here, we suggest the following scenario of preservation:

First phase—life, death and deposition: We assume that the shrimp lived in La Voulte or its close vicinity, most likely in the water column, possibly returning near the bottom to rest, according to its morphology and gut-content. Once dead, possibly after poisoning from hydrothermal vent activity, its carcass fell on the water/sediment interface and was deposited on the sediment on its right side, as suggested by (i) the alignment of the pereiopods and (ii) a higher abundance of dense mineral in the sediment on such side of the nodule. Indeed, in sediment columns, the zone producing sulfides is located below the zones where phosphatization and calcification occurred (Muscente et al. 2023), evidencing that the right part of the nodule was facing downwards.

Second phase—burial, early decay and mineralization: The carcass was rapidly covered, by finely laminated sediments or microbial films, preventing it from damage due to scavenging, as the specimen does not exhibit traces of them. Quickly entombed in the anoxic zone of the sediment column, the carcass underwent microbial activities, leading to the precipitation of phosphates, such as fluorapatite (seen as low-density areas in the tomographic data). Sulfides (seen as high-density areas in the tomographic data) precipitated concomitantly, as hypothesised by Jauvion et al. (2020b) who identified both minerals within the same organic structures, or later (Wilby et al. 1996), because of the carcass sinking deeper into the sediment column, towards the microbial sulfate-reducing zone. Meanwhile, both internal and external sources of iron aided in the mineralization of structures, leading to the pyritization of particular internal organs (nervous system) and organs open to the exterior (anus, oesophagus). Finally, fluids rich in heavy ions (copper, zinc, lead, iron, etc.), deriving from La Voulte’s hydrothermal activity (Wilby et al. 1996; Charbonnier 2009), penetrated the carcass through the ventral side of the shrimp, where the porosity of the carcass was greater due to the many arthrodial membranes, more numerous on the ventral side than on the dorsal one. This led to the preservation in a high-density mineral(s) of ventral organs such as some pleonal muscles, part of the hepatopancreas, brain, and one antennal gland. Because they were close to the outside, the oesophagus, terminal part of hindgut and anus are also preserved in high-density mineral(s). The gills are another interesting example: they are mostly reduced to low-density fragments, except in the upper part of branchial chamber, opposite the branchial chamber opening. In contrast, the excretory pore (nephropore), the outlet of the antennal gland does not seem to be linked to a higher concentration of dense minerals. Thus, in general, a high exposure to the outside led to the high-density mineral formation in the upper branchial chamber. In the lower branchial chamber, the exposure was so high that it led to a higher decomposition during the third phase.

Third phase—decay microenvironment opening: With progressing decay, disarticulation and loss of integrity happened, notably between the cephalothorax and pleon. According to Klompmaker et al. (2017), these structural alterations happen within about 50 days. Fluids and sediments flowing in the ventral side of the carcass then invaded parts of the decaying carcass obliterating organs, such as pereiopod muscles in the cephalothorax, part of the hepatopancreas, a small portion of the muscles of the pleon, most of the gills, pereiopod exopodites, pleopods, and most likely parts of the reproductive tracts and gonads. The most noticeable internal sediment flux concerns the ventral portion of the body cavity between the cephalothorax and the pleon, which led to a ventro-dorsal spatial gradient of preservation. This sediment influx was most likely favored by the relative fragility of the tegument connecting the cephalothorax to the pleon (Allison 1986, 1988; Plotnick 1986). Further, this influx may have partially oxidised the pyrite formed earlier (Jauvion et al. 2020b), enhancing the degradation of the preservation quality.

Fourth phase—cementation and nodule formation: The opening of the micro-environment and increase in pH (Jauvion et al. 2020b) finally led to the cementation of spaces between mineralised structures, and around the carcass in magnesian calcite. Here, the nodule forming around the shrimp also encompassed a small crustacean (cumacean). This was also noted in the nodules of the holotype of Palaeopolycheles nantosueltae Jauvion et al., 2020a, and of the holotype of Hellerocaris falloti (Van Straelen, 1923), both also encompassing an ophiuroid each, showing that multiple organisms in a nodule is not an isolated event.

Fifth phase—diagenesis: After full lithification, (septarian?) fractures developed within the nodule, without perturbing the preservation of the specimen (no mineralogical differences are visible on both sides of the fractures). No discernible compaction of the nodule happened, contrary to numerous larger nodules bearing large polychelidans (see Audo et al. 2014: figs. 3, 4, 6A–C, 10). After discovery of the fossil, mechanical preparation led to the loss of protruding structures, such as rostrum, tips of chelae, and telson.

Conclusions

The holotype of Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et sp. nov. increases our knowledge of the arthropod diversity at La Voulte, in this case with a shrimp that may have lived in the water column above the seafloor. Mandocaris polyphaga gen. et. sp. nov. is currently the only known occurrence of an Acanthephyridae in the fossil record. As such, it may help better understand the evolution of oplophorids and caridean shrimps in general. Synchrotron imaging was instrumental in identifying this species. Indeed, a poor historic preparation had destroyed the rostrum, an important source of diagnostic characters. In addition to the purely palaeobiological aspects of this dataset, synchrotron imaging is also an invaluable tool to better understand the taphonomy in La Voulte, allowing us to compare non-destructively unique specimens. More could probably be learned, and our current hypotheses could be tested with new material from La Voulte: complete, unopened nodules would allow studying the distribution of bundle of dense mineral grains in the whole nodule, notably near the dorsal surface, which is usually prepared; more specimens of the same species could allow us to better understand how taphonomy is influenced by the nature of remains being fossilized: is the species the most influential parameter for preservation, or is it something else, such as the size of the specimen or how much decay has progressed; finally, newly collected nodules with indication of their polarity relative to marl layers would allow to better understand the influence of gravity and sedimentation on the distribution of bundles of dense minerals.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities under proposal number es1298 and we would like to thank the beamline staff for assistance and support in using beamline BM18. We thank Camille Berruyer (ESRF) for help with sample mounting in preparation of data acquisition at the ESRF. We are grateful to Paula Martin-Lefèvre, Sébastien Soubzmaigne, and Laure Corbari (all MNHN) for access to extant carideans for comparisons. We acknowledge the precious contribution of Nathalie Poulet and Florent Goussard (both MNHN) who helped during the 3D reconstruction process. We thank our reviewers Matúš Hyžný (Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia) and Guenter Schweigert (Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany) for their constructive comments on an earlier version of the paper.

Editor: Andrzej Kaim

References

Allison, P.A. 1986. Soft-bodied animals in the fossil record: the role of decay in fragmentation during transport. Geology 14: 979–981. Crossref

Allison, P.A. 1988. The role of anoxia in the decay and mineralization of proteinaceous macro-fossils. Paleobiology 14: 139–154. Crossref

Audo, D. 2014. Les Polychelida, un groupe de crustacés énigmatiques. Systématique, histoire évolutive, paléoécologie et paléoenvironnements. 299 pp. Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris.

Audo, D., Dollman, K., and Fernandez, V. 2025. Synchrotron X-ray Micro Computed Tomography of a Fossil Caridean Shrimp MNHN.F.A58277 from the La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte (ca. 165 Ma) (Version 1) [Dataset]. European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, doi.org/10.15151/ESRF-DC-2183326285.

Audo, D., Robin, N., Luque, J., Krobicki, M., Haug, J.T., Haug, C., Jauvion, C., and Charbonnier, S. 2019. Palaeoecology of Voulteryon parvulus (Eucrustacea, Polychelida) from the Middle Jurassic of La Voulte-sur-Rhône Fossil-Lagerstätte (France). Scientific Reports 9 (1): 5332. Crossref

Audo, D., Schweigert, G., Saint Martin, J.-P., and Charbonnier, S. 2014. High biodiversity in Polychelida crustaceans from the Jurassic La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte. Geodiversitas 36: 489–525. Crossref

Bauer, R.R. 2004. Remarkable Shrimps—Adaptations and Natural History of the Carideans. xvii + 282 pp. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Benoit, J., Ruf, I., Miyamae, J.A., Fernandez, V., Rodrigues, P.G., and Rubidge, B.S. 2020. The evolution of the maxillary canal in Probainognathia (Cynodontia, Synapsida): reassessment of the homology of the infraorbital foramen in mammalian ancestors. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 27: 329–348. Crossref

Bishop, G.A. 1986. Taphonomy of the North American decapods. Journal of Crustacean Biology 6: 326–355. Crossref

Boudrias, M.A. 2013. Swimming fast and furious. In: Watling, L. and Thiel, M. (eds.), Functional Morphology and Diversity, 319–336. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Crossref

Bracken, H.D., De Grave, S., and Felder, D.L. 2009. Phylogeny of the infraorder Caridea based on mitochondrial and nuclear genes (Crustacea: Decapoda). In: J. Martin, K. Crandall, and D.L. Felder (eds.), Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics, 281–305. CRC Press, Bocan Raton. Crossref

Briggs, D.E.G. and Kear, A.J. 1994. Decay and mineralization of shrimps. Palaios 9: 431–456. Crossref

Brünnich, M.T. 1772. Zoologiæ Fundamenta Prælectionibus Academicis Acommodata. 253 pp. Frider. Christ. Pelt, Lipsiae. Crossref

Burkenroad, M.D. 1963. The evolution of the Eucarida, (Crustacea, Eumalacostraca), in relation to the fossil record. Tulane Studies in Geology 2 (1): 1–17.

Burukovsky, R.N. and Falkenhaug, T. 2015. Feeding of the pelagic shrimp Acanthephyra pelagica (Risso, 1816) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Oplophoridae) in the northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge area in 1984 and 2004. Arthropoda Selecta 24 (3): 303–316. Crossref

Calman, W.T. 1904. On the classification of the crustacea malacostraca. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History (Seventh Series) 13 (74): 144–157. Crossref

Cartes, J.E. 1993. Feeding habits of oplophorid shrimps in the deep western Mediterranean. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 73: 193–206. Crossref

Cau, A., Beyrand, V., Voeten, D.F.A.E., Fernandez, V., Tafforeau, P., Stein, K., Barsbold, R., Tsogtbaatar, K., Currie, P.J., and Godefroit, P. 2017. Synchrotron scanning reveals amphibious ecomorphology in a new clade of bird-like dinosaurs. Nature 552: 395–399. Crossref

Chace, F.A., Jr. 1986. The Caridean shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda) of the Albatross Philippine Expedition, 1907–1910, Part 4: Families Oplophoridae and Nematocarcinidae. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 432: 1–82. Crossref

Chace, F.A., Jr. 1992. On the classification of the Caridea (Decapoda). Crustaceana 63: 70–80. Crossref

Chan, T.-Y., Lei, H.C., Li, C.P., and Chu, K.H. 2010. Phylogenetic analysis using rDNA reveals polyphyly of Oplophoridae (Decapoda:Caridea). Invertebrate Systematics 24: 172–181. Crossref

Charbonnier, S. 2009. Le Lagerstätte de La Voulte, un environnement bathyal au Jurassique. Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle 199: 1–271.

Charbonnier, S., Audo, D., Caze, B., and Biot, V. 2014. The La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte (Middle Jurassic, France). Comptes Rendus Palevol 13: 369–381. Crossref

Charbonnier, S., Vannier, J., Gaillard, C., Bourseau, J.-P., and Hantzpergue, P. 2007. The La Voulte Lagerstätte (Callovian): Evidence for a deep water setting from sponge and crinoid communities. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 250: 216–236. Crossref

Charbonnier, S., Vogt, G., Forel, M.-B., Hieu, N., Devillez, J., Laville, T., Poulet-Crovisier, N., King, A., and Briggs, D.E.G. 2024. The La Voulte-sur-Rhône Konservat-Lagerstätte reveals the male and female internal anatomy of the Middle Jurassic clawed lobster Eryma ventrosum. Scientific Reports 14 (1): 17744 Crossref

Cignoni, P., Callieri, M., Corsini, M., Dellepiane, M., Ganovelli, F., and Ranzuglia, G. 2008. MeshLab: an Open-Source Mesh Processing Tool. Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference: 8 pp. [available online, https://doi.org/10.2312/LocalChapterEvents/ItalChap/ItalianChapConf2008/129-136].

Dana, J.D. 1852a. Conspectus Crustaceorum, &c. conspectus of the Crustacea of the exploring expendition under Capt. C. Wilkes, U.S.N. Macroura. Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of Philadelphia 6: 10–28.

Dana, J.D. 1852b. Crustacea. Part I. United States Exploring Expedition. During the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Under the command of Charles Wilkes, U.S.N. 13: 1–685.

De Grave, S. and Fransen, C.H.J.M. 2011. Carideorum catalogus: the recent species of the dendrobranchiate, stenopodidean, procarididean and caridean shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda). Zoologische Mededelingen 85 (9): 195–588.

Elmi, S. 1967. Le Lias supérieur et le Jurassique moyen de l’Ardèche. Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de la Faculté des Sciences de Lyon 1–3: 1–845.

Felgenhauer, B.E. and Abele, L.G. 1983. Phylogenetic relationships among shrimp-like decapods. In: F.R. Schram (ed.), Crustacean Phylogeny, 291–311. A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam.

Fournet, J. 1843. Études sur le terrain jurassique et les minerais de fer de l’Ardèche. Annales de la Société d’Agriculture, des Sciences de Lyon 6: 1–35.

Foxton, P. and Roe, H.S.J. 1974. Observations on the nocturnal feeding of some mesopelagic decapod Crustacea. Marine Biology 28: 37–49. Crossref

Gevrey, M.A. 1899. Note sur un gisement de crustacés fossiles découvert à La Voulte (Ardèche). Bulletin de la Société de Statistique des Sciences naturelles et des Arts industriels 4me série 4: 39–40.

Gravenhorst, J.L.C. 1843. Vergleichende Zoologie. xx + 686 pp. Graß, Barth and Comp., Breslau. Crossref

Holthuis, L.B. 1993. The Recent Genera of the Caridean and Stenopodidean Shrimps (Crustacea, Decapoda): with an Appendix on the Order Amphionidacea. 328 pp. Nationaal Natuurhistorisch. Museum, Leiden. Crossref

Hyžný, M. and Klompmaker, A. 2015. Systematics, phylogeny, and taphonomy of ghost shrimps (Decapoda): a perspective from the fossil record. Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 73: 401–437. Crossref

Hyžný, M., Kroh, A., Ziegler, A., Anker, A., Košťák, M., Schlögl, J., Culka, A., Jagt, J.W.M., Fraaije, R.H.B., Harzhauser, M., Van Bakel, B.W.M., and Ruman, A. 2017. Comprehensive analysis and reinterpretation of Cenozoic mesofossils reveals ancient origin of the snapping claw of alpheid shrimps. Scientific Reports 7: 4076. Crossref

Janssen, K., Mähler, B., Rust, J., Bierbaum, G., and McCoy, V.E. 2022. The complex role of microbial metabolic activity in fossilization. Biological Reviews 97: 449–465. Crossref

Jauvion, C., Audo, D., Bernard, S., Vannier, J., Daley, A.C., and Charbonnier, S. 2020a. A new polychelidan lobster preserved with its eggs in a 165 Ma nodule. Scientific Reports 10 (1): 3574. Crossref

Jauvion, C., Audo, D., Charbonnier, S., and Vannier, J. 2016. Virtual dissection and lifestyle of a 165-million-year-old female polychelidan lobster. Arthropod Structure & Development 45 (2): 122–132. Crossref

Jauvion, C., Bernard, S., Gueriau, P., Mocuta, C., Pont, S., Benzerara, K., and Charbonnier, S. 2020b. Exceptional preservation requires fast biodegradation: thylacocephalan specimens from La Voulte‐sur‐Rhône (Callovian, Jurassic, France). Palaeontology 63: 395–413. Crossref

Klompmaker, A.A., Hyžný, M., Portell, R.W., Jauvion, C., Charbonnier, S., Fussell, S.S., Klier, A.T., Tejera, R., and Jakobsen, S.L. 2019. Muscles and muscle scars in fossil malacostracan crustaceans. Earth-Science Reviews 194: 306–326. Crossref

Klompmaker, A., Kloess, P., Jauvion, C., Brezina, J., and Landman, N. 2023. Internal anatomy of a brachyuran crab from a Late Cretaceous methane seep and an overview of internal soft tissues in fossil decapod crustaceans. Palaeontologia Electronica 26: a44. Crossref

Klompmaker, A.A., Portell, R.W., and Frick, M.G. 2017. Comparative experimental taphonomy of eight marine arthropods indicates distinct differences in preservation potential. Palaeontology 60: 773–794. Crossref

Krause, R.A., Parsons-Hubbard, K., and Walker, S.E. 2011. Experimental taphonomy of a decapod crustacean: Long-term data and their implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 312: 350–362. Crossref

Latreille, P.A. 1802. Histoire naturelle générale et particulière des crustacés et des insectes. Vol. 3. 468 pp. F. Dufart, Paris. Crossref

Lunina, A., Kulagin, D., and Vereshchaka, A. 2024. The taxonomic status of Hymenodora (Crustacea: Oplophoroidea): morphological and molecular analyses suggest a new family and an undescribed diversity deep in the sea. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 200: 336–351. Crossref

Lyckegaard, A., Johnson, G., and Tafforeau, P. 2011. Correction of ring artifacts in X-ray tomographic images. International Journal of Tomography & Statistics 18 (F11): 1–9.

Ma, X., Edgecombe, G.D., Hou, X., Goral, T., and Strausfeld, N.J. 2015. Preservational pathways of corresponding brains of a Cambrian euarthropod. Current Biology 25: 2969–2975. Crossref

Martin, J.W. and Davies, G.E. 2001. A updated classification of the Recent Crustacea. Science Series of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles 39: i–v, 1–124.

Mazancourt, V., de, Wappler, T., and Wedmann, S. 2022. Exceptional preservation of internal organs in a new fossil species of freshwater shrimp (Caridea: Palaemonoidea) from the Eocene of Messel (Germany). Scientific Reports 12 (1): 18114. Crossref

Meyer, H. von 1835. Briefliche Mittheilungen. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefactenkunde 1835: 328–329.

Mirone, A., Brun, E., Gouillart, E., Tafforeau, P., and Kieffer, J. 2014. The PyHST2 hybrid distributed code for high speed tomographic reconstruction with iterative reconstruction and a priori knowledge capabilities. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 324: 41–48. Crossref

Münster, G., Graf zu, 1839. Decapoda Macroura – Abbildung und Beschreibung der fossilen langschwänzigen Krebse in den Kalkschiefern von Bayern. Beiträge zur Petrefacten-Kunde 1839 (2): 1–88.

Muscente, A.D., Vinnes, O., Sinha, S., Schiffbauer, J.D., Maxwell, E.E., Schweigert, G., and Martindale, R.C. 2023. What role does anoxia play in exceptional fossil preservation? Lessons from the taphonomy of the Posidonia Shale (Germany). Earth-Science Reviews 238: 104323. Crossref

Omori, M. 1974. The biology of pelagic shrimps in the ocean. Advances in Marine Biology 12: 233–324. Crossref

Paganin, D., Mayo, S.C., Gureyev, T.E., Miller, P.R., and Wilkins, S.W. 2002. Simultaneous phase and amplitude extraction from a single defocused image of a homogeneous object. Journal of Microscopy 206: 33–40. Crossref

Perrier, V. and Charbonnier, S. 2014. The Montceau-les-Mines Lagerstätte (Late Carboniferous, France). Comptes Rendus Palevol 13: 353–367. Crossref

Perrier, V., Vannier, J., Racheboeuf, P.R., Charbonnier, S., Chabard, D., and Sotty, D. 2006. Syncarid crustaceans from the Montceau Lagerstätte (Upper Carboniferous; France). Palaeontology 49: 647–672. Crossref

Plotnick, R.E. 1986. Taphonomy of a modern shrimp: implications for the arthropod fossil record. Palaios 1: 286–293. Crossref

Plotnick, R.E. and McCarroll, S. 2023. Variation and taphonomic implications of composition in modern and fossil malacostracan cuticles (Decapoda: Malacostraca). Journal of Crustacean Biology 43: ruad047. Crossref

Plotnick, R.E., Baumiller, T., and Wetmore, K.L. 1988. Fossilization potential of the mud crab, Panopeus (brachyura: Xanthidae) and temporal variability in crustacean taphonomy. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 63: 27–43. Crossref

Poore, G. and Ahyong, S. 2023. Marine Decapod Crustacea: A Guide to Families and Genera of the World. 916. pp. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton South. Crossref

Rayner, M.D. 1965. A reinvestigation of the segmentation of the crayfish abdomen and thorax, based on a study of the deep flexor muscles and their relation to the skeleton and innervation. I. The skeleton and intersegmental membranes. Journal of Morphology 116: 389–412. Crossref

Saleh, F., Daley, A.C., Lefebvre, B., Pittet, B., and Perrillat, J.P. 2020. Biogenic iron preserves structures during fossilization: a hypothesis: iron from decaying tissues may stabilize their morphology in the fossil record. BioEssays 42 (6): 1900243. Crossref

Secrétan-Rey, S. 2002. Monographie du squelette axial de Nephrops norvegicus (Linné, 1758). Zoosystema 24: 81–176.

Schmidt, W. 1915. Die Muskulatur von Astacus fluviatilis (Potamobius astacus L.). Ein Beitrage zur Morphologie der Decapoden. Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie 113 (2): 165–251.

Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., Schmid, B., Tinevez, J.-Y., White, D.J., Hartenstein, V., Eliceiri, K., Tomancak, P., and Cardona, A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 9: 676–682. Crossref

Schram, F.R. 1984. Fossil Syncarida. Transactions of the San Diego Society of Natural History 20 (13): 189–246. Crossref

Schweitzer, C.E., Feldmann, R.M., Garassino, A., Karasawa, H., and Schweigert, G. 2010. Systematic list of fossil decapod crustacean species. Crustaceana Monographs 10: i–vii, 1–221. Crossref