A new giant nektobenthic radiodont benthivore from the Early Ordovician Fezouata Biota in Morocco

GAËTAN J.-M. POTIN, PÉNÉLOPE CLAISSE, ALEXIS TRÉBAOL, PIERRE GUERIAU, YU WU, STEPHEN PATES, and ALLISON C. DALEY

Potin, G.J.-M. Claisse, P., Trébaol, A., Gueriau, P. Wu, Y., Pates, S., and Daley, A.C. 2025. A new giant nektobenthic radiodont benthivore from the Early Ordovician Fezouata Biota in Morocco. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 70 (4): 709–722.

The Fezouata Shale Formation is an Early Ordovician Lagerstätte that preserved exceptionally detailed records of complex marine ecosystems, making it crucial for understanding the early evolution of animal life. It has yielded the youngest known community of radiodonts to date. This group is particularly well known from the Cambrian, with iconic representatives such as Anomalocaris, which are emblematic of the Cambrian explosion. Here we describe a new radiodont from the Fezouata Biota, Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. based on seven specimens of isolated frontal appendages. These appendages bear long endites with large and robust auxiliary spines, suggesting they were adapted for foraging through sediment in search of prey. The appendages of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. can be relatively large compared to the majority of radiodont appendages, with endites reaching up to 11.4 cm in length, suggesting a total body size exceeding one meter for this Ordovician radiodont. In contrast, smaller specimens can be up to 10 times smaller, indicating ontogenetic stages during which the frontal appendage morphology changes little. Following the “Ordovician Plankton Revolution”, the proliferation of planktonic resources and enhanced pelagic-benthic coupling during this period likely allowed for the rise of giant suspension-feeding radiodonts, such as the Aegirocassisinae and F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., the new giant benthivore. In term of taxonomic diversity, benthivores radiodonts remain a minor component of radiodont diversity in the Fezouata Biota compared to the more dominant suspension feeders.

Key words: Panarthropoda, Radiodonta, Hurdiidae, gigantism, benthivores, feeding evolution, Fezouata Shale, Early Ordovician.

Gaëtan J.-M. Potin [gaetan.jm.potin@outlook.fr; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1004-3727 ], Pénélope Claisse [penelope.claisse@hotmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6932-2938 ], Pierre Gueriau [pierre.gueriau@unil.ch; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7529-3456 ], and Allison C. Daley [allison.daley@unil.ch; ORCID: https:// orcid.org/0000-0001-5369-5879 ] Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Alexis Trébaol [alexis.trebaol6@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-1122-4259 ], 3 rue de Béniguet, 29860, Bourg-Blanc, France.

Yu Wu [yuwu92@nwu.edu.cn; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4580-4083 ], Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; State Key Laboratory of Continental Evolution and Early Life (SKLCEE), Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Early Life and Environments (SKLELE), Department of Geology, Northwest University, Xi’an, China.

Stephen Pates [s.pates@ucl.ac.uk; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8063-9469 ], Centre for Life’s Origins and Evolution, Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London; Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK.

Received 4 August 2025, accepted 17 October 2025, published online 1 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 G.J.-M. Potin et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Gigantism in the fossil record gets a lot of attention, as is the case with massive vertebrates for example (Friedman et al. 2010; Klug et al. 2015). Giant animals often represent the top-level consumers in the food webs, because they need more resources to maintain their metabolism (Moore et al. 2003; Pimiento et al. 2019; Savoca et al. 2021). Nowadays, the most iconic marine giants are suspension-feeders such as whales or whale-sharks, but some other massive animals are benthivores such as walruses (Levermann et al. 2003; Jay et al. 2014; Grebmeier et al. 2015; Moore and Stabeno 2015; Smith et al. 2015; Savoca et al. 2021). In the fossil record as well, numerous giant suspension-feeders existed, such as rays, sharks or pachycormid fishes (Friedman et al. 2010; Pimiento et al. 2019). As far as giant marine invertebrates are concerned, they were more common in the Paleozoic, with cephalopods, trilobites and sea scorpions (Perrier et al. 2015; Klug et al. 2015, 2025; Bicknell et al. 2022; Lamsdell 2025), than in the modern oceans, even though nowadays we have the giant squid Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857, that can reach a total body length of up to 18 meters (Kubodera and Mori 2005). Some giant orthoconic cephalopods in the Paleozoic could be interpreted as suspension-feeders (Mironenko 2020). In the Lower Ordovician of Morocco, the Fezouata Shale Formation yielded giant animals described as suspension-feeding radiodonts, a group of arthropods emblematic of the Cambrian explosion, and giant trilobites (Vidal 1998b; Van Roy and Briggs 2011; Van Roy et al. 2015b; Saleh et al. 2021; Potin et al. 2023; Potin and Daley 2023).

The Fezouata Shale Formation shows a quite complete snapshot of a what polar ecosystems looked like during the Early Ordovician as it yields diverse assemblages of marine animals preserved with soft tissues (Van Roy et al. 2010, 2015a; Saleh et al. 2018, 2024b; Pérez-Peris et al. 2021b; Richards et al. 2024; Lustri et al. 2024). One of the emblematic animals of the Fezouata Biota is the radiodont Aegirocassis benmoulai Van Roy et al., 2015b, a giant suspension-feeder of two meters in length, which makes it one of the largest known animals of that time (Van Roy and Briggs 2011; Van Roy et al. 2015b; Potin et al. 2023). Radiodonts occur from the early Cambrian to the Early Ordovician (with one possible specimen in the Devonian, Kühl et al. 2009), and they are considered to be predators, either nektonic or nekton-benthic, or suspension-feeding (Van Roy et al. 2015b; Daley and Legg 2015; Daley et al. 2018; Guo et al. 2019; Edgecombe 2020; Potin et al. 2023; Potin and Daley 2023).

The best known radiodont body parts are the frontal appendages, because their sclerotized nature lends them the highest preservation potential. Radiodont frontal appendages are therefore crucial in interpreting taxonomy and determining their feeding mode (Daley and Budd 2010; Daley et al. 2013; Potin et al. 2023; Bicknell et al. 2023; Potin and Daley 2023). In the Fezouata Shale Fm., the majority of radiodont specimens collected are body parts of the suspension-feeders Aegirocassis benmoulai, Pseudoangustidontus duplospineus Van Roy & Tetlie, 2006 and Pseudoangustidontus izdigua Potin et al., 2023, but, some other undescribed specimens are also interpreted as sediment-sifters (Van Roy et al. 2015b; Potin et al. 2023).

In this study, we describe a new giant radiodont from the Fezouata Biota, and we compare it with Cambrian taxa.

Institutional abbreviations.—MCZ IP, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA; MGL, Naturéum Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles, Département de géologie, Lausanne, Switzerland; NIGPAS, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, China; USNM, U.S. National Museum of Natural History, Washington D.C., USA; YPM IP, Yale Peabody Museum, Yale University, New Haven, USA.

Other abbreviations.—as, auxialiary spines; En, endite; p, podomere; p7En, endite of the podomere seven.

Nomenclatural acts.—This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in ZooBank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A0EB50B1-F032-432F-9F62-A5CFEEF89905.

Material and methods

Fossil specimens.—This study is based on seven specimens from the lower member of the Fezouata Shale Fm. (Lower Fezouata Shale, upper Tremadocian, ca. 478 Ma, Sagenograptus murrayi Biozone) (SOM: table 1, Supplementary Online Material available at http://app.pan.pl/SOM/app70-Potin_etal_SOM.pdf). All the specimens studied come from three collections, the Naturéum Muséum cantonal des sciences naturelles, the Invertebrate Paleontology collections of the Yale Peabody Museum and the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. The MGL, YPM and MCZ material has been collected by authorized and academically recognized Moroccan collector Mohamed Ben Moula (Alnif, Morocco) and his family over the period from 2015 to 2016 (MGL collection), from 2009 to 2015 (YPM collection) and 2019 (MCZ collections). The MGL fossil collection was purchased with funds from the University of Lausanne and the Swiss National Science Foundation, following all regulations for purchases. The fossil collection was transported to Casablanca and subjected to export approval by the Ministry of Energy, Mines and the Environment of the federal government of the Kingdom of Morocco. The shipment was officially approved for export to Switzerland on 11 May 2017, with the relevant export permits curated alongside the collection. Fossils were shipped by sea and land to the University of Lausanne, where they are curated as part of the MGL collection. The collections of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural history were obtained both through collection of specimens by Peter Van Roy (Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium) during field work, and through purchase using dedicated museum funds for the acquisition of scientific collections. Export permits were obtained through the Moroccan Ministry of Energy, Mines and the Environment, with specimens being transported from Casablanca by sea. The collection of the Museum of Comparative Anatomy of Harvard were exported by Brahim Tahiri (Erfoud, Morocco) with the approval of the Ministry of Mines in Rabat (Invoice N. 92/E/21). GPS coordinates are stored with the specimens. These seven specimens are among 221 specimens from the Fezouata Shale Fm. that have been identified as radiodont. One specimen, the holotype of Pseudoangustidontus duplospineus Van Roy & Tetlie, 2006, is from the Floian and the other 220 are from the Tremadocian (SOM: table 2). In addition, data used for NIGPAS 173694 come from Zhu et al. (2021).

Illustration.—A binocular microscope WILD model 308700 (×6.4, 16, 40) was used to examine the specimens and identify their associated microstructures. Photographs were taken with a Canon 800D SLR camera coupled with a Canon EFS 60mm 1:2.8 macro lens. Canon EOS Utility photo software was used to adjust contrast and sharpness. Fossils were photographed under different lighting conditions, including high and low-angle incident and polarized lighting. Camera lucida drawings were made to illustrate and record morphological details. Drawings were digitized using a Wacom Intuos Pro graphic tablet. Figures were prepared with Adobe Photoshop 26.0.0 and Adobe Illustrator 29.0.1 under GJ-MP personal licence.

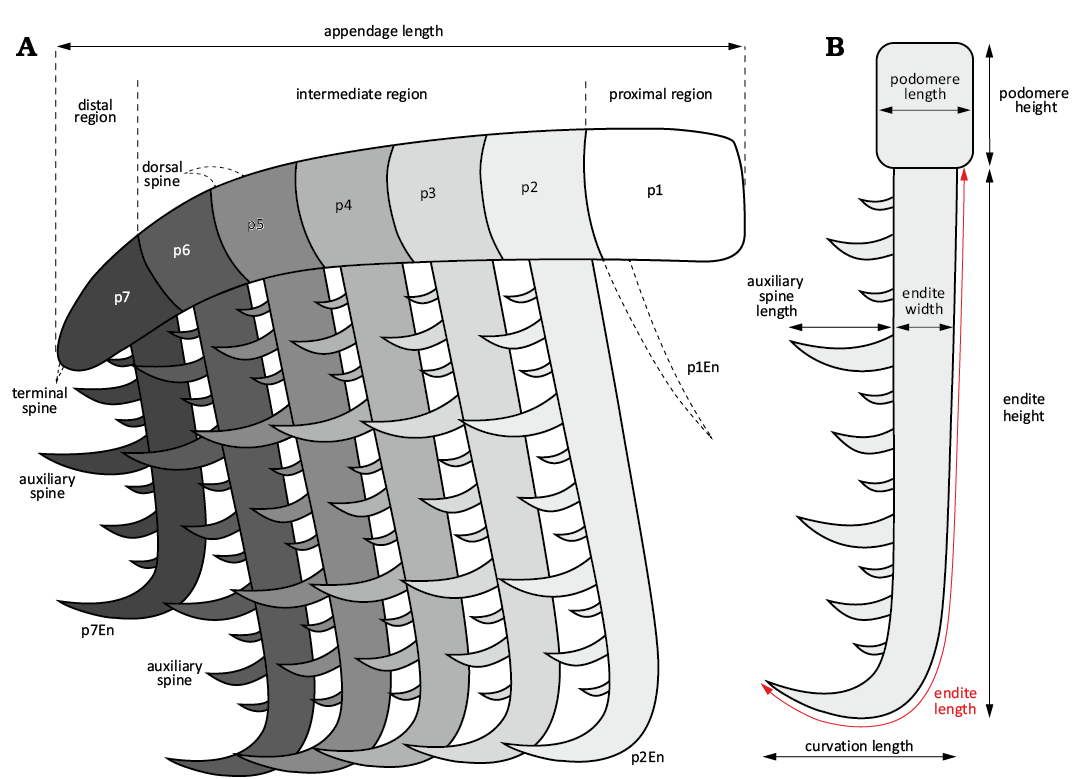

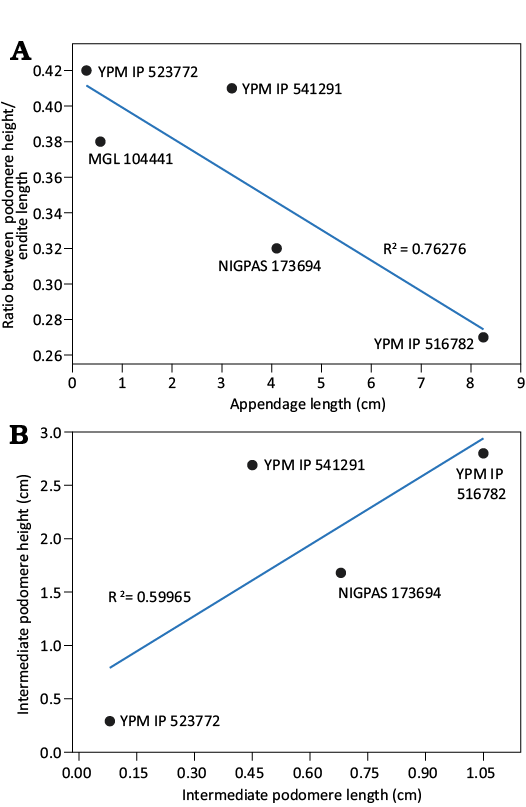

Description, measurements, and body size estimation.—In this paper, we follow the morphology terminology used in Potin and Daley (2023) and Potin et al. (2023) (Fig. 1A). Measurements were made using a digital caliper tool and with the Adobe Photoshop ruler tool. They include lengths, heights and thicknesses of the different features observed on the specimens (Fig. 1B). Note that the endite total length has been measured all along the external outline of the endite (Fig. 1B). A ratio of podomere height over endite length, from the appendage intermediate region (Fig. 1A), was used to investigate possible differences between the type specimens. The height of the endite was also measured (Fig. 1B, SOM: table 1).

Fig. 1. General explanation of the terminology and the measurements applied and used in this study. A. General drawing of a generalised frontal appendage of an hurdiid benthivore sifter. B. Drawing of a podomere and the associated endite showing the different measurements done. Abbreviations: En, endite; p, podomere; p7En, endite of the podomere 7.

The body size estimation was made by comparison with other Hurdiidae taxa for which the full body size is known. We choose to compare with Hurdia victoria (USNM 274159) and Peytoia nathorsti (USNM 274164) from the Burgess Shale (Daley et al. 2013) because these specimens have the frontal appendages attached to the body, and are preserved well enough to do measurements. To compare, we used the ratio of the length of an intermediate region endite of the frontal appendage and to the total length of the body in both taxa. Then, we used both ratios to give a range of body length estimations for Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. This contrasts with previous approaches to estimate the body size of hurdiid radiodonts from partial specimens, which typically used carapace element lengths to complete body length ratios to estimate size of specimens known only from carapace elements (Lerosey-Aubril and Pates 2018).

The graphics showing size variations between specimens was generated from PAST4, version 1.0.6, with the function bivariate regression.

Feeding strategy.—The ecological analysis follows the methodology of Potin et al. (2023). The database from that study was updated with the results of this study, incorporating an additional 86 specimens from the MCZ, and four from the MGL, giving a total number of 211 specimens, all from the Tremadocian (SOM). Specimens for which the feeding strategy could not be identified, as well as the Floian specimen, were not included in the analysis.

We use the term “benthivore” instead of “sediment sifter” previously used in publications about radiodont feeding (e.g., Lerosey-Aubril and Pates 2018; Caron and Moysiuk 2021; Potin and Daley 2023). The term sediment-sifter is defined, according to Fischer et al. (2025), as an organism that feeds on the uppermost layers of the sediment. However, this term is used almost exclusively in radiodont studies. The term benthivore has a wider use in ecology studies (e.g., Bergman and Greenberg 1994; Jay et al. 2014; Grebmeier et al. 2015; Moore and Stabeno 2015). By definition, adult benthivore animals are adapted for bottom feeding, with barbels, lime-like teeth or downturned mouths for example, and have a diet of at least 75% benthic prey (Noble et al. 2007; Stobberup et al. 2009; Milardi et al. 2018).

Systematic palaeontology

Superphylum Panarthropoda Nielsen, 1995

Order Radiodonta Collins, 1996

Family Hurdiidae Lerosey-Aubril & Pates, 2018

Type genus: Hurdia Walcott, 1912, Cambrian Wuliuan Burgess Shale Formation, British Columbia, Canada.

Genera included: Type genus and Aegirocassis Van Roy et al., 2015b; Buccaspinea Pates et al., 2021; Cambroraster Moysiuk & Caron, 2019; Cordaticaris Sun et al., 2020; Mosura Moysiuk & Caron, 2025; Pahvantia Robison & Richards, 1981; Peytoia Walcott, 1911; Pseudoangustidontus Van Roy & Tetlie, 2006; Stanleycaris Caron et al., 2010; Titanokorys Caron & Moysiuk, 2021; Ursulinacaris Pates & Daley, 2019; questionably: Schinderhannes Kühl et al., 2009.

Diagnosis.—See Potin et al. (2023).

Remarks.—McCall (2023) indicated that the family name should be Peytoiidae, replacing Hurdiidae based on precedence. For consistency with previous publications, we have maintained Hurdiidae because of its prevailing usage in radiodont publications, while acknowledging that the systematic validity requires detailed examination in future publications.

Genus Falciscaris nov.

Zoobank LCID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:C9219FF9-96FE-41B3-99B6- 3F8C9724444B.

Etymology: From Latin falx (genitive falcis), scythe, in recognition of the strongly curved shape of the endites tips; and Latinised Greek caris, crab, commonly used in arthropod taxonomy.

Type species: Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., monotypic; see below.

Diagnosis.—Same as species by monotypy.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Fezouata Shale Formation, Sagenograptus murrayi Zone, Tremadocian, Lower Ordovician. Anti-Atlas, Morocco; also in Jiangshanian, Cambrian, Sandu Formation, Guangxi, China.

Falciscaris mumakiana sp. nov.

Figs. 2. 3.

Zoobank LCID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:5B72C323-A3D9-466E-8857- 875E96B45112.

Etymology: Mûmak (plural mûmakil) is a fantasy elephant-like animal from the Tolkien universe Lord of the Rings. They are described as giant animals and are depicted in the third part of the movie trilogy as having 4 long curved tusks equipped with spines, looking like the curved and spiny endite of Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov.

Type material: Holotype: YPM IP 516782. Paratypes: YPM IP 541291, YPM IP 523772, MGL 104441, all articulated frontal appendages. All from the type locality and horizon.

Type locality: North of Zagora (Zagora province), Drâa-Tafilalet region, Morocco.

Type horizon: Lower members of the Fezouata Shale Formation (Lower Ordovician, Tremadocian), Sagenograptus murrayi Zone.

Material.—Type material and isolated endites YPM IP 534284, MCZ IP 202546, and MCZ IP 202543 (other material as single endites), all come from the north of Zagora, from different excavation outcrops of the Lower member of the Fezouata Shale Formation (Tremadocian). GPS coordinates are curated with specimens.

Diagnosis.—Hurdiidae frontal appendage with at least seven podomeres: one proximal, five intermediate and one distal. Proximal podomeres rectangular, taller than long. At least six laminiform endites are present, long ones on five intermediate podomeres and a shorter one distally. Intermediate endites over twice the height of podomeres, all ending in a strongly curved, hook-like tip. Each endite bears dorsally curved auxiliary spines in at least three sizes, alternating such that spines of the same size are never adjacent.

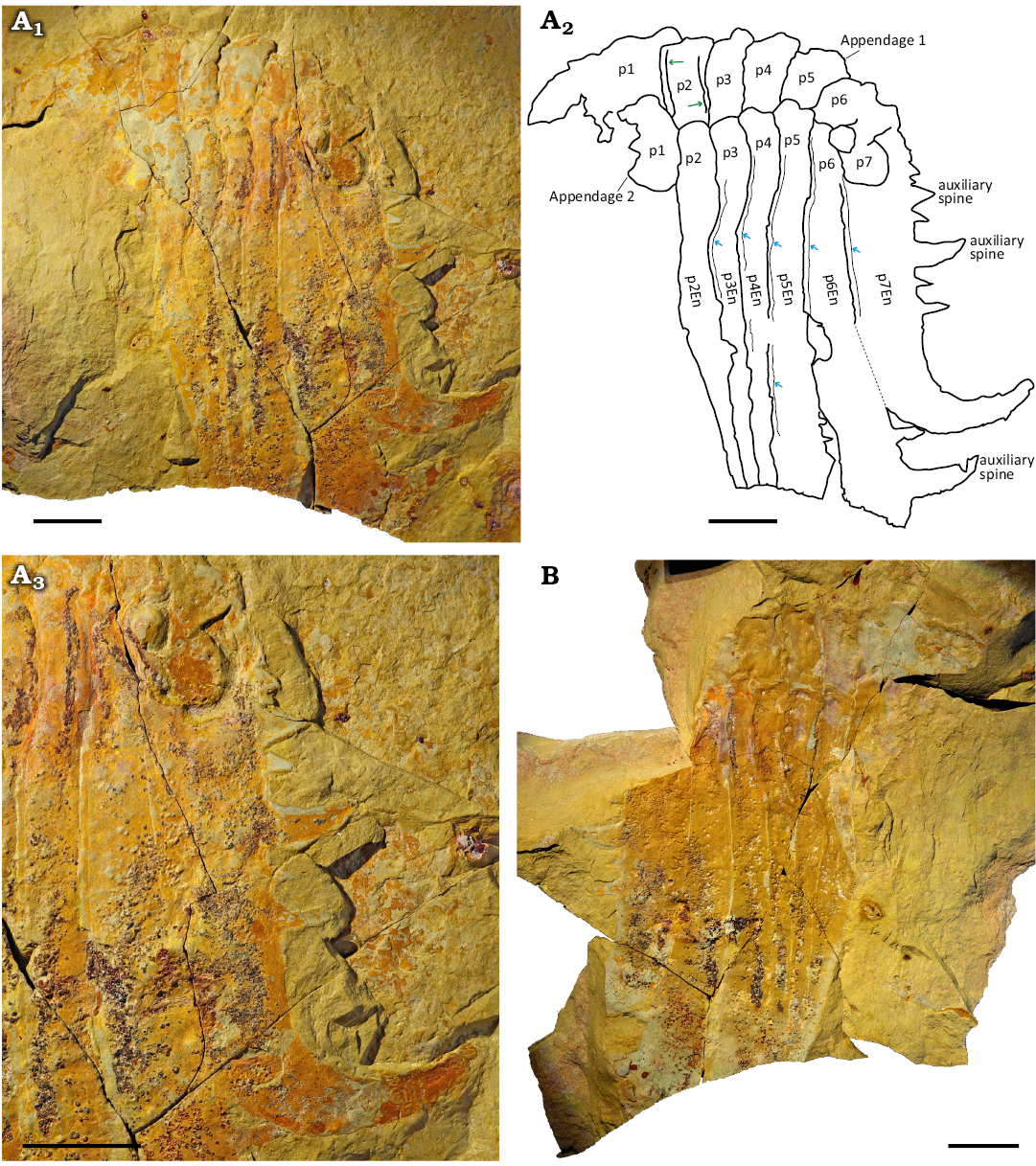

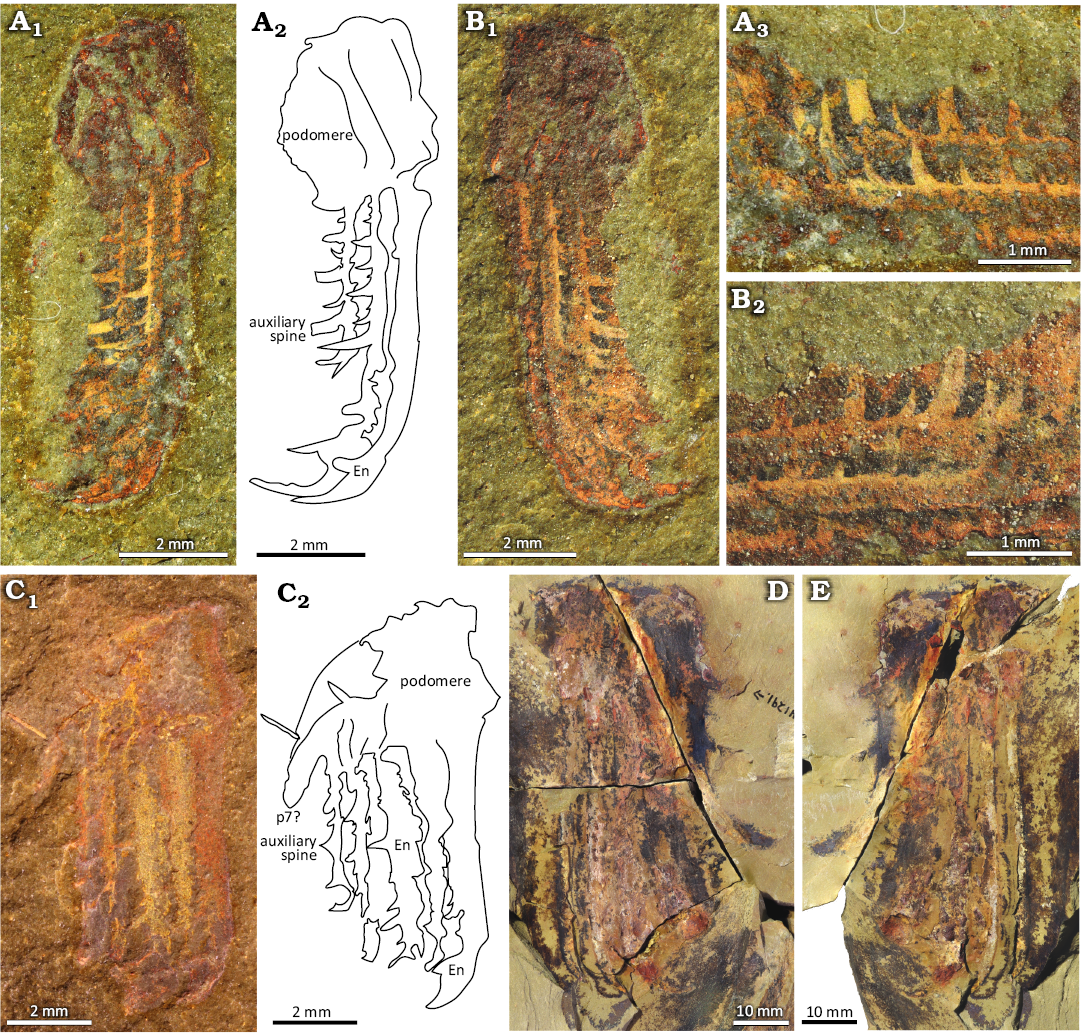

Description.—All type specimens consist of articulated frontal appendages with podomeres and, in some cases, endites directly articulated in complete appendages. Appendage length ranges from 94.7 mm (Fig. 2), to 2.8 mm for (Fig. 3A, B; SOM: table1). The most complete specimen, YPM IP 516782, preserves two appendages, each with seven podomeres including one proximal, five intermediate and one distal (Fig. 2). One appendage overlies the other, in such a way that only one has visible endites. All other specimens show intermediate podomeres (p2 to p6), and possibly a distal podomere (p7) in MGL 104441 (Fig. 3C). Intermediate podomeres are rectangular, with height at least two to three times their length (SOM: table 1). In YPM IP 516782, a narrow ridge is visible between podomeres 1 and 2, and between podomeres 2 and 3, and may represent preservation of the arthrodial membrane or overlapping regions of cuticle (Fig. 3A). The distal podomere is less well preserved, but appears to taper abruptly compared to the intermediate podomeres, and terminates in a blunt (Fig. 3D, E) or rounded (Figs. 2A, 3C) tip.

Fig. 2. Hurdiid radiodont Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. frontal appendage, YPM IP 516782a/b, holotype, from the Fezouata Shale Formation, Lower Ordovician, Morocco. A. Part (YPM IP 516782a) photographed using polarized filter (A1), camera lucida drawing (A2), blue arrows, endite reinforced margin; green arrow, arthrodial membrane; and zoom on the endite of the distal p7 and p7En under polarized filter (A3). B. Counterpart (YPM IP 516782b) photographed using a polarized filter. Abbreviations: En, endite; p, podomere; p7En, endite of the podomere 7. Scale bars 20 mm.

In all specimens, intermediate and distal podomeres bear laminiform endites that curved distally at their tips, giving them a distinct hooked shape (Figs. 2, 3). The endites of the distal podomere are shorter than those on the intermediate podomeres. Endite lengths for intermediate podomeres range from over 98.1 mm on p6En of YPM IP 516782 (Fig. 2) to 5 mm on the endite of the fourth podomere (counting from the left) of YPM IP 523772 (Fig. 3A, B). YPM IP 516782, the larger specimen, has a lower endite length-to-podomere height ratio (0.27) compared to YPM IP 541291 (0.41), YPM IP 523772 (0.42) and MGL 104441 (0.38) (SOM: table 1). Although the intermediate podomere endites are partially broken, p6En (98.1 mm before curvature) is clearly longer than p7En (67.5 mm before curvature; total length 114.1 mm) (Fig. 2, SOM: table 1), indicating that p6En was originally much longer. Similarly, p7En appears shorter in YPM IP 541291.

All endites bear dorsally curved auxiliary spines along their distal margins. Intermediate endites have more than 10 auxiliary spines, while the distal one shows up to seven (Figs. 2, 3). In some well-preserved specimens, three distinct spine sizes are observed—small, medium, and large—with larger spines not extending beyond the curved tip of the endite. Additionally, the endites of YPM IP 516782 each exhibit a reinforced margin visible along the proximal side of the entire endite length, approximately 1 mm thick (Fig. 2A1, A2). YPM IP 516782 has, between podomeres p1, p2 and p3 of the appendage 1, narrow elongated regions interpreted to be arthrodial membrane (Fig. 2A1, A2: green arrow).

Fig. 3. Hurdiid radiodont Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. frontal appendages, paratypes, from the Fezouata Shale Formation, Lower Ordovician, Morocco. A. Part (YPM IP 523772a) photographed using a polarized filter (A1), camera lucida drawing (A2), and zoom on the auxiliary spines (A3). B. Counterpart (YPM IP 523772b) photographed using a polarized filter (B1) and zoom on the auxiliary spines (B2). C. MGL 104441 photographed using a polarized filter (C1) and a camera lucida drawing (C2). D. Part (YPM IP 541291a) photographed using a polarized filter. E. Counterpart (YPM IP 541291b) photographed using a polarized filter. Abbreviation: En, endite.

Remarks.—These specimens are considered as Hurdiidae owing to the presence of a series of unpaired laminiform endites with distally facing auxiliary spines, tall rectangular podomeres, and limited articulated membrane between podomeres. Like other hurdiids, the appendage can also be distinguished into a proximal, intermediate, and distal region (Lerosey-Aubril and Pates 2018; Potin et al. 2023). Falciscaris gen. nov. is distinguished from other hurdiids by its unique endite morphology, the presence of three distinct sizes of auxiliary spines, and its specific podomere count.

It bears seven podomeres; one proximal, five intermediate and one distal; fewer than in other hurdiids genera: Stanleycaris (14), Buccaspinea and Ursulinacaris (12), Peytoia (11), Cambroraster and Cordaticaris (10), and Hurdia (9) (Daley et al. 2009, 2013; Caron et al. 2010; Daley and Legg 2015; Pates et al. 2019, 2021; Moysiuk and Caron 2019, 2021, 2022; Sun et al. 2020). Unlike Ursulinacaris grallae, which has paired endites (Pates et al. 2019), Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. bears one single endite on each intermediate and distal podomeres. The auxiliary spines of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. are robust and therefore, differ from the fine setae of the Aegirocassisinae (Potin et al. 2023), the needle-like spines of Cordaticaris striatus (Sun et al. 2020) and the elongate ones of Titanokorys gainesi (Caron and Moysiuk 2021). Mosura fentoni lacks auxiliary spines or setae entirely (Moysiuk and Caron 2025). The absence of dorsal spines discriminates F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. from the species of Cambroraster, Hurdia, Pahvantia, and Peytoia (Daley et al. 2009, 2013; Daley and Legg 2015; Lerosey-Aubril and Pates 2018; Moysiuk and Caron 2019; Caron and Moysiuk 2021). Notably, F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. is unique in possessing three different sizes of auxiliary spines on each endite and strongly hooked endite tip.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Lower member Fezouata Shale Formation, Sagenograptus murrayi Zone, Tremadocian, Lower Ordovician; Anti-Atlas of Morocco.

Falciscaris cf. mumakiana sp. nov.

2021 undetermined hurdiid; Zhu et al. 2021: 6, fig. 1.

Material.—Articulated frontal appendages NIGPAS 173694 from Guangxi, China. Sandu Formation, Jiangshanian, Cambrian.

Description.—See Zhu et al. (2021).

Remarks.—NIGPAS 173694 is identified as belonging to Hurdiidae in Zhu et al. (2021). In this work we identify it as a Falciscaris cf. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. The size of the specimen is similar to YPM IP 541291, which is the medium-sized specimen for the Fezouata taxon (SOM: table 1). NIGPAS 173694 has the same number of podomeres, seven, including one proximal, five intermediates and one distal, as the Fezouata F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. (i.e., YPM IP 516782) The proximal podomere does not bear an endite, the intermediate podomeres have longer endites than the distal podomere, but the endites are not complete and do not show auxiliary spines, probably due to preservation. The distal endite is better preserved. It is shorter and has a similar hook-shaped termination. The hook of the Chinese F. cf. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. seems shorter than that of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. from Morocco, even accounting for the observation that it is broken at the tip (SOM: table 1). The auxiliary spines are more slender in the Chinese specimen than in the Moroccan ones, but four different sizes can be observed. The smallest auxiliary spines in the Chinese specimen are similar in thickness to setae of other Ordovician hurdiids such as Aegirocassis benmoulai (SOM: table 1). In NIGPAS 173694, the endite length and podomere height ratio is around 0.30, similar to YPM IP 516782 (SOM: table 1).

Results

Measurements and body size estimation.—The specimens of Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. are variable in size (Figs. 2, 3). For example, the endite length in YPM IP 523772 is 5.6 mm while the incomplete endites of YPM IP 516782 are at least up to 100 mm. Some specimens with similar morphological characteristics have intermediate sizes, 7.5 mm and 50 mm in MGL 104441 and YPM IP 541291, respectively (SOM: table 1).

The body length estimation of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., based on the largest appendage specimen, was made using the ratio between endite length and body length in USNM 274159 (Hurdia victoria, Daley et al. 2009: fig. 1a, b) and USNM 274164 (Peytoia nathorsti, Daley et al. 2013: fig. 14a–c). Then endite length of the Hurdia specimen is 25.5 mm for a body length of 178.2 mm, that gives a ratio of 0.14. For Peytoia the endite is 11 mm long and the body length is 126.6 mm, giving a ratio of 0.08. In the biggest specimen of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., YPM IP 516782, the longest endite is 98.1 mm long, giving an estimate of between 700–1225 mm for its body length (SOM: fig. 1, table 1).

Feeding strategy proportion.—In total, there are 211 radiodont frontal appendage remains for which we could identify the feeding strategy. More than 90% of the collection corresponds to suspension-feeding frontal appendages and the rest are benthivores (SOM: table 2). The most common taxon of the assemblage is Aegirocassis benmoulai, known from 90 specimens, followed by species of Pseudoangustidontus with 56 specimens (SOM: table 2). Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. is known from seven specimens, out of a total of 16 benthivore specimens (SOM: table 2).

Discussion

Ecology.—All radiodonts are widely interpreted as nektonic predators exhibiting diverse feeding strategies, including raptorial predation (e.g., Anomalocaris canadensis), benthivores (Hurdia victoria), and suspension-feeders (Aegirocassisinae) (Daley et al. 2009, 2013; Van Roy et al. 2015b; Guo et al. 2019; Caron and Moysiuk 2021; Potin et al. 2023; Bicknell et al. 2023; Potin and Daley 2023). All of these feeding strategies have been interpreted primarily based on the morphology of frontal appendages mainly, but also completed by studies of the oral cones, which played a key role in prey capture and food transfer (Guo et al. 2019; Bicknell et al. 2023; Potin and Daley 2023). In benthivore radiodonts, the low number of appendage podomeres (compared to 13 in Anomalocaris species), the length of the endites, and the robustness of the auxiliary spines, suggest an adaptation for disturbing and/or foraging within sediments (Daley and Edgecombe 2014; Moysiuk and Caron 2021; Wu et al. 2021; Potin and Daley 2023). This could be by waving the appendage over the sediment to reveal prey, or by foraging through the sediment. According to Caron and Moysiuk (2021), there are two types of benthivores depending on the morphology and organization of the auxiliary spines. The morphology of the endites of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. suggests that it is a macrobenthivore because of the large and widely-spaced auxiliary spines, similar to the species of Hurdia and Peytoia, while microbenthivores, like Titanokorys gainesi and possibly Cambroraster falcatus (De Vivo et al. 2021, considering it as a suspension-feeder), have thinner auxiliary spines that are more closely spaced (Caron and Moysiuk 2021).

Benthivory is a feeding mode known in modern arthropods such as pycnogonids, especially in deep-sea forms that consume endobenthic meiofauna (Dietz et al. 2018). Some fossil decapod crustaceans possess spinose appendages supposedly used to dig into the sediment for feeding on endobenthic prey (e.g., Stamhuis et al. 1998; Schweitzer et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2018). A similar feeding functionality to that seen in decapods has been proposed for Cambroraster falcatus (Moysiuk and Caron 2019). In a totally different group, walruses are another modern ecological analogue, being giant benthivores from polar regions. This macro-mammal uses their front flipper in waving motions to produce a water pulse in order to remove the top layers of sediment, and capture infaunal invertebrates with suction into the mouth (Levermann et al. 2003; Jay et al. 2014; Grebmeier et al. 2015; Moore and Stabeno 2015). The suction of prey into the mouth has been proposed for radiodonts based on the functional morphology of their oral cones (Daley and Bergström 2012), and for Cambroraster falcatus this was evidenced by similarities between its oral cone and the circular oral aperture with planar profile in suction feeding aquatic vertebrates (Moysiuk and Caron 2019).

The frontal appendages of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. show striking morphological similarities with the chelicerae fingers of Silurian and Devonian pterygotid eurypterids (e.g., Jaekelopterus rhenaniae), especially in the arrangement of principal, intermediate, and elongated terminal denticles (Braddy et al. 2008: fig. 1e; Lamsdell 2025: fig. 68). The major difference is that the chelicerae of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, and the other pterygotids, are articulated into two fingers (Waterston 1964; Braddy et al. 2008; Bicknell et al. 2022; Lamsdell 2025), whereas the endites of radiodonts are organized in series. Chelicerae of pterygotids have this morphology probably to grasp and crush prey (Bicknell et al. 2022), while F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. probably used its appendages to forage the sediment. The morphological similarity evolved to serve different functions, suggesting this is not a case of functional convergence.

Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. is known from a proportionally greater number of articulated frontal appendages in comparison with suspension-feeding radiodonts. Indeed, four specimens out of seven are almost completely articulated, while the suspension-feeding radiodonts are much more disarticulated, mainly represented by isolated endites and only a few complete specimens (Potin et al. 2023). Such difference in preservation could be linked to their mode of life. Suspension-feeders are expected to have lived up in the water column, close to the surface where plankton is abundant (Moore et al. 2003; Savoca et al. 2021). When their carcasses fell, they could have been affected by several biostratinomic processes such as transportation and flotation, which increase the time before burial and therefore the extent of decay, disarticulation and scavenging (as seen for the carcasses of present-day suspension-feeding vertebrates; e.g., Tucker et al. 2019). It should also be noted that this also applies to radiodont suspension-feeder moults. In turn, nektobenthic benthivores lived closer to the seafloor where the deposition of their carcasses and moults will be less affected.

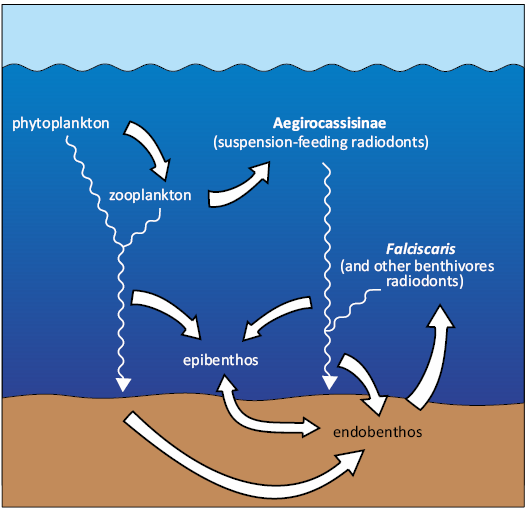

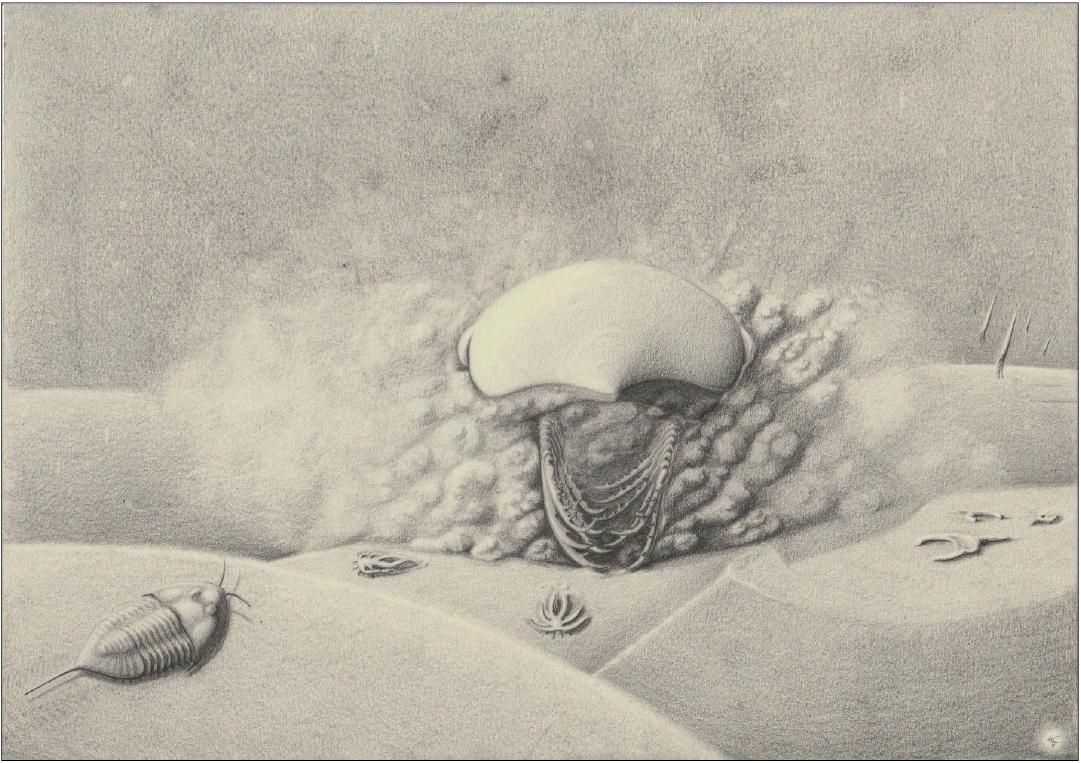

Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. provides further insight into the organization of Fezouata ecosystem, especially the ecological role of radiodonts (Fig. 4). Suspension-feeding Aegirocassisinae likely consumed mesoplankton (Potin and Daley 2023), mainly composed of zooplankton, such as early-stage trilobitomorphs or marrellomorphs (Perrier et al. 2015; Pérez-Peris et al. 2021a; Laibl et al. 2023a, b). The zooplankton consumes phytoplankton and together they provide nutrients for benthic sessile suspension-feeders such as echinoderms, bivalves, brachiopods, and possibly the small euchelicerate Setapedites (Polechová 2016; Lefebvre et al. 2016a; Saleh et al. 2018, 2020, 2024a; Nanglu et al. 2023; Dupichaud et al. 2023; Richards et al. 2024; Lustri et al. 2024, 2025). The benthic fauna also included scavengers and predators (e.g., trilobites, marrellomorphs, aglaspids) (Vidal 1998a, b; Grebmeier et al. 2015; Perrier et al. 2015; Moore and Stabeno 2015; Ortega-Hernández et al. 2016; Vannier et al. 2019; Saleh et al. 2021; Pérez-Peris et al. 2021a, b; Laibl et al. 2023a, b), as well as endobenthic animals like priapulids, paleoscolecids and some arthropods (Saleh et al. 2024a; Nanglu and Ortega-Hernández 2024). These communities likely served as prey for benthivorous radiodonts such as F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., which were supposedly well-adapted to sediment foraging, as mentioned previously. Finally, as some of the largest animals in the Fezouata Biota, radiodonts themselves especially F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. and Aegirocassisinae may have formed critical resource for secondary benthic consumers. Their moults and carcasses could have supported benthic detritivore communities in a manner analogous to modern whale or Mesozoic ichthyosaur falls, acting as nutrient hotspots in otherwise low-nutrient environments (Dick 2015; Smith et al. 2015; Van Roy et al. 2015b; Potin et al. 2023).

Fig. 4. Ecological interactions of radiodont community from the Fezouata Biota in their environment. Thick arrows indicate the feeding interactions between community components, and wavy arrows represent carcass fall of pelagic/benthic organisms.

Ontogeny.—The Fezouata Biota is known for preserving some ontogenetic series, with the best-known examples found in arthropods like marrellomorphs and trilobites (Laibl et al. 2023a, b). Data from Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. (SOM: table 1) suggests that size variation among the available specimens reflects different ontogenetic stages. Throughout the growth series, the morphology and organization of auxiliary spines remain consistent. Minor variations observed include a decreased podomere height-to-endite length ratio in later stages (Fig. 5, SOM: table 1), and a thinner podomere profile in early-stage specimens such as YPM IP 523772 (Fig. 5). However, these differences may partially result from taphonomic distortion, for example, due to oblique burial orientation. Despite the limited sample size, the consistent spine morphology and overall appendage architecture across specimens support the interpretation that they represent a single radiodont taxon at various developmental stages. The consistent morphology and organization of the auxiliary spines throughout the growth series suggest that the growth of the appendage could be isometric. Isometric growth in radiodonts is particularly well-documented in another radiodont, Amplectobelua symbrachiata, known by a more complete ontogenetic series of specimens (Wu et al. 2024b). Stanleycaris hirpex from the Burgess Shale (Moysiuk and Caron 2022) has an ontogenetic series of specimens of complete bodies, some with frontal appendages, that do not show much morphological variation during growth as well (Moysiuk and Caron 2021, 2022). These two documented examples are consistent with our observations on the small sample size of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., and further support the inference that isometric growth is common in radiodont ontogeny.

Fig. 5. Linear bivariate regression graphs of the type material. A. Ratio between podomere height and endite length compared with the appendage length. B. Podomere length as a function of podomere height.

Giantism in the Early Ordovician.—The radiodont assemblage of the Fezouata Biota is largely dominated by suspension-feeders, which encompass approximatively 92% of collected material, with three species and 121 specimens (Potin et al. 2023). The new data collected allow us to confirm this trend with the same percentage out of the total of 211 specimens. The dominance of suspension-feeding radiodonts in the community aligns with the “Ordovician Plankton Revolution”, which led to an increase of the abundance and diversity of plankton in the fossil record from the Furongian, late Cambrian, into the Ordovician (Servais et al. 2010, 2016; Potin et al. 2023; Jamart et al. 2025; Lustri et al. 2025). This is a possible explanation for the gigantism and abundance of Aegirocassisinae because giant animals need a lot of resources to sustain their large size and meet their metabolic demands, so the abundance of pelagic prey fosters their emergence (Moore et al. 2003; Pimiento et al. 2019; Savoca et al. 2021; Potin et al. 2023). The increase in plankton also increased the biomass in the benthos, giving a stronger pelagic-benthic coupling (Grebmeier et al. 2015). In the Fezouata Shale Fm., the benthos described is diverse and abundant, with echinoderms, worms and arthropods for example, all of which are potential prey for benthivores (Grebmeier et al. 2015; Lefebvre et al. 2016b; Saleh et al. 2018; Richards et al. 2024). The abundance of resources in the benthos could promote the appearance of big benthivores. Despite this increase of resources, the abundance of benthivores radiodonts in the Fezouata Biota is low compared to other early Paleozoic biotas such as that of the Burgess Shale Formation, from which hundreds of them have been found and studied (Walcott 1908; Briggs 1979; Whittington and Briggs 1985; Daley et al. 2009, 2013; Moysiuk and Caron 2019, 2021, 2022; Caron and Moysiuk 2021; Potin and Daley 2023). In the case of F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., the total number of remains consists of only seven specimens, but the size is relatively huge compared to most other radiodonts. The comparison with the proportion between the endite length and the body length of species of Peytoia and Hurdia suggests a size estimation of around a meter (between 70 cm and 122 cm) for F. mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., and the size could be even bigger considering the measure was made on an incomplete endite, which was still the largest. Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., the 43rd radiodont species formally described, is therefore one of the largest, and one of the largest animals of the Fezouata Biota after the Aegirocassisinae (Paterson et al. 2023; Potin et al. 2023; Potin and Daley 2023; Wu et al. 2024a, c; Moysiuk and Caron 2025).

Other possible benthivorous radiodonts have been found in the Fezouata Biota and some of them have been figured but not yet formally described (Van Roy and Briggs 2011). The sizes of these appendages are smaller. In the Floian of the Fezouata Shale, huge carapaces, likely from radiodonts have also been found (Saleh et al. 2022). Outside of the Fezouata Biota, the only other Ordovician radiodont described is a unique small specimen from the Afon Gam Biota, in the Avalonia paleocontinent and in a temperate zone (Pates et al. 2020; Cocks and Torsvik 2021).

In the Cambrian, the biggest animals known are radiodonts. Some relatively huge raptorial radiodont species are considered as giant apex predators of the ecosystems, such as Anomalocaris canadensis or species of Amplectobelua (Daley and Edgecombe 2014; Cong et al. 2017). Cambrian benthivores could reach massive size (~50 cm) compared to the rest of the ecosystem, like Titanokorys from the Burgess Shale (Caron and Moysiuk 2021). The presence of raptorial radiodonts in the Cambrian is one of the major differences with the Fezouata Shale and the rest of the Early Ordovician, because none have been found so far from these younger localities. It could suggest the decline of this feeding strategy among radiodonts, probably because of the competition with other predators such as eurypterids or cephalopods (Kröger and Lefebvre 2012; Van Roy et al. 2015a; Pates et al. 2020; Potin et al. 2023).

Conclusions

This study describes Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov., a new hurdiid radiodont from the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Shale Formation (Fig. 6) represented by seven frontal appendage specimens. The appendage morphology is distinctive among radiodonts, characterized by three size classes of auxiliary spines on the same endite and a strongly curved distal tip features reminiscent of the cheliceral fingers of Devonian pterygotid eurypterids. Despite of the limited specimens, this species exhibits a large variation in specimen size, with the largest specimens having endites more than ten times longer than smaller ones, yet maintaining consistent morphology throughout ontogeny (likely isometric growth). Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. is interpreted as a nektobenthic benthivore, based on its elongated endites and robust auxiliary spines. Benthivores represent a minority in the radiodont community of the Fezouata Shale Fm., largely dominated by the suspension-feeding Aegirocassisinae. However, both of them have experienced gigantism likely as a response to the “Ordovician Plankton Revolution”, which led to an increase in the availability of resources for suspension-feeders, and made pelagic-benthic coupling stronger to the advantage of benthic and nektobenthic animals.

Fig. 6. Artistic life reconstruction (by AT) of the hurdiid radiodont Falciscaris mumakiana gen. et sp. nov. Apart from the frontal appendages, the reconstruction is based on other related hurdiids.

Authors’ contributions

GJMP, PC and ACD designed the original project. GJMP and PC described the fossils. GJMP interpreted, discussed, and wrote the manuscript with the help of all authors. GJMP performed the analyses with the help of PG, and prepared the figures with the help of PC, PG and ACD. The reconstruction has been made by AT.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Susan Butts and Jessica Utrup (YPM) for facilitating access to the YPM IP specimens, by sending specimens to the University of Lausanne (Switzerland). We would like to thank Javier Ortega-Hernández, Jared Richards, Jessica Cundiff, Cyrus Green, Mark D. Renczkowski and the rest of the paleontology group of the MCZ and Department of Organismic and Evolutionary of the Harvard University (Cambridge, USA) for access to the MCZ IP collections and helpful discussions. We are also grateful to Gene Hunt (USNM) for providing access to the USNM specimens used for the body size estimation. We thank the ANOM Lab members (UNIL), Christian Klug (University of Zurich, Switzerland) and Elias Samankassou (University of Geneva, Switzerland) for their precious help and discussions. Finally, we thank the reviewers Russell Bicknell (American Museum of Natural History, New York City, USA) and Donjing Fu (Northwest University, Xi’an, China) for their constructive and kind reviews helping to improve the manuscript. This research was funded by the Canton de Vaud and the Swiss National Science Foundation, grant number 205321_179084 entitled “Arthropod Evolution during the Ordovician Radiation: Insights from the Fezouata Biota” and awarded to ACD. YW acknowledges support from a Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship and the National Science Foundation of China (42202011). We are also grateful for Swiss Systematic Society financial support, with their Student Travel Grant, allowing the visit of Burgess Shale collections.

Editor: Andrzej Kaim

References

Bergman, E. and Greenberg, L.A. 1994. Competition between a planktivore, a benthivore, and a species with ontogenetic diet shifts. Ecology 75: 1233–1245. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Schmidt, M., Rahman, I.A., Edgecombe, G.D., Gutarra, S., Daley, A.C., Melzer, R.R., Wroe, S., and Paterson, J.R. 2023. Raptorial appendages of the Cambrian apex predator Anomalocaris canadensis are built for soft prey and speed. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 290 (2002): 20230638. Crossref

Bicknell, R.D.C., Simone, Y., van der Meijden, A., Wroe, S., Edgecombe, G.D., and Paterson, J.R. 2022. Biomechanical analyses of pterygotid sea scorpion chelicerae uncover predatory specialisation within eurypterids. PeerJ 10: e14515. Crossref

Braddy, S.J., Poschmann, M., and Tetlie, O.E. 2008. Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod. Biology Letters 4: 106–109. Crossref

Briggs, D.E.G. 1979. Anomalocaris, the largest known Cambrian arthropod. Palaeontology 22: 631–664.

Caron, J.-B. and Moysiuk, J. 2021. A giant nektobenthic radiodont from the Burgess Shale and the significance of hurdiid carapace diversity. Royal Society Open Science 8 (9): 210664. Crossref

Caron, J.-B., Gaines, R.R., Mángano, M.G., Streng, M., and Daley, A.C. 2010. A new Burgess Shale-type assemblage from the “thin” Stephen Formation of the southern Canadian Rockies. Geology 38: 811–814. Crossref

Cocks, L.R.M. and Torsvik, T.H. 2021. Ordovician palaeogeography and climate change. Gondwana Research 100: 53–72. Crossref

Collins, D. 1996. The “evolution” of Anomalocaris and its classification in the arthropod class Dinocarida (nov.) and order Radiodonta (nov.). Journal of Paleontology 70: 280–293. Crossref

Cong, P., Daley, A.C., Edgecombe, G.D., and Hou, X. 2017. The functional head of the Cambrian radiodontan (stem-group Euarthropoda) Amplectobelua symbrachiata. BMC Evolutionary Biology 17: 1–23. Crossref

Daley, A.C. and Bergström, J. 2012. The oral cone of Anomalocaris is not a classic “peytoia”. Naturwissenschaften 99: 501–504. Crossref

Daley, A.C. and Budd, G.E. 2010. New anomalocaridid appendages from the Burgess Shale, Canada. Palaeontology 53: 721–738. Crossref

Daley, A.C. and Edgecombe, G.D. 2014. Morphology of Anomalocaris canadensis from the Burgess Shale. Journal of Paleontology 88: 68–91. Crossref

Daley, A.C. and Legg, D.A. 2015. A morphological and taxonomic appraisal of the oldest anomalocaridid from the lower Cambrian of Poland. Geological Magazine 152: 949–955. Crossref

Daley, A.C., Antcliffe, J.B., Drage, H.B., and Pates, S. 2018. Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: 5323–5331. Crossref

Daley, A.C., Budd, G.E., and Caron, J.-B. 2013. Morphology and systematics of the anomalocaridid arthropod Hurdia from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia and Utah. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 11: 743–787. Crossref

Daley, A.C., Budd, G.E., Caron, J.-B., Edgecombe, G.D., and Collins, D. 2009. The Burgess Shale anomalocaridid Hurdia and its significance for early euarthropod evolution. Science 323: 1597–1600. Crossref

De Vivo, G., Lautenschlager, S., and Vinther, J. 2021. Three-dimensional modelling, disparity and ecology of the first Cambrian apex predators. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 288 (1955): 20211176. Crossref

Dick, D.G. 2015. An ichthyosaur carcass-fall community from the Posidonia Shale (Toarcian) of Germany. Palaios 30: 353–361. Crossref

Dietz, L., Dömel, J.S., Leese, F., Lehmann, T., and Melzer, R.R. 2018. Feeding ecology in sea spiders (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida): what do we know? Frontiers in Zoology 15 (1): 7. Crossref

Dupichaud, C., Lefebvre, B., Milne, C.H., Mooi, R., Nohejlová, M., Roch, R., Saleh, F., and Zamora, S. 2023. Solutan echinoderms from the Fezouata Shale Lagerstätte (Lower Ordovician, Morocco): Diversity, exceptional preservation, and palaeoecological implications. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1290063. Crossref

Edgecombe, G.D. 2020. Arthropod origins: integrating paleontological and molecular evidence. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51: 1–25. Crossref

Fischer, M., Lewis, C., Hawkins, J., and Roberts, C. 2025. A Functional Assessment of Fish as Bioturbators and Their Vulnerability to Local Extinction. Marine Environmental Research 209: 107158. Crossref

Friedman, M., Shimada, K., Martin, L.D., Everhart, M.J., Liston, J., Maltese, A., and Triebold, M. 2010. 100-million-year dynasty of giant planktivorous bony fishes in the Mesozoic seas. Science 327: 990–993. Crossref

Grebmeier, J.M., Bluhm, B.A., Cooper, L.W., Danielson, S.L., Arrigo, K.R., Blanchard, A.L., Clarke, J.T., Day, R.H., Frey, K.E., Gradinger, R.R., Kędra, M., Konar, B., Kuletz, K.J., Lee, S.H., Lovvorn, J.R., Norcross, B.L., and Okkonen, S.R. 2015. Ecosystem characteristics and processes facilitating persistent macrobenthic biomass hotspots and associated benthivory in the Pacific Arctic. Progress in Oceanography 136: 92–114. Crossref

Guo, J., Pates, S., Cong, P., Daley, A.C., Edgecombe, G.D., Chen, T., and Hou, X. 2019. A new radiodont (stem Euarthropoda) frontal appendage with a mosaic of characters from the Cambrian (Series 2 Stage 3) Chengjiang biota. Papers in Palaeontology 5: 99–110. Crossref

Jamart, V., Pas, D., Adatte, T., Spangenberg, J.E., Laibl, L., and Daley, A.C. 2025. The Cambrian ROECE and DICE carbon isotope excursions in western Gondwana (Montagne Noire, southern France): Implications for regional and global correlations of the Miaolingian Series. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 670: 112951. Crossref

Jay, C.V., Grebmeier, J.M., Fischbach, A.S., McDonald, T.L., Cooper, L.W., and Hornsby, F. 2014. Pacific walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens) resource selection in the northern Bering Sea. PLOS ONE 9 (4): e93035. Crossref

Jones, W.T., Feldmann, R.M., Hannibal, J.T., Schweitzer, C.E., Garland, M.C., Maguire, E.P., and Tashman, J.N. 2018. Morphology and paleoecology of the oldest lobster-like decapod, Palaeopalaemon newberryi Whitfield, 1880 (Decapoda: Malacostraca). Journal of Crustacean Biology 38: 302–314. Crossref

Klug, C., De Baets, K., Kröger, B., Bell, M.A., Korn, D., and Payne, J.L. 2015. Normal giants? Temporal and latitudinal shifts of Palaeozoic marine invertebrate gigantism and global change. Lethaia 48: 267–288. Crossref

Klug, C., Fuchs, D., Pohle, A., Korn, D., De Baets, K., Hoffmann, R., Ware, D., and Ward, P.D. 2025. Cephalopod body size and macroecology through deep time. Scientific Reports 15: 30736. Crossref

Kröger, B. and Lefebvre, B. 2012. Palaeogeography and palaeoecology of early Floian (Early Ordovician) cephalopods from the Upper Fezouata Formation, Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Fossil Record 15 : 61–75. Crossref

Kubodera, T. and Mori, K. 2005. First-ever observations of a live giant squid in the wild. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272: 2583–2586. Crossref

Kühl, G., Briggs, D.E.G., and Rust, J. 2009. A great-appendage arthropod with a radial mouth from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate, Germany. Science 323: 771–773. Crossref

Laibl, L., Drage, H.B., Pérez-Peris, F., Schöder, S., Saleh, F., and Daley, A.C. 2023a. Babies from the Fezouata Biota: Early developmental trilobite stages and their adaptation to high latitudes. Geobios 81: 31–50. Crossref

Laibl, L., Gueriau, P., Saleh, F., Pérez-Peris, F., Lustri, L., Drage, H.B., Bath Enright, O.G., Potin, G.J.-M., and Daley, A.C. 2023b. Early developmental stages of a Lower Ordovician marrellid from Morocco suggest simple ontogenetic niche differentiation in early euarthropods. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1232612. Crossref

Lamsdell, J.C. 2025. Codex Eurypterida: A Revised Taxonomy Based on Concordant Parsimony and Bayesian Phylogenetic Analyses. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 2025 (473): 1–196. Crossref

Lefebvre, B., Allaire, N., Guensburg, T.E., Hunter, A.W., Kouraïss, K., Martin, E.L.O., Nardin, E., Noailles, F., Pittet, B., Sumrall, C.D., and Zamora, S. 2016a. Palaeoecological aspects of the diversification of echinoderms in the Lower Ordovician of central Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 460: 97–121. Crossref

Lefebvre, B., Lerosey-Aubril, R., Servais, T., and Van Roy, P. 2016b. The Fezouata Biota: an exceptional window on the Cambro-Ordovician faunal transition. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 460: 1–6. Crossref

Lerosey-Aubril, R. and Pates, S. 2018. New suspension-feeding radiodont suggests evolution of microplanktivory in Cambrian macronekton. Nature Communications 9 (1): 3774. Crossref

Levermann, N., Galatius, A., Ehlme, G., Rysgaard, S., and Born, E.W. 2003. Feeding behaviour of free-ranging walruses with notes on apparent dextrality of flipper use. BMC Ecology 3: 1–13. Crossref

Lustri, L., Collantes, L., Esteves, C.J.P., O’Flynn, R.J., Saleh, F., and Liu, Y. 2025. A hypothesis on suspension feeding in early chelicerates (Offacolidae). Diversity 17: 412. Crossref

Lustri, L., Gueriau, P., and Daley, A.C. 2024. Lower Ordovician synziphosurine reveals early euchelicerate diversity and evolution. Nature Communications 15 (1): 3808. Crossref

McCall, C.R.A. 2023. A large pelagic lobopodian from the Cambrian Pioche Shale of Nevada. Journal of Paleontology 97: 1009–1024. Crossref

Milardi, M., Lanzoni, M., Gavioli, A., Fano, E.A., and Castaldelli, G. 2018. Long-term fish monitoring underlines a rising tide of temperature tolerant, rheophilic, benthivore and generalist exotics, irrespective of hydrological conditions. Journal of Limnology 77: 266–275. Crossref

Mironenko, A.A. 2020. Endocerids: suspension feeding nautiloids? Historical Biology 32: 281–289. Crossref

Moore, S.E. and Stabeno, P.J. 2015. Synthesis of Arctic Research (SOAR) in marine ecosystems of the Pacific Arctic. Progress in Oceanography 136: 1–11. Crossref

Moore, S.E., Grebmeier, J.M., and Davies, J.R. 2003. Gray whale distribution relative to forage habitat in the northern Bering Sea: current conditions and retrospective summary. Canadian Journal of Zoology 81: 734–742. Crossref

Moysiuk, J. and Caron, J.-B. 2019. A new hurdiid radiodont from the Burgess Shale evinces the exploitation of Cambrian infaunal food sources. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 286 (1908): 20191079. Crossref

Moysiuk, J. and Caron, J.-B. 2021. Exceptional multifunctionality in the feeding apparatus of a mid-Cambrian radiodont. Paleobiology 47: 704–724. Crossref

Moysiuk, J. and Caron, J.-B. 2022. A three-eyed radiodont with fossilized neuroanatomy informs the origin of the arthropod head and segmentation. Current Biology 32 (15): 3302–3316.e2. Crossref

Moysiuk, J. and Caron, J.-B. 2025. Early evolvability in arthropod tagmosis exemplified by a new radiodont from the Burgess Shale. Royal Society Open Science 12: 242122. Crossref

Nanglu, K. and Ortega-Hernández, J. 2024. Post-Cambrian survival of the tubicolous scalidophoran Selkirkia. Biology Letters 20 (3): 20240042. Crossref

Nanglu, K., Waskom, M.E., Richards, J.C., and Ortega-Hernández, J. 2023. Rhabdopleurid epibionts from the Ordovician Fezouata Shale biota and the longevity of cross-phylum interactions. Communications Biology 6 (1): 1002. Crossref

Nielsen, C. 1995. Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla. 467 pp. Oxford University Press.

Noble, R.A.A., Cowx, I.G., Goffaux, D., and Kestemont, P. 2007. Assessing the health of European rivers using functional ecological guilds of fish communities: standardising species classification and approaches to metric selection. Fisheries Management and Ecology 14: 381–392.

Ortega-Hernández, J., Van Roy, P., and Lerosey-Aubril, R. 2016. A new aglaspidid euarthropod with a six-segmented trunk from the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Konservat-Lagerstätte, Morocco. Geological Magazine 153: 524–536. Crossref

Paterson, J.R., García-Bellido, D.C., and Edgecombe, G.D. 2023. The early Cambrian Emu Bay Shale radiodonts revisited: morphology and systematics. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 21 (1): 2225066. Crossref

Pates, S. and Daley, A.C. 2019. The Kinzers Formation (Pennsylvania, USA): the most diverse assemblage of Cambrian Stage 4 radiodonts. Geological Magazine 156: 1233–1246. Crossref

Pates, S., Botting, J.P., McCobb, L.M.E., and Muir, L.A. 2020. A miniature Ordovician hurdiid from Wales demonstrates the adaptability of Radiodonta. Royal Society Open Science 7 (6): 200459. Crossref

Pates, S., Daley, A.C., and Butterfield, N.J. 2019. First report of paired ventral endites in a hurdiid radiodont. Zoological Letters 5 (1): 18. Crossref

Pates, S., Lerosey-Aubril, R., Daley, A.C., Kier, C., Bonino, E., and Ortega-Hernández, J. 2021. The diverse radiodont fauna from the Marjum Formation of Utah, USA (Cambrian: Drumian). PeerJ 9: e10509. Crossref

Pérez-Peris, F., Laibl, L., Lustri, L., Gueriau, P., Antcliffe, J.B., Bath Enright, O.G., and Daley, A.C. 2021a. A new nektaspid euarthropod from the Lower Ordovician strata of Morocco. Geological Magazine 158: 509–517. Crossref

Pérez-Peris, F., Laibl, L., Vidal, M., and Daley, A.C. 2021b. Systematics, morphology, and appendages of an Early Ordovician pilekiine trilobite Anacheirurus from Fezouata Shale and the early diversification of Cheiruridae. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 66: 857–877.

Perrier, V., Williams, M., and Siveter, D.J. 2015. The fossil record and palaeoenvironmental significance of marine arthropod zooplankton. Earth-Science Reviews 146: 146–162. Crossref

Pimiento, C., Cantalapiedra, J.L., Shimada, K., Field, D.J., and Smaers, J.B. 2019. Evolutionary pathways toward gigantism in sharks and rays. Evolution 73: 588–599. Crossref

Polechová, M. 2016. The bivalve fauna from the Fezouata Formation (Lower Ordovician) of Morocco and its significance for palaeobiogeography, palaeoecology and early diversification of bivalves. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 460: 155–169. Crossref

Potin, G.J.-M. and Daley, A.C. 2023. The significance of Anomalocaris and other Radiodonta for understanding paleoecology and evolution during the Cambrian Explosion. Frontiers in Earth Science 11: 1160285. Crossref

Potin, G.J.-M., Gueriau, P., and Daley, A.C. 2023. Radiodont frontal appendages from the Fezouata Biota (Morocco) reveal high diversity and ecological adaptations to suspension-feeding during the Early Ordovician. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1214109. Crossref

Richards, J.C., Nanglu, K., and Ortega-Hernández, J. 2024. The Fezouata Shale Formation biota is typical for the high latitudes of the Early Ordovician—a quantitative approach. Paleobiology 50: 226–238. Crossref

Robison, R.A. and Richards, B.C. 1981. Larger bivalve arthropods from the Middle Cambrian of Utah. Kansas Paleontological Contributions 106: 1–28.

Saleh, F., Antcliffe, J.B., Birolini, E., Candela, Y., Corthésy, N., Daley, A.C., Dupichaud, C., Gibert, C., Guenser, P., Laibl, L., Lefebvre, B., Michel, S., and Potin, G.J.-M. 2024a. Highly resolved taphonomic variations within the Early Ordovician Fezouata Biota. Scientific Reports 14 (1): 20807. Crossref

Saleh, F., Candela, Y., Harper, D.A.T., Polechová, M., Lefebvre, B., and Pittet, B. 2018. Storm-induced community dynamics in the Fezouata Biota (Lower Ordovician, Morocco). Palaios 33: 535–541. Crossref

Saleh, F., Lefebvre, B., Hunter, A.W., and Nohejlová, M. 2020. Fossil weathering and preparation mimic soft tissues in eocrinoid and somasteroid echinoderms from the Lower Ordovician of Morocco. Microscopy Today 28: 24–28. Crossref

Saleh, F., Lustri, L., Gueriau, P., Potin, G.J.-M., Pérez-Peris, F., Laibl, L., Jamart, V., Vite, A., Antcliffe, J.B., Daley, A.C., Nohejlová, M., Dupichaud, C., Schöder, S., Bérard, E., Lynch, S., Drage, H.B., Vaucher, R., Vidal, M., Monceret, E., Monceret, S., and Lefebvre, B. 2024b. The Cabrières Biota (France) provides insights into Ordovician polar ecosystems. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8: 1–12. Crossref

Saleh, F., Vaucher, R., Vidal, M., Hariri, K.E., Laibl, L., Daley, A.C., Gutiérrez-Marco, J.C., Candela, Y., Harper, D.A.T., and Ortega-Hernández, J. 2022. New fossil assemblages from the Early Ordovician Fezouata Biota. Scientific Reports 12 (1): 20773. Crossref

Saleh, F., Vidal, M., Laibl, L., Sansjofre, P., Gueriau, P., Pérez-Peris, F., Lustri, L., Lucas, V., Lefebvre, B., Pittet, B., El Hariri, K., and Daley, A.C. 2021. Large trilobites in a stress-free Early Ordovician environment. Geological Magazine 158: 261–270. Crossref

Savoca, M.S., Czapanskiy, M.F., Kahane-Rapport, S.R., Gough, W.T., Fahlbusch, J.A., Bierlich, K.C., Segre, P.S., Di Clemente, J., Penry, G.S., Wiley, D.N., Calambokidis, J., Nowacek, D.P., Johnston, D.W., Pyenson, N.D., Friedlaender, A.S., Hazen, E.L., and Goldbogen, J.A. 2021. Baleen whale prey consumption based on high-resolution foraging measurements. Nature 599: 85–90. Crossref

Schweitzer, C.E., Feldmann, R.M., Hu, S., Huang, J., Zhou, C., Zhang, Q., Wen, W., and Xie, T. 2014. Penaeoid Decapoda (Dendrobranchiata) from the Luoping biota (Middle Triassic) of China: systematics and taphonomic framework. Journal of Paleontology 88 : 457–474. Crossref

Servais, T., Owen, A.W., Harper, D.A.T., Kröger, B., and Munnecke, A. 2010. The great Ordovician biodiversification event (GOBE): the palaeoecological dimension. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 294: 99–119. Crossref

Servais, T., Perrier, V., Danelian, T., Klug, C., Martin, R., Munnecke, A., Nowak, H., Nützel, A., Vandenbroucke, T.R.A., Williams, M., and Rasmussen, C.M.Ø. 2016. The onset of the “Ordovician Plankton Revolution” in the late Cambrian. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 458: 12–28. Crossref

Smith, C.R., Glover, A.G., Treude, T., Higgs, N.D., and Amon, D.J. 2015. Whale-fall ecosystems: recent insights into ecology, paleoecology, and evolution. Annual Review of Marine Science 7: 571–596. Crossref

Stamhuis, E.J., Dauwe, B., and Videler, J.J. 1998. How to bite the dust: morphology, motion pattern and function of the feeding appendages of the deposit-feeding thalassinid shrimp Callianassa subterranea. Marine Biology 132: 43–58. Crossref

Steenstrup, J. 1857 . Oplysninger orn Atlanterhavets colossale Blaeksprutter. Forhandlinger ved de Skandinaviske Naturforskeres 7: 182–185.

Stobberup, K., Morato, T., Amorim, P., and Erzini, K. 2009. Predicting weight composition of fish diets: converting frequency of occurrence of prey to relative weight composition. The Open Fish Science Journal 2 : 42–49. Crossref

Sun, Z., Zeng, H., and Zhao, F. 2020. A new middle Cambrian radiodont from North China: implications for morphological disparity and spatial distribution of hurdiids. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 558: 109947. Crossref

Tucker, J.P., Vercoe, B., Santos, I.R., Dujmovic, M., and Butcher, P.A. 2019. Whale carcass scavenging by sharks. Global Ecology and Conservation 19: e00655. Crossref

Van Roy, P. and Briggs, D.E.G. 2011. A giant Ordovician anomalocaridid. Nature 473: 510–513. Crossref

Van Roy, P. and Tetlie, O.E. 2006. A spinose appendage fragment of a problematic arthropod from the Early Ordovician of Morocco. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51: 239–246.

Van Roy, P., Briggs, D.E.G., and Gaines, R.R. 2015a. The Fezouata fossils of Morocco; an extraordinary record of marine life in the Early Ordovician. Journal of the Geological Society 172: 541–549. Crossref

Van Roy, P., Daley, A.C., and Briggs, D.E.G. 2015b. Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. Nature 522: 77–80. Crossref

Van Roy, P., Orr, P.J., Botting, J.P., Muir, L.A., Vinther, J., Lefebvre, B., Hariri, K.e., and Briggs, D.E.G. 2010. Ordovician faunas of Burgess Shale type. Nature 465: 215–218. Crossref

Vannier, J., Vidal, M., Marchant, R., El Hariri, K., Kouraiss, K., Pittet, B., El Albani, A., Mazurier, A., and Martin, E. 2019. Collective behaviour in 480-million-year-old trilobite arthropods from Morocco. Scientific Reports 9 (1): 14941. Crossref

Vidal, M. 1998a. Le modèle des biofaciès à trilobites: un test dans l’Ordovicien inférieur de l’Anti-Atlas, Maroc. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences-Series IIA-Earth and Planetary Science 327: 327–333. Crossref

Vidal, M. 1998b. Trilobites (Asaphidae et Raphiophoridae) de l’Ordovician inférieur et l’Anti-Atlas, Maroc. Palaeontographica Abt. A 251: 39–77. Crossref

Walcott, C.D. 1908. Mount Stephen rocks and fossils. The Canadian Alpine Journal 1: 232–248.

Walcott, C.D. 1911. Cambrian Geology and Paleontology II: Middle Cambrian Holothurians and Medusae. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 57 (3): 41–69.

Walcott, C.D. 1912. Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita, and Merostomata. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 57 (6): 143–228.

Waterston, C.D. 1964. II.—Observations on Pterygotid Eurypterids. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 66 (2): 9–33. Crossref

Whittington, H.B. and Briggs, D.E.G. 1985. The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British-Columbia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences 309: 569–609. Crossref

Wu, Y., Fu, D., Ma, J., Lin, W., Sun, A., and Zhang, X. 2021. Houcaris gen. nov. from the early Cambrian (Stage 3) Chengjiang Lagerstätte expanded the palaeogeographical distribution of tamisiocaridids (Panarthropoda: Radiodonta). PalZ 95: 209–221. Crossref

Wu, Y., Pates, S., Liu, C., Zhang, M., Lin, W., Ma, J., Wu, Y., Chai, S., Zhang, X., and Fu, D. 2024a. A new radiodont from the lower Cambrian (Series 2 Stage 3) Chengjiang Lagerstätte, South China informs the evolution of feeding structures in radiodonts. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 22: 2364887. Crossref

Wu, Y., Pates, S., Pauly, D., Zhang, X., and Fu, D. 2024b. Rapid growth in a large Cambrian apex predator. National Science Review 11 : nwad284. Crossref

Wu, Y., Pates, S., Zhang, M., Lin, W., Ma, J., Liu, C., Wu, Y., Zhang, X., and Fu, D. 2024c. Exceptionally preserved radiodont arthropods from the lower Cambrian (Stage 3) Qingjiang Lagerstätte of Hubei, South China and the biogeographic and diversification patterns of radiodonts. Papers in Palaeontology 10: e1583. Crossref

Zhu, X., Lerosey-Aubril, R., and Ortega-Hernández, J. 2021. Furongian (Jiangshanian) occurrences of radiodonts in Poland and South China and the fossil record of the Hurdiidae. PeerJ 9: e11800. Crossref

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 709–722, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01278.2025