A new pycnodontid fish from a freshwater habitat in the Upper Cretaceous Iharkút vertebrate locality, Bakony Mountains, Hungary

MÁRTON SZABÓ and JOHN J. CAWLEY

Szabó, M. and Cawley, J.J. 2025. A new pycnodontid fish from a freshwater habitat in the Upper Cretaceous Iharkút vertebrate locality, Bakony Mountains, Hungary. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 70 (4): 765–773.

25 years ago, a diverse vertebrate assemblage was discovered at the famous Santonian (Upper Cretaceous) Iharkút fossil locality (Bakony Mts, western Hungary). Fishes, among them members of the order Pycnodontiformes have been important components of this continental ecosystem. Members of the order Pycnodontiformes have previously been reported from the Iharkút location by remains referred to as cf. Coelodus sp. Revision of the already published material and the elaboration of recently collected specimens have led to identification of a new pycnodontid species Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov., based on upper and lower jaw elements. The new species expands the geographical range of the genus Polazzodus, and largely contributes to our knowledge on the generic diversity of Late Cretaceous freshwater pycnodonts.

Key words: Pycnodontiformes, Pycnodontidae, Polazzodus, Santonian, Cretaceous, Iharkút, Hungary.

Márton Szabó [szabo.marton@nhmus.hu, martonszabo@staff.elte.hu, szabo.marton.pisces@gmail.com; ORCID: https:// orcid.org/0000-0002-3233-7797 ], Hungarian National Museum Public Collection Centre – Hungarian Natural History Museum, Department of Palaeontology and Geology, H-1083 Budapest, Ludovika tér. 2, Hungary; ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Department of Palaeontology, H-1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/C, Hungary.

John J. Cawley [johnjosephcawley@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3703-4138 ], Department of Palaeontology, University of Vienna, Josef-Holaubek-Platz 2, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Received 6 August 2025, accepted 16 September 2025, published online 11 December 2025.

Copyright © 2025 M. Szabó and J.J. Cawley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The order Pycnodontiformes (commonly referred to as “pycnodont fishes”) is an extinct group of neopterygians with nearly worldwide distribution (except Australia) and average body length of about 25 cm, while some species may even reach 200 cm in full body length (Poyato-Ariza 2003; Kriwet 2005). The order Pycnodontiformes has a temporal range from at least the Ladinian (late Middle Triassic) to the Priabonian (late Eocene) (Cooper and Martill 2020b; Capasso 2021a). During their nearly 200 million years long evolutionary history, they occupied a variety of important niches in marine, freshwater and brackish ecosystems (Kriwet 2001, 2005; Capasso 2021a; Cawley and Kriwet 2024). Members of the order Pycnodontiformes, with a few exceptions, are easily recognizable by their characteristic bauplan, which is characterized by the following: deep and laterally compressed (circular to quadrate) body, inequilateral fins, frontal flexure of the skull, more or less prognathous snout, reduced opercular series, and a specialized feeding apparatus (Kriwet 2001, 2005; Capasso 2021a, 2023). Diet of pycnodontiform fishes predominantly consisted of hard-shelled invertebrates, including crustaceans and echinoderms (Kriwet 2001; Capasso 2019, 2021a, b; Cooper and Martill 2020a, b), however, carnivorous (piscivorous) forms are also known in the fossil record (Vullo et al. 2017; Kölbl-Ebert et al. 2018; Capasso 2019, 2021a).

The Hungarian dinosaur locality Iharkút was discovered in the year 2000. It has now become one of the most important Upper Cretaceous vertebrate fossil localities in Europe, where remains of more than 40 vertebrate taxa, including fishes, amphibians, turtles, lizards, a freshwater mosasaur, pterosaurs, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and birds were discovered during the last 25 years of excavations (Ősi et al. 2012; Botfalvai et al. 2021). The Iharkút fish fauna, as it was known until the present study, is composed by a lepisosteid gar Atractosteus sp., a pycnodont identified as cf. Coelodus sp., a vidalamiin and a possibly non-vidalamiin Amiidae, an indeterminate elopiform and two indeterminate ellimmichthyiforms, a teleost referred to as cf. Salmoniformes indet., indeterminate acanthomorphs, at least one indeterminate teleostean, and numerous indeterminate actinopterygians (Szabó et al. 2016a, b; Szabó and Ősi 2017).

Our study describes the material referable to the new Polazzodus species in detail with two specimens formerly assigned to cf. Coelodus (Szabó et al. 2016b) and one specimen described for the first time. These findings emphasize our knowledge on the composition of the Iharkút vertebrate fauna, the paleoenvironmental inferences of the Iharkút ecosystem, and the palaeobiogeographical distribution of the genus Polazzodus.

Institutional abbreviations.— AK-PYC, Asfla pycnodonts accessioned in NHMUK (see Cooper and Martill 2020b); MPCM, Museo Paleontologico Cittadino di Monfalcone, Italy; NHMUK, Natural History Museum, London, UK; NHMUS, Hungarian National Museum Public Collection Centre – Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary.

Nomenclatural acts.—This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in Zoobank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F59E1B55-CF20-4DB0-B597-EE737C186DEB.

Geological setting

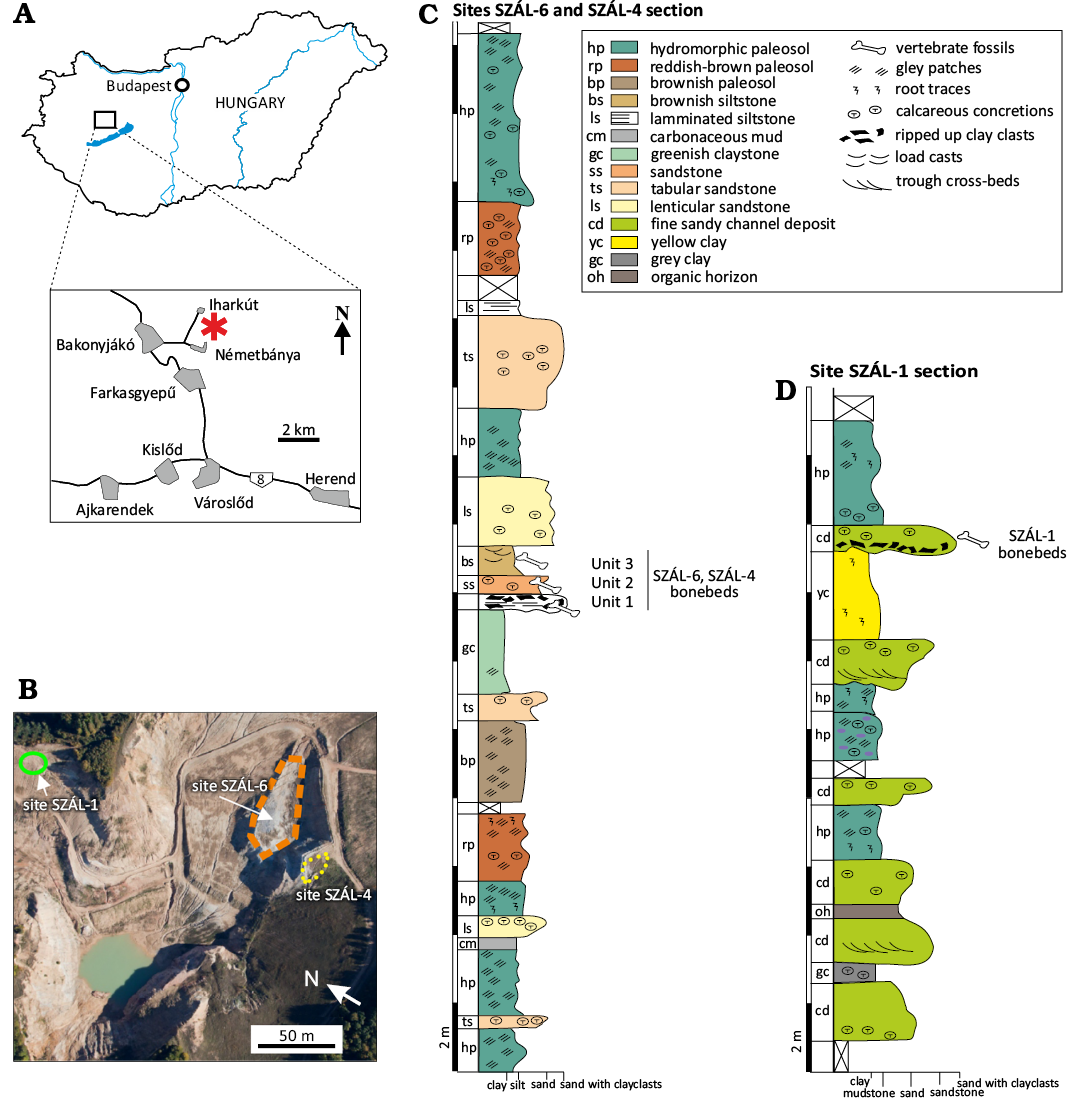

The locality is in an abandoned open-pit bauxite mine near the villages of Németbánya and Bakonyjákó, in the area of the former village Iharkút (Fig. 1A).

The Iharkút open-pit bauxite mine is located in the Transdanubian Central Range, a tectonic block situated on the northern part of the triangular-shaped Apulian microplate between Africa and Europe during the Mesozoic (Csontos and Vörös 2004; Csiki-Sava et al. 2015). The bedrocks of the Iharkút locality belong to the Upper Triassic Main Dolomite Formation. In this formation, tectonically controlled and karstified sinkholes (with depths of 50–90 m) were infilled by the Upper Cretaceous (pre-Santonian) Nagytárkány Bauxite Formation (this bauxite was mined in the area from the 1970’s). At the Iharkút vertebrate locality, the red bauxite ore, together with the karstified paleosurface of Triassic rocks, was covered by a sequence of alluvial flood plain deposits of the Csehbánya Formation in 50 m thickness.

At the locality, this formation is composed of alternating coarse basal breccia, sandstone, siltstone, and paleosol beds (Jocha-Edelényi 1988; Ősi and Mindszenty 2009; Botfalvai et al. 2015). The observable sedimentary structures (Botfalvai et al. 2016) and the revealed mollusc (Szentesi 2008; Ősi 2012; István Szente personal communication 2014) and ostracod fauna (Miklós Monostori personal communcation 2003) indicate a freshwater environment during the deposition of the Csehbánya Formation. Based on the results of palynological investigations, a Santonian age has been attributed to the formation (Bodor and Baranyi 2012).

Fig. 1. A. Location map of the Iharkút vertebrate locality (asterisk). B. Aerial photo of the Iharkút open-pit, showing the position of the SZÁL-1, SZÁL-4, and SZÁL-6 sites. C. Stratigraphic section of the SZÁL-4 and SZÁL-6 sites. D. Stratigraphic section of the SZÁL-1 site (modified after Botfalvai et al. 2015).

Various stratigraphic horizons of the bone-yielding beds of the Csehbánya Formation produced rich and diverse fossil assemblage (Fig. 1B). Concerning the pycnodontiform fossils, the so-called SZÁL-6 and SZÁL-4 sites (which are the most productive sequence at the entire Iharkút locality) are composed of a greyish coarse basal breccia covered with sandstone and brownish siltstone (Fig. 1C). The stratigraphic built-up of these, closely situated sections are basically the same, however, they are separated from each other by a fault. In addition, the SZÁL-1 site is also worth mentioning (Fig. 1D), since an important pycnodontiform prearticular has been discovered there.

Material and methods

The hereby introduced Iharkút specimens were discovered after a thorough revision of the local pycnodont remains discovered between 2016 and 2025. The remains were collected at three different sites of the Iharkút locality, namely the SZÁL-1, SZÁL-4, and the SZÁL-6 sites (see above), during the annual excavations between the years 2010–2023. The hereby introduced, new pycnodont remains are brownish, greyish and black in color. All of the Iharkút pycnodont fossils are isolated remains, neither associable elements, nor complete or partial skeletons have been found so far.

All Iharkút specimens are housed in the Hungarian National Museum Public Collection Centre – Hungarian Natural History Museum (NHMUS), where they were cleaned and prepared mechanically in the technical lab of the Department of Paleontology and Geology. Needles and vibrotool were used for mechanical preparation. In order to stop (or at least slow down) the oxidization of the high pyrite content of the fossils, they were treated with polyvinyl butyral (PVB). Broken bone elements were repaired with cyanoacrylate (superglue).

Systematic palaeontology

Class Osteichthyes Huxley, 1880

Subclass Actinopterygii Cope, 1887

Series Neopterygii Regan, 1923

Order Pycnodontiformes Berg, 1937

Family Pycnodontidae sensu Nursall, 1996

Genus Polazzodus Poyato-Ariza, 2010

Type species: Polazzodus coronatus Poyato-Ariza, 2010; Polazzo, Italy, Santonian, Upper Cretaceous.

Species included: Polazzodus coronatus Poyato-Ariza, 2010; Polazzodus gridellii d’Erasmo, 1952, and Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. (see below).

Diagnosis (after Poyato-Ariza 2010).—Second dorsal ridge scale with anterior projection and concave anterior border; presence of olfactory fenestra on premaxilla; maxilla with axe blade morphology; presence of conspicuous posterodorsal process on cleithrum; cloaca formed by bifid scale plus flanking scales thin, short, and straight.

Remarks.—The genus Polazzodus, with the type species Polazzodus coronatus was originally described from the lower Santonian (Upper Cretaceous) of Polazzo, northeastern Italy based on numerous specimens, many of which are very well-preserved (Poyato-Ariza 2010). Polazzodus gridellii (originally described as “Coelodus” gridellii) was described after three small specimens from Polazzo, Italy, of which only one has survived the last decades (Poyato-Ariza 2020). Since the outcrop from where the specimens of P. gridellii originate was destroyed during World War I, the precise provenance and age of the fossils are unknown. However, similar outcrops in the nearby area are considered to be lower Santonian (Upper Cretaceous) in age (Poyato-Ariza 2020). An isolated vomerine dentition found in the Turonian (Upper Cretaceous) of Asfla, Morocco has been identified as Polazzodus sp. (Cooper and Martill 2020a). Another isolated vomerine dentition from the Albian–Cenomanian of Mrzlek near Solkan (Slovenia) was referred to as cf. Polazzodus sp. (Križnar 2014).

Geographic and stratigraphic range.—Polazzo (Italy) and Iharkút (Hungary), and possibly also Mrzlek (Slovenia) and Asfla (Morocco); Albian–Cenomanian (Lower–Upper Cretaceous), Turonian, and Santonian (Upper Cretaceous).

Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov.

Figs. 2, 3.

Zoobank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:4E9E1C59-576E-46F3-AE67-FE365E364629.

2016 cf. Coelodus sp.; Szabó et al. 2016b: 126–128, figs. 3D, 4D.

Etymology: In honour of László Mihályfi, high school biology teacher of both Márton Szabó and Attila Ősi (head of the Iharkút Research Group).

Type material: Holotype, one vomer (NHMUS PAL 2025.26.1.). Paratypes: two right prearticulars (NHMUS PAL 2025.27.1., 2025.28.1.). No further specimens are known.

Type locality: SZÁL-4 site, abandoned open-pit bauxite mine at Iharkút, Bakony Mts, western Hungary (see Fig. 1).

Type horizon: Csehbánya Formation, Santonian, Upper Cretaceous.

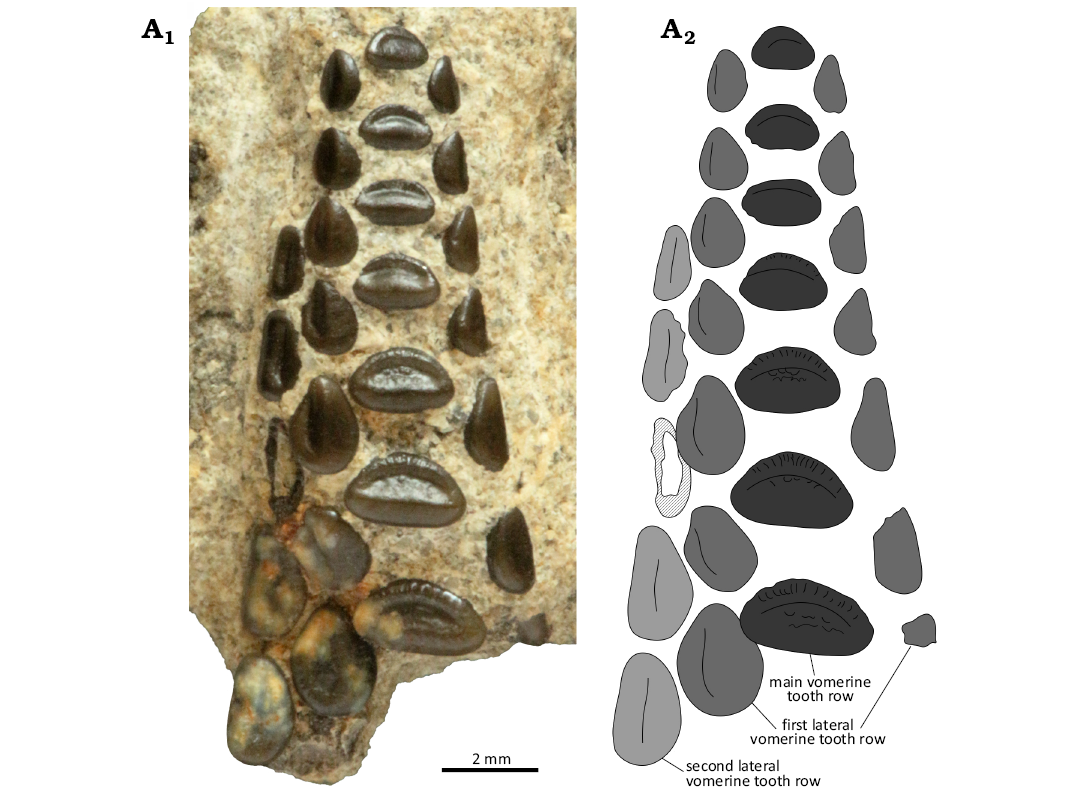

Diagnosis.—Pycnodontid pycnodontiform fish with the following combination of jaw and tooth characters: anterior-posteriorly slender vomerine, teeth of the main vomerine tooth row subcircular to moderately triangular (with rounded edges) in occlusal view with a central groove surrounded by crenulations, visually large gaps (diastemas) between teeth of the main vomerine tooth row, teeth of the first lateral vomerine tooth row teardrop-shaped with large medial, anteroposteriorly running ridge, teeth of the secondary lateral vomerine tooth row subtriangular to oval and elongated parallelly to the longitudinal axis of the vomer; prearticulars with three distinct rows of teeth (irregular, small, circular prearticular teeth can occur), prearticular teeth with large central groove surrounded by gentle crenulations.

Description.—The only vomerine toothplate (NHMUS PAL 2025.26.1., holotype; anterio-posterior length: 15.4 mm) has four tooth rows preserved in total, these are the main row, the two right lateral rows and the first left lateral row (Fig. 2). Each tooth row has teeth increasing in size towards the posterior end. A central groove surrounded by gentle crenulations can be observed on unworn teeth. The main vomerine tooth row has seven teeth with the most anterior tooth being sub-oval in shape while the remaining teeth are subtriangular with rounded edges. A diastema is present between each tooth on the main vomerine tooth row. Seven teeth are present on the first lateral vomerine tooth rows on either side of the main vomerine tooth row. The teeth on the first lateral row are teardrop-like in shape with medial ridges on the occlusal surface. These ridges are also present on the first lateral row to the right of the main tooth row as the portion of the teeth underneath the overhanging ridges appear to be concealed within the matrix. The secondary lateral vomerine tooth row has five teeth preserved with the most anterior being subtriangular and the most posterior being subreniform in shape. All teeth on the lateral rows are elongated parallel to the longitudinal axis of the vomer.

Fig. 2. Pycnodontid fish Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. (holotype, NHMUS PAL 2025.26.1.) from the Santonian (Upper Cretaceous), SZÁL-4 site, Iharkút, Bakony Mts, western Hungary. Photograph (A1) and line drawing (A2) of vomer in occlusal view.

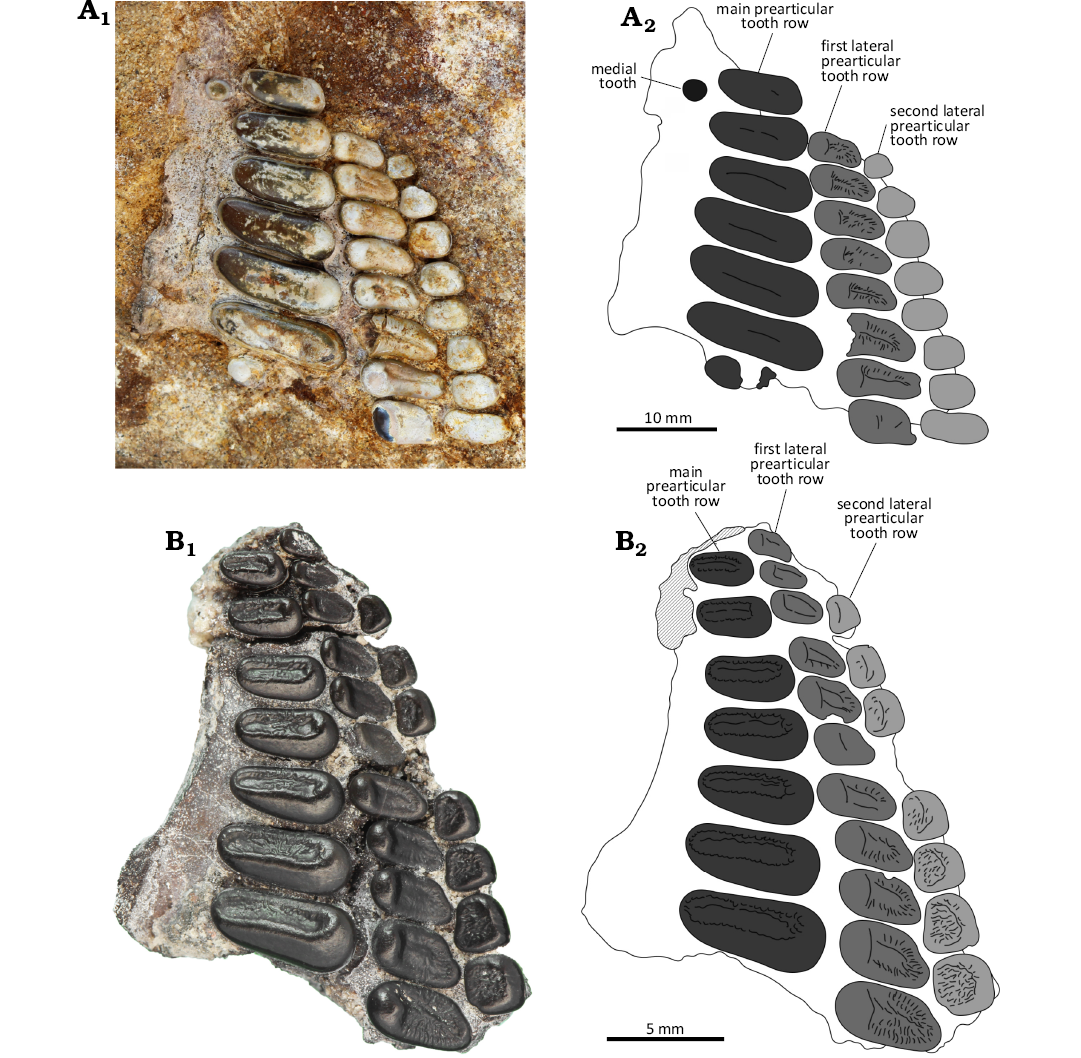

Both prearticulars have three distinct rows of teeth. Unworn teeth, like those of the vomerine toothplate, have a central groove with marginal crenulations.

NHMUS PAL 2025.27.1. (Fig. 3A, B) is the larger of the two, being 43.7 mm of anterio-posterior length. One small rounded tooth is present medial to the most anterior tooth of the main tooth row. These irregular small teeth are also seen in specimens of Polazzodus coronatus (Poyato-Ariza 2010) and can be commonly observed across Pycnodontiformes (Longbottom 1984; Capasso 2021b; Collins and Underwood 2021). The main prearticular tooth row consists of seven elongated oval shaped teeth with the most posterior tooth being partially visible from within the rocky matrix. The eight teeth sitting in the first lateral prearticular tooth row are less elongated but still oval in shape. The first eight teeth of the secondary lateral prearticular tooth row are subcircular and subtriangular in form, while the posteriormost tooth of this row is oval shaped.

The prearticular NHMUS PAL 2025.28.1. (Fig. 3C, D; anterio-posterior length: 22.9 mm) also has seven oval shaped teeth in the main prearticular tooth row while possessing eleven oval teeth in the first lateral prearticular tooth row. The grooves on the first lateral prearticular teeth are especially conspicious with the lingually facing side of the tooth having a higher elevation than the rest of the tooth with a convex protuberance overhanging the central groove. The secondary lateral prearticular tooth row has seven preserved teeth which are mostly subtriangular in shape with the posteriormost tooth having a subcircular form in occlusal view.

Fig. 3. Pycnodontid fish Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. (paratypes) from the Santonian (Upper Cretaceous), Iharkút, Bakony Mts, western Hungary. A. NHMUS PAL 2025.27.1., SZÁL-1 site. B. NHMUS PAL 2025.28.1., SZÁL-6 site. Photographs (A1, B1) and line drawings (A2, B2) of right prearticular in occlusal view.

Remarks.—The specimens described herein are assigned to Polazzodus due to the similarity of several characters of the vomerine and prearticular tooth plates to the holotype of the species of Polazzodus coronatus (Poyato-Ariza 2010), alongside similarities in the characters of the vomerine toothplates with Polazzodus sp. from the Turonian Akrabou Formation of Asfla in Morocco (Cooper and Martill 2020b) and cf. Polazzodus sp. from Mrzlek, Slovenia (Križnar 2014). The only remaining specimen of Polazzodus gridellii does not have the jaw apparatus preserved (see Poyato-Ariza 2020: fig. 1), therefore it is hereby not compared to our material.

The hereby described vomer of Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. differs from the vomers of Polazzodus coronatus (Poyato-Ariza 2010) from the Santonian of Polazzo, and from that of Polazzodus sp. from the Turonian Akrabou Formation of Asfla in Morocco (Cooper and Martill 2020b) in only having four tooth rows preserved in contrast to the five seen in the aforementioned specimens. This is due to the preservation bias as the tooth morphology of the main tooth row and the lateral tooth rows are similar to that seen in previously published P. coronatus, Polazzodus sp. and cf. Polazzodus sp. (Poyato-Ariza 2010; Križnar 2014; Cooper and Martill 2020b).

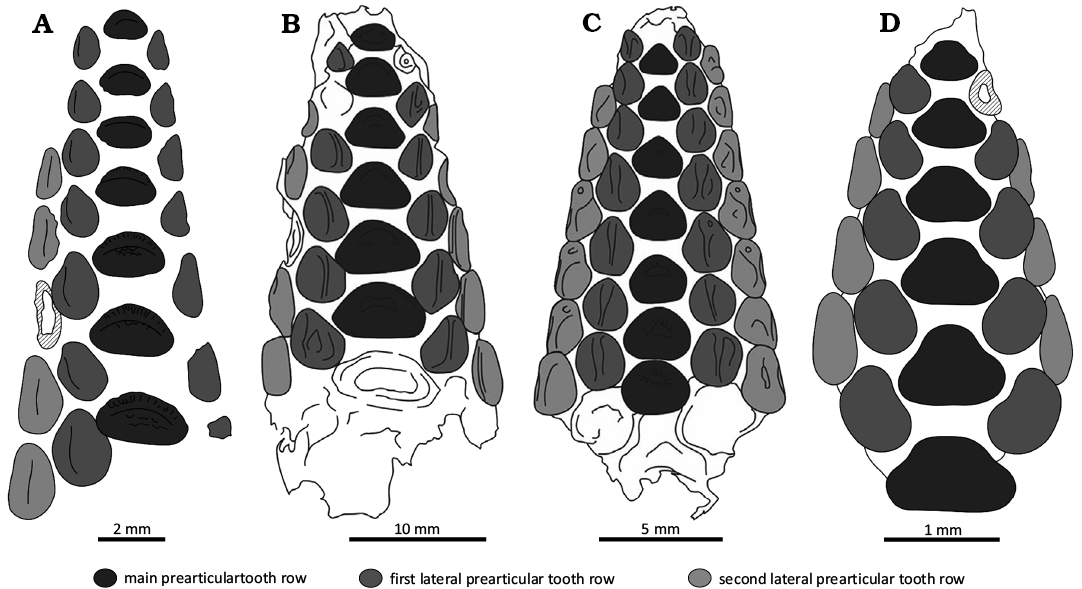

The main tooth row of NHMUS PAL 2025.26.1. differs from the Italian P. coronatus in having less distinctively triangular teeth and being more dorso-ventrally compressed in occlusal view. The teeth in the main vomerine tooth row are also less equilateral than those of the Turonian Polazzodus sp. from the Akrabou Formation in Asfla, Morocco (AK-PYC 5; Cooper and Martill 2020b). All known vomers seen in P. coronatus and Polazzodus sp. specimens have a maximum number of seven teeth in the main vomerine tooth row with the exception of cf. Polazzodus sp. from Mrzlek, Slovenia (Križnar 2014) which has six teeth in the main vomerine tooth row (though this could be the result of intraspecific variation or preservation bias). However, due to the size (6–7 mm) and age (Albian–Cenomanian) of the Mrzlek vomer, it likely represents a different species than the Iharkút species P. mihalyfii sp. nov. The teeth in the main vomerine tooth row of the cf. Polazzodus sp. from Mrzlek specimen are also more strongly triangular in form compared to those in the vomer of P. mihalyfii sp. nov. from Iharkút. The tooth numbers in the lateral rows of the Mrzlek specimen are also reduced compared to those of the other Polazzodus specimens (first lateral row: five; second lateral row: four). Compared to othe other species, the diastemas between the teeth of the main vomerine tooth row and the marginal crenulations of the vomerine teeth are more pronounced in P. mihalyfii sp. nov. For a visual summary of the above listed differences in the published Polazzodus vomers, see Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Comparison of vomers assigned to species of Polazzodus. A. Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. (Santonian, Hungary). B. Polazzodus coronatus (Santonian, Italy). C. Polazzodus sp. (Turonian, Morocco). D. cf. Polazzodus sp. (Albian–Cenomanian, Slovenia). Modified after Poyato-Ariza (2010, 2020), Križnar (2014), and Cooper and Martill (2020b).

Prearticulars of Polazzodus are known only from the P. coronatus from Polazzo (Poyato-Ariza 2010) and will serve as the sole basis of comparison. While the teeth on two P. coronatus specimens (MPCM 11360, MPCM 10879; see Poyato-Ariza 2010: fig. 5E, F) are far more worn than those of the Iharkút specimens with no ornamentations, the central groove and crenulations can still be observed in MPCM 12264 and MPCM 11333 (Poyato-Ariza 2010: fig. 5A–C). Polazzodus coronatus specimens share the general tooth morphology of the P. mihalyfii sp. nov. with MPCM 10879 also showcasing the subcircular/subtriangular morphology present in the second lateral prearticular tooth row. Another observation that can be made is that the teeth in the lateral prearticular rows become more elongate during ontogeny, particularly the more posterior teeth of the secondary lateral prearticular row which can be seen in MPCM 10879. This can also be observed in P. mihalyfii sp. nov. as the first lateral prearticular teeth in NHMUS PAL 2025.27.1. are larger than those seen in NHMUS PAL 2025.28.1. Also the two posteriormost teeth of the second lateral prearticular row in NHMUS PAL 2025.27.1. are more elongate than the subcircular/subtriangular teeth seen in NHMUS PAL 2025.28.1. Polazzodus coronatus also possess this trend in tooth morphology through ontogeny as the oval teeth of the main and first lateral prearticular row of MPCM 10879 are more elongate than those of MPCM 11333. Additionally, the tooth morphology of the second lateral prearticular tooth row in the P. mihalyfii sp. nov. NHMUS PAL 2025.28.1. is more similar to that seen in the P. coronatus MPCM 11333 where the most posterior teeth are not as elongate as seen in larger specimens such as the MPCM 10879 (P. coronatus) or the Iharkút NHMUS PAL 2025.27.1. (P. mihalyfii sp. nov.).

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Iharkút (Hungary); Santonian (Upper Cretaceous).

Discussion

The discovery of Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. in the Santonian (Upper Cretaceous) of Iharkút extends the palaeobiogeographical distribution of the genus Polazzodus, but it fits into the established Late Cretaceous temporal range of the genus (Poyato-Ariza 2010, 2020; Križnar 2014; Cooper and Martill 2020b).

Concerning the paleoenvironment of the type material of Polazzodus coronatus, the locality of Polazzo is part of a very large marine carbonate platform with rudist reefs forming internal shallow lagoons (Tintori et al. 1993; Dalla Vecchia et al. 2001). The Moroccan Polazzodus sp. vomerine dentition originates from the Asfla Member of the Akrabou Formation, which is is a prograding marine carbonate sequence (Ettachfini and Andreu 2004). The palaeoenvironment of Mrzlek, from where cf. Polazzodus sp. originates (Križnar 2014), is still little known as deciphering its sedimentology has been problematic (Tyler and Križnar 2013) and as such, comparison of this locality with other palaeoenvironments in this discussion is premature. In contrast, the Csehbánya Formation outcropping at Iharkút was deposited in an anastomozing fluvial system, and is therefore of freshwater origin (Botfalvai et al. 2016). This is therefore, the first known occurence of Polazzodus in a freshwater environment. The freshwater status of the Csehbánya Formation is also supported by the fact that when pycnodont teeth from Iharkút were tested for strontium concentrations, they were found to be far below what is expected of marine vertebrates (>1000 ppm) (Kocsis et al. 2009). Additionally, the specimens described here originate from the same horizon (SZÁL-6) as Pannoniasaurus inexpectatus (Makádi et al. 2006, 2012) a mosasaur that was also tested for strontium concentrations (Kocsis et al. 2009) and had similar values to the pycnodonts suggesting that both taxa inhabited freshwater environment. This along with the specimens having a wide range of sizes representing different ontogenetic stages is strong evidence towards P. mihalyfii sp. nov. having been a permanent freshwater resident.

According to Poyato-Ariza (2010), P. coronatus was a small (97 mm maximum standard length) and low-bodied pycnodont. The snout is elongate and gently downturned with a shallow caudal region creating an overall truncated lateral outline. A similar morphology is observable in some extant fish groups (i.e., butterflyfishes, family Chaetodontidae). These fishes use their elongated rostrum to forage on small prey items, hidden within narrow crevasses and burrows in hard bottom substrates (Cooper and Martill 2020b). P. mihalyfii sp. nov. likely occupied a similar niche within the Iharkút vertebrate assemblage, feeding on smaller and/or softer shelled prey items like small crustaceans (e.g., ostracods) or small sized gastropods (i.e., Hadraxon cf. csingervallense, Parateinostoma sp., Czabalaya? sp., Auriculinella sp.; see Szentesi 2008), which were perhaps inaccessible for larger durophagous fishes present in the assemblage, i.e., the other pycnodontid present in Iharkút which has been identified as cf. Coelodus sp. (with an estimated standard length of 270 mm; Szabó et al. 2025: fig. 5). These specimens are distinguished from P. mihalyfii sp. nov. based on tooth morphology and ornamentation on the prearticulars being closer to those diagnostic of Coelodus than any other genus. For an artistic reconstruction of the Iharkút pycnodont fishes see Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Artistic depiction of the Iharkút pycnodonts, Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. (below) and cf. Coelodus sp. (above). Paleoart by Márton Szabó.

Conclusions

We describe Polazzodus mihalyfii sp. nov. from a Santonian (Late Cretaceous) freshwater environment based on upper and lower jaw elements found at Iharkút (Bakony Mts, Hungary). While it is of an age similar to that of the type species of the genus, Polazzodus coronatus, it differs from it in possessing dorso-ventrally compressed subtriangular teeth with rounded edges and wide diastemas in the main tooth row of the vomer. Another major difference is that P. coronatus occupied shallow marine reefs while P. mihalyfii sp. nov. most likely has been a fully freshwater form due to previous analysis of strontium concentrations. Moreover, the wide size range of the here referred remains indicates that these fishes permanently inhabited freshwater habitats of Iharkút during the Santonian. Other, much larger pycnodonts are already documented from the Iharkút site (Szabó et al. 2016b, 2025), however, due to the elongated snout typical of Polazzodus which could have enabled crevice feeding, the Iharkút pycnodonts likely occupied different niches. The presence of a freshwater pycnodont in the Iharkút ichthyofauna further strengthens the proposed freshwater dominance of the fish fauna of Iharkút during the Santonian. The new record of Polazzodus at Iharkút not only further contributes to the pycnodont fossil record of Hungary but it further adds to the diversity of known pycnodont genera that have adapted to freshwater environments during the Late Cretaceous. The revision of historical vertebrate fossil materials highlights the importance of museum collections to further document Mesozoic palaeo-biodiversity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Samuel Cooper (Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany) and Jürgen Kriwet (University of Vienna, Austria), whose constructive comments greatly improved an earlier version of the manuscript. Special thanks go to Gábor Botfalvai (Eötvös University, Budapest, Hungary) for his generous help regarding the stratigraphy of the Iharkút fossil locality. All members of the Iharkút Research Group and the 2010–2023 field crews are also acknowledged for their assistance in the fieldworks. Field and laboratory work was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH K 131597). NHMUS is hereby acknowledged for all technical support.

Editor: Camila Cupello

References

Berg, L.S. 1937. A classification of fish-like vertebrates. Bulletin de l’Académie des Sciences de l’USSR, Classe des Science mathématiques et naturelles 4: 1277–1280.

Bodor, E.R. and Baranyi, V. 2012. Palynomorphs of the Normapolles group and related plant mesofossils from the Iharkút vertebrate site, Bakony Mountains (Hungary). Central European Geology 55: 259–292. Crossref

Botfalvai, G., Haas, J., Bodor, E.R., Mindszenty, A., and Ősi, A. 2016. Facies architecture and palaeoenvironmental implications of the upper Cretaceous (Santonian) Csehbánya formation at the Iharkút vertebrate locality (Bakony Mountains, Northwestern Hungary). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 441: 659–678. Crossref

Botfalvai, G., Makádi, L., Albert, G., and Ősi, A. 2021. A Unique Late Cretaceous Dinosaur Locality in the Bakony-Balaton Geopark of Hungary (Iharkút, Bakony Mts.). Geoconservation Research 4: 459–470.

Botfalvai, G., Ősi, A., and Mindszenty, A. 2015. Taphonomic and paleoecologic investigations of the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Iharkút vertebrate assemblage (Bakony Mts, Northwestern Hungary). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 417: 379–405. Crossref

Capasso, L. 2019. Anomoeodus (Neopterygii, Pycnodontiformes) in the Turonian Marly Limestones of the ‘Azilé Series’ of the surroundings of Owendo, Gabon. Thalassia Salentina 41: 11–22.

Capasso, L. 2021a. Pycnodonts: an overview and new insights in the Pycnodontomorpha Nursall, 2010. Occasional Papers of the University Museum of Chieti, Monographic Publication 1: 1–223.

Capasso, L. 2021b. Pycnodonts were polyphyodont animals. Thalassia Salentina 43: 53–70.

Capasso, L. 2023. Biodiversity of †pycnodonts (Actinopterygii) during the Cenomanian–Turonian (Upper Cretaceous). Historical Biology 36: 1557–1569. Crossref

Cawley, J.J. and Kriwet, J. 2024. The fossil record and diversity of pycnodontiform fishes in non-marine environments. Diversity 16 (4): 225. Crossref

Collins, S.E. and Underwood, C.J. 2021. Unique damage‐related, gap‐filling tooth replacement in pycnodont fishes. Palaeontology 64 (4): 489504. Crossref

Cooper, S.L.A. and Martill, D.M. 2020a. A diverse assemblage of pycnodont fishes (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontiformes) from the mid-Cretaceous, continental Kem Kem Group of south-east Morocco. Cretaceous Research 112: 104456. Crossref

Cooper, S.L.A. and Martill, D.M. 2020b. Pycnodont fishes (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontiformes) from the Upper Cretaceous (lower Turonian) Akrabou Formation of Asfla, Morocco. Cretaceous Research 116: 104607. Crossref

Cope, E.D. 1887. Zittel’s manual of Palaeontology. American Naturalist 21: 1014–1019. Crossref

Csiki-Sava, Z., Buffetaut, E.,Ősi, A., Pereda-Suberbiola, X., and Brusatte, S.L. 2015. Island life in the Cretaceous—faunal composition, biogeography, evolution, and extinction of land-living vertebrates on the Late Cretaceous European archipelago. ZooKeys 469: 1–161. Crossref

Csontos, L. and Vörös, A. 2004. Mesozoic plate tectonic reconstruction of the Carpathian region. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 210: 1–56. Crossref

D’Erasmo, G. 1952. Nuovi ittiolitti cretacei del Carso Triestino. Atti del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Trieste 18: 81–122.

Dalla Vecchia, F.M., Rigo, D., Tentor, M., Pacor, G., and Moratto, D. 2001. Il sito paleontologico di Polazzo (Gorizia): dati e prospettive. In: M.C. Perri (ed.), Giornate di Paleontologia 2001. Giornale di Geologia, Serie 3 62 (for 2000) (Supplement): 151–156.

Ettachfini, M. and Andreu, B. 2004. Le Cenomanien et le Turonien de la Plateforme Preafricaine du Maroc. Cretaceous Research 25: 277–302. Crossref

Huxley, T.H. 1880. On the applications of the laws of evolution to the arrangements of the Vertebrata and more particularly of the Mammalia. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1880: 649–662.

Jocha-Edelényi, E. 1988. History of evolution of the Upper Cretaceous Basin in the Bakony Mts at the time of the terrestrial Csehbánya Formation. Acta Geologica Hungarica 31: 19–31.

Kocsis, L., Ősi, A., Vennemann, T., Trueman, C.N., and Palmer, M.R. 2009. Geochemical study of vertebrate fossils from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) Csehbánya Formation (Hungary): Evidence for a freshwater habitat of mosasaurs and pycnodont fish. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 280: 532–542. Crossref

Kölbl-Ebert, M., Ebert, M., Bellward, D.R., and Schulbert, C. 2018. A piranha-like pycnodontiform fish from the Late Jurassic. Current Biology 28: 3516–3521. Crossref

Kriwet, J. 2001. Palaeobiogeography of pycnodont fishes (Actinopterygii, Neopterygii). Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 5: 121–130.

Kriwet, J. 2005. A comprehensive study of the skull and dentition of pycnodont fishes. Zitteliana 45: 135–188.

Križnar, M. 2014. Ostanki zob piknodontnih rib (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontidae) iz krednih plasti Mrzleka pri Solkanu (Slovenija). RMZ—Materials and Geoenvironment 61: 183–189.

Longbottom, A.E. 1984. New Tertiary pycnodonts from the Tilemsi valley, Republic of Malawi. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Geology 38: 1–26.

Makádi, L., Botfalvai, G., and Ősi, A. 2006. The Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate fauna from the Bakony Mountains I: fishes, amphibians, turtles, squamates. Földtani Közlöny 136: 487–502.

Makádi, L., Caldwell, M.W., and Ősi, A. 2012. The First Freshwater Mosasauroid (Upper Cretaceous, Hungary) and a New Clade of Basal Mosasauroids. PloS ONE 7 (12): e51781. Crossref

Nursall, J.R. 1996. The phylogeny of pycnodont fishes. In: G. Arratia and G. Viohl (eds.), Mesozoic Fishes: Systematics and Paleoecology, 125–152. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München.

Ősi, A. 2012. Dinoszauruszok Magyarországon. 168 pp. GeoLitera Kiadó, Szeged.

Ősi, A. and Mindszenty, A. 2009. Iharkút, Dinosaur-bearing alluvial complex of the Csehbánya Formation. In: Cretaceous Sediments of the Transdanubian, Range, Fieldguide of the Geological Excursion Organized by the Sedimentological Subcommission of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Hungarian Geological Society, 51–63. Hungarian Geological Society, Budapest,

Ősi, A., Makádi, L., Rabi, M., Szentesi, Z., Botfalvai, G., and Gulyás, P. 2012. The Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate fauna from Iharkút, western Hungary: a review. In: P. Godefroit (ed.), Bernissart Dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems, 533–568. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Poyato-Ariza, F.J. 2003. Dental characters and phylogeny of pycnodontiform fishes. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23: 937–940. Crossref

Poyato-Ariza, F.J. 2010. Polazzodus, gen. nov., a new pycnodont fish from the Late Cretaceous of northeastern Italy. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30: 650–664. Crossref

Poyato-Ariza, F.J. 2020. Studies on pycnodont fihes (II): Revision of the subfamily Pycnodontinae, with special reference to Italian forms. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 126: 447–473.

Regan, C.T. 1923. The skeleton of Lepidosteus, with remarks on the origin and evolution of the lower neopterygian fishes. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1923: 445–461. Crossref

Szabó, M. and Ősi, A. 2017. The continental fish fauna of the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Iharkút locality (Bakony Mountains, Hungary). Central European Geology 60: 230–287. Crossref

Szabó, M., Gulyás, P., and Ősi, A. 2016a. Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Atractosteus (Actinopterygii, Lepisosteidae) remains from Hungary (Iharkút, Bakony Mountains). Cretaceous Research 60: 239–252. Crossref

Szabó, M., Gulyás, P., and Ősi, A. 2016b. Late Cretaceous (Santonian) pycnodontid (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontidae) remains from the freshwater deposits of the Csehbánya Formation (Iharkút, Bakony Mountains, Hungary). Annales de Paléontologie 102: 123–134. Crossref

Szabó, M., Haas, J., and Cawley, J.J. 2025. Pycnodontid remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Sümeg (western Hungary), with comments on the size of pycnodonts and a summary of the complete fossil record of the order Pycnodontiformes in Hungary. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen 315: 143–155. Crossref

Szentesi, Z. 2008. Az iharkúti késő-kréta kétéltű fauna vizsgálata. 74 pp. Unpublished M.Sc. Thesis, Eötvös Loránd University, Department of Paleontology, Budapest.

Tintori, A., Pugliese, N., and Calligaris, R. 1993. The Polazzo Locality. In: A. Tintori and G. Muscio (eds.), Fossil Fish Localities of Northern Italy —Field Guide Book. Mesozoic Fishes: Systematics and Paleoecology (Eichstätt, August 1993). Field trip: Northern Italy, August 13–17, 1993, 17–18.

Tyler, J.C. and Križnar, M. 2013. A new genus and species, Slovenitriacanthus saksidai, from southwestern Slovenia, of the Upper Cretaceous basal tetraodontiform fish family Cretatriacanthidae (Plectocretacicoidea). Bollettino del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona 37: 45–56.

Vullo, R., Cavin, L., Khalloufi, B., Amaghzaz, M., Bardet, N., Jalil, N.-E., Jourani, E., Khaldoune, F., and Gheerbrant, E. 2017. A unique Cretaceous–Paleogene lineage of piranha-jawed pycnodont fishes. Scientific Reports 7 (1): 6802. Crossref

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 70 (4): 765–773, 2025

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01279.2025